Hoist The Flag

An eerie quiet settled over the barn, like time itself held its breath for what was next. Every exhalation was agony, the scene all too familiar to anyone who works with horses: for all of the power and grace they possess comes a proportional amount of fragility and misfortune. At the stall’s door stood a man who had seen tragedy and triumph in battle and on the track. Quiet, he choked back tears as he listened to the loving murmurs of a groom comforting his charge, his right hind leg held delicately off the straw. With a step, the world had broken; with the next one and then the one after that, the day almost ended with an absence, an inevitability in most cases. Even with Derby dreams shattered, though, today’s tragedy was not absolute.

Hope settled over the scene. Everything that could be done would be, no expense spared, no problem left unsolved. All of it lay within one horse’s will to win becoming his fight to survive – and maybe even thrive.

The Threads We Weave

John Schiff’s Wavy Navy had been an average racehorse. In her thirty-five starts, she had won only twice, though she had finished in the money thirteen other times. Where she fell short on the racetrack, she excelled in pedigree: her sire was the 1937 Triple Crown winner War Admiral and her dam was a winner both on the flat in France and over the jumps at Belmont Park. In 1967, Schiff sent Wavy Navy and another mare, Pradella, to Claiborne Farm to visit Tom Rolfe, classic winner and three-year-old champion of 1965.

Tom Rolfe had had a celebrated career which saw him just miss being named Horse of the Year by one vote. After finishing third in the Kentucky Derby, he won the Preakness Stakes before finishing second in the Belmont. He also won the ten-furlong American Derby in track record time at age three and then the Salvator Mile and Aqueduct Handicap at age four. When Schiff sent Wavy Navy to Tom Rolfe, he was taking a chance on an unproven sire, but one with a proven pedigree. Tom Rolfe’s sire was Ribot, the last champion even bred by famed Italian breeder Federico Tesio and twice winner of the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe in France. His dam Pocahontas had already produced Chieftain, winner of the Arlington Handicap, but Tom Rolfe would be her best son.

From the pairing of Wavy Navy and Tom Rolfe came a bay colt with a diamond-shaped stamp of white on his fine forehead, Hoist the Flag. His late March debut was about the same time as Pradella’s colt’s, but soon both presented a bit of a problem for their breeder. Schiff was approaching a business-related deadline that meant he needed to sell some horses. With that date looming, Schiff asked friend John Gaines, founder of Gainesway Farm and creator of the Breeder’s Cup, to look over his weanlings and pick those he would like to buy privately. Gaines selected two, one of them Wavy Navy’s colt by Tom Rolfe. Claiborne Farm’s Arthur “Bull” Hancock and others told Schiff he was “a damn fool” for selling either of those Tom Rolfe colts. Schiff, though, needed to show a profit to stave off any tax penalties so he had to sell. “I didn’t listen to any of them,” Schiff said later. “I guess I was too busy with my business. It was quite stupid of me.”

Gaines took a consignment of horses, including Hoist the Flag, to Saratoga for the yearling sale. The sale was scheduled to start Friday, August 8th. Two days earlier, Stephen Clark, Jr. and his wife Jane accompanied trainer Sidney Watters, Jr. to an inspection of the yearlings up for sale. They sought out the Gaines horses, which include Wavy Navy’s yearling, and gave the studdish colt a look. He had bruised his eye on the trip up from Kentucky and he was from an unproven sire, but the Clarks were smitten. They decided they wanted him and authorized Watters to buy him. Also bidding was trainer George Poole, there on behalf of C.V. Whitney; Poole’s budget was $35,000. As the bidding got closer to that threshold, Poole tried to get a hold of Whitney to see if he might bid higher, but was unsuccessful. Poole threw in an additional $1,000 out of his own pocket, sending the colt to $36,000, but couldn’t go any higher. On the heels of that bid came Watters offering $37,000 on behalf of the Clarks. Gaveled home at that price, Wavy Navy’s colt out of a new sire would show why Schiff lamented letting go of that particular horse. For the Clarks, this bargain would show he was worth so much more.

The Clarks were part of a family with a long history of equine pursuits. Stephen, Jr. was the great-grandson of Edward Cabot Clark, Isaac Singer’s partner in the Singer Sewing Machine Company. His uncle Robert Singer Clark had been both an art collector and a long-time owner of a small racing stable, counting the Kentucky-bred Never Say Die, winner of the 1954 Epsom Derby, as his most famous racer. Another uncle, F. Ambrose Clark, owned Kellsboro Jack, the third American horse to win England’s Grand National. Stephen, Jr. and his wife Jane both were raised with horses and owned steeplechasers in addition to a few flat racers. Through their time as part of the steeplechase scene in Virginia, they met trainer Sidney Watters, Jr.

Watters grew up around fox hunters and racehorses on his family’s farm near Monkton, Maryland. His father was also a trainer and started young Sidney out as a steeplechase rider at Saratoga at age 16, winning almost 50 races before World War II intervened. Sidney, Jr. served as a gunner in the Pacific theater for four years before returning home to train rather than ride. Watters trained for both the jumps and the flat, working for owners like Richard Mellon and the Clarks. He had trained Amber Diver and Shadow Brook, both steeplechase champions, for the Clarks. Now, with this Wavy Navy colt, Watters was looking to add another champion to his résumé.

The Pattern We See

At two, Hoist the Flag was slow coming to the races, sore shins keeping him on the sidelines until Watters felt he was ready to race. Finally, as autumn approached, the trainer decided on a six-furlong maiden special weight race at Belmont Park. On September 11, 1970, Hoist the Flag made his debut.

