By Jennifer Kelly

In a bygone era, the measuring stick was the pounds a horse carried: a jockey, a saddle, and then whatever extra a racing secretary thought necessary to make the playing field equal. Weight-for-age scales and races said that a three-year-old should carry less weight than an older horse and that a filly at any age should carry less than her male peers. The goal was to give every horse in the field a fair shot at the finish line. Win often, carry more. Out of the money? Less for you! No surprise then that the greats carried the most: Man o’ War carried 138 pounds in the Potomac Handicap, Exterminator won the Kentucky Handicap with 137 pounds, and Kelso lugged 136 to win the Brooklyn Handicap and the Handicap Triple Crown. But to carry those imposts consistently and still win time after time? That takes a special horse.

A special horse named Forego.

A Titan on Stilts

To make a titan, a breeder needs to start with a king: Forli had been considered the “Argentinian Horse of the Century,” going undefeated at two and three in his native country. With Hyperion, winner of the Epsom Derby and the St. Leger Stakes, as his grandsire, he combined a desirable pedigree with obvious speed and stamina, a combination that saw Claiborne Farm pay $960,000 to bring Forli to the United States. Injured in his second American start, Forli spent his stud career at Claiborne, where he sired sixty stakes winners from 679 foals. Those included a bruising colt out of Lady Golconda, owned by Martha Gerry and Lazy F Ranch.

Martha Farish Gerry got her start in racing after her father’s sudden death in 1942. William Stamps Farish had started Lazy F Ranch outside of Houston, Texas, and had gotten into the racing game late in life, buying his first yearlings just before he passed away. Martha took over the ranch and the racing, turning her father’s initial investment into nearly six decades of owning and breeding. In 1969, she sent her mare Lady Golconda to Forli, and, on April 30, 1970, Lady Golconda foaled a large and mostly plain bay colt that Gerry named Forego.

As a yearling, he was big and rangy, with a large head and hindquarters that presaged his eventual height of seventeen hands. Gerry opted to geld Forego to tone down the attitude that made him difficult to handle and to slow down the growth that could exacerbate the one physical issue that plagued him throughout his career: his ankles. Forego often raced on a left front ankle that was never completely sound and a right hind ankle that swelled frequently. Gerry and trainer Sherrill Ward opted to delay Forego’s debut until his three-year-old season.

At three, he won three of his first seven starts before he started in the 1973 Kentucky Derby, where he finished fourth behind Secretariat. After that, he would go on to win the Discovery and Roamer Handicaps at three; the Brooklyn Handicap, the Woodward Stakes, and the Jockey Club Gold Cup at four; and then the Brooklyn and the Woodward again at age five, adding the Suburban to his list of Handicap Triple Crown victories. At age six, he won the Brooklyn, the Metropolitan, and the Woodward Handicaps before setting his sights on the Marlboro Cup at Belmont Park.

A Rolling Stone on Bad Ankles

By October 1976, Forego had logged forty-seven starts with twenty-eight victories and a reputation for carrying the heaviest of weights and still finding the finish line. He had carried 130 pounds or more sixteen times, winning at 135 pounds but finishing third twice at 136 pounds. He won the Woodward Handicap by one and a quarter lengths under 135 pounds and jockey Bill Shoemaker. What would racing secretary assign for the Marlboro Cup Handicap? Trainer Frank Whitely, who had taken over Forego’s training after Sherrill Ward’s retirement, figured 136 pounds was inevitable. Lo and behold, though, the list of weights for the Marlboro Cup had 137 next to Forego’s name.

On top of that, the track was sloppy after rain the night before and the morning of. A glance down Forego’s past performances would reveal a long list of fast tracks – and the lone sloppy track, ironically, was the 1974 Marlboro Cup, where he finished third by three lengths carrying only 126 pounds. This time, two years later, Forego was expected to carry eleven more pounds over a track that he disliked? Most owners or trainers would have shied at such, but not Martha Gerry or Frank Whitely. The difference? Bill Shoemaker’s report that the track might be wet on top but was fast underneath. Whitely decided that Forego would race.

