Photo Credit: Keeneland Library

When John E. Madden went to Louisville in May 1914, he was there to supervise the training of his filly Watermelon in preparation for starts in the Kentucky Oaks and Derby. The striking chestnut filly was Madden’s recent acquisition, her form promising but trainer William Walker knew how to win a Kentucky Derby and he would have liked for the filly to have had another start before she tried the boys. At this point, no filly had yet to win the Derby and Regret herself was only two and yet to make her debut. The odds were stacked against Watermelon, but Madden was an optimist and sold horses to a myriad of famous names in the sport – Whitney, Daly, Applegate – sometimes with only that very optimism on his side.

Imagine how that optimism might have wavered when Watermelon came in dead last, twenty-five lengths behind the winner, a bay gelding named Old Rosebud. And yet Madden must have finished the day with a smile on his face because his Hamburg Place had been the place where the winner first saw the light of the world and stretched his legs next to his dam Ivory Bells, the first of Madden’s eventual five Kentucky Derby winners.

A Little Guy

The gelding had not been a source of optimism for Madden initially: when New Louisville Jockey Club secretary Hamilton Applegate came looking for bloodstock, he purchased several fillies, ostensibly because fillies could become broodmares when they were no longer racing. Madden threw in the gangly colt that would become Old Rosebud for a reported $500. He was by Uncle, one of the few horses who almost defeated the immortal Colin. Still early in his stud career, Uncle was the one son of Star Shoot that might be counted as a good sire, as Sir Barton and Grey Lag later would prove to be average at best. In addition to Uncle’s speedy influence, Old Rosebud’s pedigree counted both Himyar, the sire of the immortal Domino, and Ida Pickwick, who had won Latonia Oaks and other stakes races. The pedigree alone might have prompted other breeders to keep Old Rosebud for themselves, but Madden was not inclined that to that kind of sentimentality. He was the one who had sold champions Hamburg and Sir Martin even after both had brought him success.

Applegate named the scrawny bay colt Old Rosebud, after one of the bourbons his family’s distillery produced. Despite his pedigree, Old Rosebud was gelded, likely to encourage his growth since he was undersized. Applegate then sold a stake in the gelding to trainer Frank Weir, who not only trained all of Applegate’s horses but also was his partner in racing. In February 1913, at Juarez, Mexico, one of the few racetracks that had winter two-year-old racing, Old Rosebud made his debut, winning his first start in the three-and-a-half furlong Yucatan Stakes by six lengths. He went on to win eleven more times that year, with Weir taking him from Juarez to Kentucky to New York. Old Rosebud won at Latonia and Churchill Downs, Douglas Park and Saratoga, setting a couple of track records and winning races like the Flash and the United States Hotel Stakes. He beat horses like Stromboli, stakes and handicap winner for August Belmont; Roamer, another gelding who would go on to legendary status as a champion himself; and Black Toney, who would later sire two Kentucky Derby winners. Old Rosebud finished 1913 as the champion two-year-old and the early favorite for the 1914 Kentucky Derby.

A Big Splash

At three, Old Rosebud showed clear signs of maturing, filling out his wiry frame even more. His great record at two augured for even better in 1914, with possible starts in races like the Kentucky Derby, the Wither Stakes, the Kentucky Handicap, and more. In addition, Applegate and Weir fielded high-dollar offers for the gelding from other owners like Jefferson Livingston, a condiment magnate who was looking for a Derby candidate to run in his colors. Livingston’s bid was $35,000 in early April but Old Rosebud was not to be had for under $40,000. Such ownership changes were not uncommon in the countdown to the Kentucky Derby; Exterminator would be purchased under similar circumstances, though for a different purpose, in 1918. Livingston was unwilling to match Applegate’s price for a gelding, a horse that Livingston would not reap long term gains from, so Old Rosebud went to the post for the 1914 Kentucky Derby in the Applegate colors.

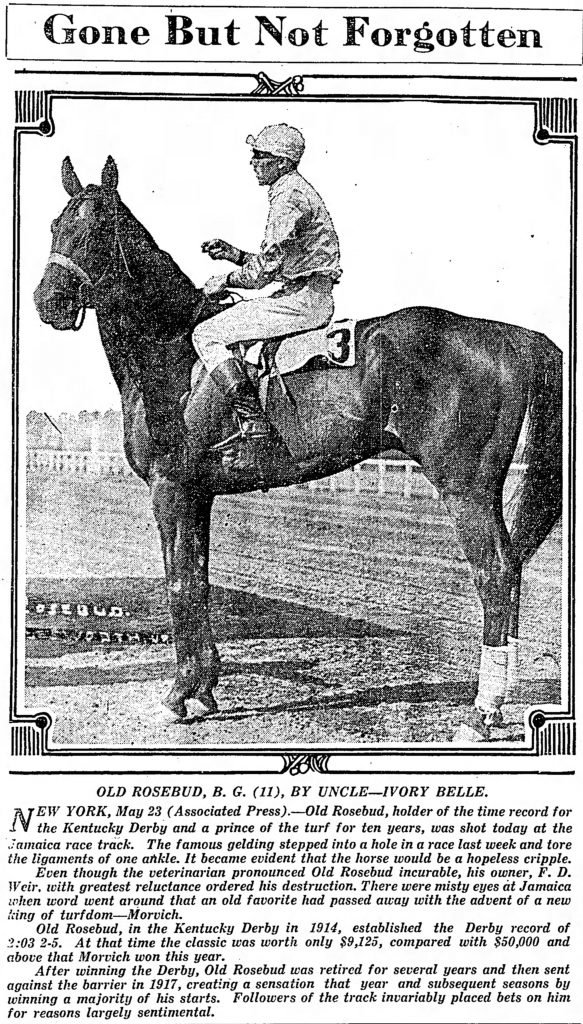

The year before, the Kentucky Derby had seen its biggest priced winner ever, with long shot Donerail paying $184.90 for a two-dollar bet. In 1914, the race continued its sensational rise with Old Rosebud bringing home the roses by eight lengths in record time, 2:03 2/5, over a track that wasn’t exactly fast. So sensational was the gelding’s time that it would take more than a decade before Twenty Grand lowered it to 2:01 4/5 in 1931. His winning margin of eight lengths has been equaled but not surpassed in the century plus since Old Rosebud won the Kentucky Derby. The gelding would be Hamilton Applegate’s only Kentucky Derby starter and Weir’s only victory in the Run for the Roses.

Weir then sent Applegate’s horses to Belmont Park, targeting the Withers Stakes for Old Rosebud’s next start. Prior to 1921, Belmont ran its races clockwise, inspired by the practices of our English brethren. Most racetracks ran counterclockwise so running at Belmont Park was an adjustment and Old Rosebud had difficulty making it. In the Withers, the gelding started out on the lead, but, as they rounded the final turn into the stretch, he went wide, taking Gainer with him. Lacking his usual speed, Old Rosebud couldn’t pass Gainer, slowing with each stride. Jockey Johnny McCabe practically pulled the gelding up as they crossed the wire, finishing fourth. His performance was a puzzle: after a champion two-year-old season and a record-breaking Kentucky Derby, what else could possibly have slowed Old Rosebud down?

In 1913, the gelding made his last start at Saratoga in mid-August and did not face the barrier again until the following April. Unbeknownst to most, Weir had rested his horse because he had shown soreness in his left foreleg. According to Weir in the Daily Racing Form in 1922, that injury had prompted conversations with Applegate about selling Old Rosebud, but a misprinted number of $30,000 had discouraged buyers. In the Withers, confused by running clockwise, Old Rosebud had fought McCabe and resisted changing leads, re-injuring that foreleg in the process. Weir declared the gelding done for 1914 and then used a firing iron to treat the area in an effort to induce inflammation and speed healing.

A century ago, geldings had few options for their post-racing careers. Unable to stand stud, most either raced until they were unable to be effective on a racetrack or were relegated to other purposes. The concept of aftercare would not become a reality until decades later. Weir and Applegate had every intention of bringing Old Rosebud back to the races. A year after his injury in the Withers, Weir put him back into training, but the gelding struck himself during a workout. An anticipated return in the fall of 1915 was delayed indefinitely, Weir sending the gelding to his friend Wade McLemore, who turned Old Rosebud out on his ranch in eastern Texas.

A Long Recovery

In late 1916, Weir visited his “Old Buddy” at McLemore’s ranch and found a healthy Old Rosebud running with the ranch’s younger horses, outpacing as they ran around the paddocks. Starting at Juarez the following February, Old Rosebud seemed back to his old form, winning the Clark, Queens County, Delaware, and Carter Handicaps, often carrying weights upwards of 133 pounds. He won 15 of 21 races that year, his comeback story making him a popular figure for the racing public. However, his aggressive season of racing likely re-aggravated that foreleg so Weir treated him with the firing iron again, opting to keep Old Rosebud off the track for the entirety of 1918. During the gelding’s convalescence, Weir also bought out Applegate’s share of their Kentucky Derby winner, leaving him with sole ownership of the gelding for the rest of his life.

At age 8 in 1919, Old Rosebud returned to the track once again. He would not run as well as he did in 1917, but he managed to win nine of his 30 starts that year, finishing in the money in another twelve. Like another famous gelding of the same era, “Old Buddy” continued racing well into his eleventh year, but in fewer and fewer races, mostly in allowance or claimer conditions. He made his last start on May 17, 1922, finishing seventh in a six-furlong allowance race at Jamaica Race Track. Five days later, Old Rosebud returned to the Jamaica oval for a workout. He stepped in a hole as he worked, injuring that left foreleg again. This time, though, neither a firing iron nor rest would fix this. He had torn ligaments in that leg and soon reality must have laid heavy on the horseman that called him companion. With decades of experience behind him, Frank Weir knew what had to be done. The next day, after exhausting all of the possibilities of recovery, after hugs and caresses from those who loved him best, a veterinarian ended Old Rosebud’s suffering. With that, a storied career, marked by a blanket of roses and two remarkable comebacks, was over.

A Century of Memory

Barely a year after he said goodbye to “Old Buddy,” Frank Weir died of a heart attack at the age of 65. Hamilton Applegate continued his career as part of the New Louisville Jockey Club, serving as treasurer and auditor at Churchill Downs until the 1930s. Old Rosebud’s longtime jockey Johnny McCabe rode many more horses in his career, but Old Rosebud was his best and perhaps his best loved. He represented the 1914 Kentucky Derby winner when the gelding was inducted into the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in 1968. McCabe spoke fondly of “Old Buddy.” calling him “as good as any of them – Man o’ War, Count Fleet, Citation, Secretariat.” A part of the eternal pantheon of champions, Old Rosebud, a horse of tremendous heart, blooms still with eternal greatness.