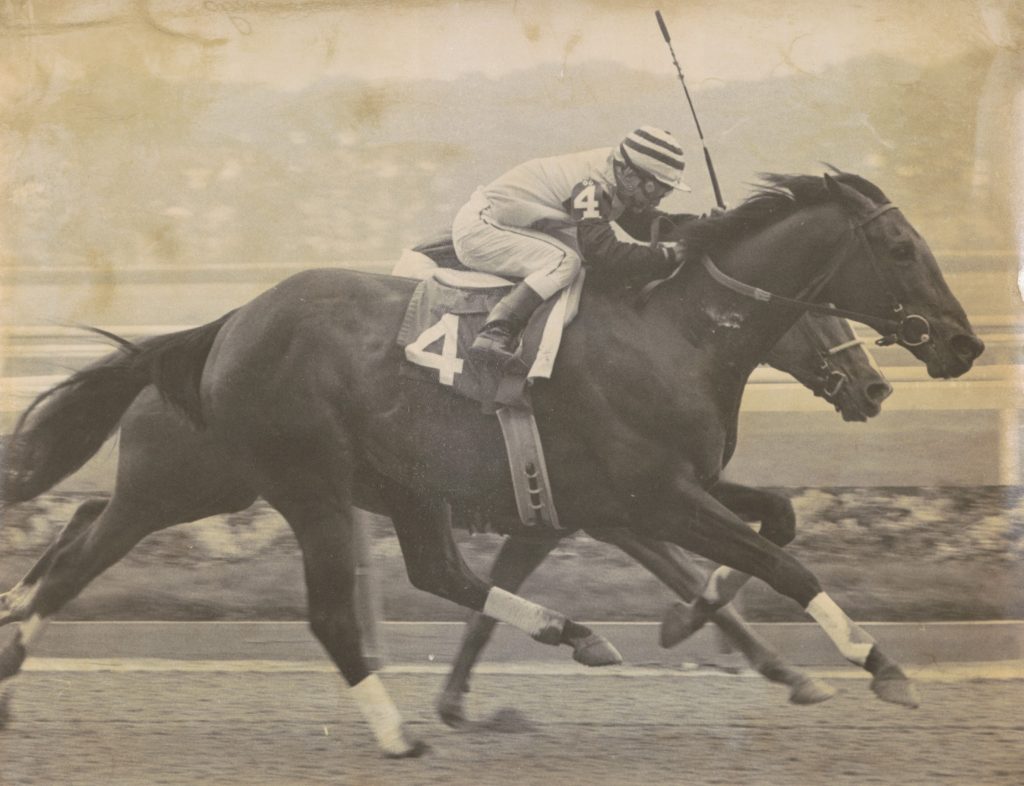

Forego joined ten others on the track for the Marlboro Cup, giving from 18 to 28 pounds to his competition. His biggest challenger was Honest Pleasure, the Travers Stakes and Florida Derby winner who benefited from being a three-year-old facing older horses: he carried only 119 pounds. Forego broke from post ten, with Honest Pleasure to his inside in post four. At the start of the ten furlongs, Forego was in the lead a few strides away from the gate, but Shoemaker allowed him to settle in behind horses as Craig Perret sent Honest Pleasure to the lead. On the backstretch, Honest Pleasure was in front by two lengths, with Forego still running on the outside way back in eighth.

At six furlongs, Honest Pleasure still held that lead, the leisurely pace of the first part of the race now quickening as the field rounded Belmont’s sweeping far turn. At a mile, Forego had improved his position from eighth to sixth, but he was still eight lengths behind, lugging almost twenty pounds more than Honest Pleasure. In the stretch, the three-year-old seemed poised to run away from the field, a familiar sight to those of us who have seen horses control the pace and then kick away in the stretch. But we also know those moments when the slow roll of the closers, those who seem hopelessly out of it, build enough momentum that suddenly they appear from out of the clouds to snatch the lead. That is exactly what Forego did.

Shoemaker was sure they were not going to make it, certain that they would not even be in the money. Perret had a lot of horse under him still, the confidence of youth striding underneath him, a plethora of power and speed on the precipice of victory. Nevertheless, Shoemaker waved his stick at Forego, never touching him, only reminding the determined gelding that it was time to go. On the outside, in the middle of the track, Forego seemed to move at a speed that would never be enough to catch the Travers winner on the front end. To the eye, did it seem like he moved in slow motion while the rest of the field aimed furiously for the finish line? With seventy yards to go, the wire looming, Forego was only a length and a half off of Honest Pleasure.

In the bare seconds it took to cover those final yards, the momentum of his stride, the grind of his heart, brought Forego to Honest Pleasure. At the wire, they were so close, so close, that not even Martha Gerry or Frank Whitely were sure of the outcome. Which number would come out on top?

When the number 10 flashed on the tote board, the crowd of 31,716 roared its approval. Forego became the first horse to win a mile and a quarter race carrying 137 pounds since 1935. He did it in 2:00, just a fifth of a second off the track record of 1:59 4/5 he set the year before, carrying five fewer pounds.

Afterwards, Bill Shoemaker said, “It was one of the greatest horse races I’ve ever been in or seen.”

A Titan Says Goodbye

Forego’s win in the Marlboro Cup was his final race of 1976, those pesky ankles necessitating a break until the following spring. Forego raced nine more times in his final two seasons, 1977 and 1978, before issues with bone chips and arthritis meant that it was time for the gelding to call it a career. At age eight, Forego retired with thirty-four wins in fifty-seven starts, his nine second-place and seven third-place finishes meaning that he finished out of the money only seven times in his six seasons of racing. His consistency and courage garnered his eight Eclipse Awards, including Horse of the Year in 1974, 1975, and 1976.

With his racing days behind him, Forego retired first to Home Place Farm and then the Kentucky Horse Park, living out his days in the same Bluegrass region where he was born. His exit from the racetrack marked the end of an era: handicap racing backed away from assigning such heavy imposts as horse racing evolved toward races like the Breeder’s Cup and others determining the year’s champions. As the last of the great weight carriers, Forego left a generation of fans in his wake, telling the stories of how this titan on questionable ankles rolled over his competition time and again. This great horse has been gone for nearly a quarter of a century now, but, in his wake, endures the memories of Forego’s grit and determination regardless of the obstacles laid before him, the embodiment of the best that a Thoroughbred can be.

Photo Credit: Keeneland Library