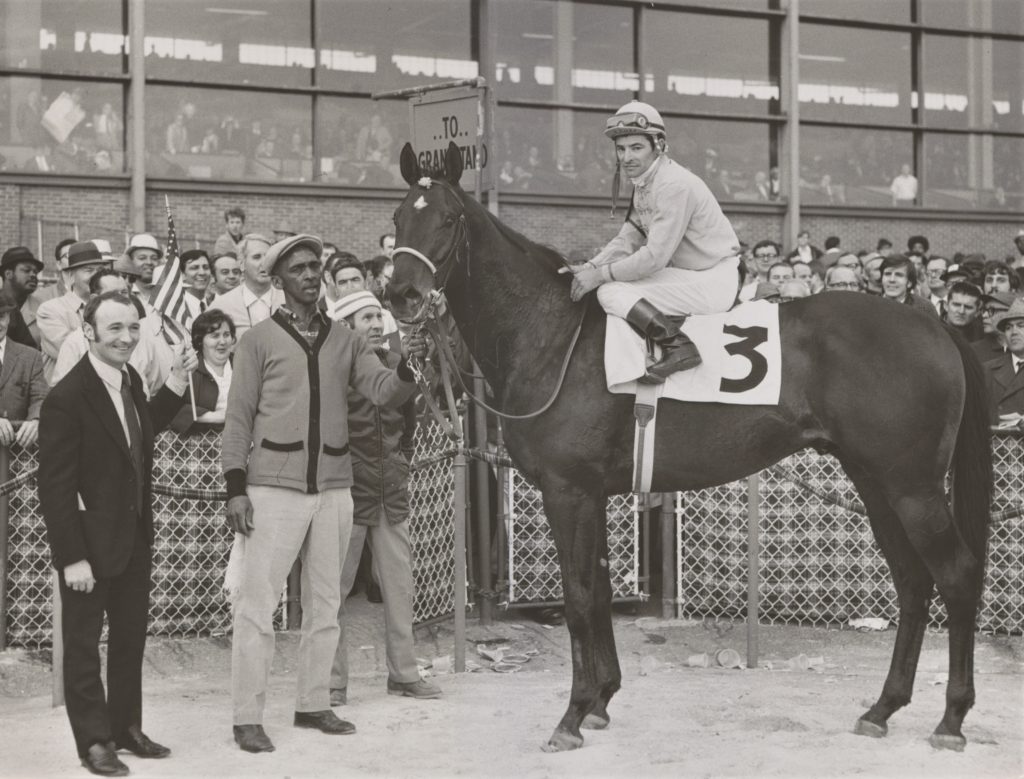

Ridden by French jockey Jean Cruguet, Hoist the Flag broke last in the field of eleven, found a middle position by the first quarter, and then grabbed the lead by a head entering the stretch. At the wire, he was two and a half lengths ahead of the field, breaking his maiden on his first try. Twelve days later, Cruguet and Hoist the Flag were back at Belmont for the colt’s second start, a 6 ½ furlong allowance race. This time, Wavy Navy’s colt had the lead by the first quarter and cruised to win by five lengths. The New York Daily News’s Jim McCulley called him “perhaps the top two-year-old colt in the land” in only his second start. For his next start, Watters opted to start Hoist the Flag in stakes company for the first time. Again at Belmont Park, the colt joined eleven others for the seven-furlong Cowdin Stakes.

Formerly known as the Junior Championship Stakes, the Cowdin counted a number of classic winners and at least one Triple Crown winner among its historic victors, including Tom Rolfe, Hoist the Flag’s sire. For the 1970 edition, Hoist the Flag faced eleven others, including the colt Limit to Reason, owned by Brookmeade Stable. Again, he broke slowly, hanging out toward the back of the pack for the first half-mile. Four furlongs in, Cruguet had Hoist the Flag in fifth with three furlongs to go. At the top of the stretch, they were in second, bearing down on front runner Limit to Reason with a ferocious closing kick. At the wire, Hoist the Flag had won the Cowdin by 1¾ lengths in 1:22 2/5, one second off the track record. With that, Hoist the Flag was among the favorites for champion two-year-old colt of 1970. A victory in his next race, the Champagne Stakes, would guarantee the championship for the Clark’s colt.

As old as the Belmont Stakes, the Champagne is an annual test for two-year-olds and, at a mile, one of the longest. The race’s list of past winners includes some of history’s best horses, including Colin, Count Fleet, Buckpasser, and more. The field was the largest Hoist the Flag had faced to that point, with sixteen horses total. Limit to Reason and four other stakes winners were all set to face the starter, but none of the others were really a threat to the Cowdin winner. Instead, Hoist the Flag would become his own worst enemy.

Breaking from the 10th post, Cruguet sent his colt to the front of the pack, sitting in third to avoid the traffic jam of a field of 16 two-year-olds trying to get in the right position for the eight furlongs. By the half-mile, Cruguet had Hoist the Flag on the lead, sending him to the rail, where the colt preferred to run. In doing so, he came over in the path of Close Decision. Though Hoist the Flag won as he pleased, his path to the winner’s circle was stymied by the flashing inquiry sign. The stewards disallowed one claim of interference against Cruguet and his horse only to levy one of their own, disqualifying Hoist the Flag for interfering with Close Decision. Though he had come home first, the record shows that Hoist the Flag was placed last, the one and only time he would ever lose a race.

After four starts in a month, those sore shins bothered Hoist the Flag again, Watters opting to send his colt to winter quarters in South Carolina rather than race again in 1970. In December, this son of Tom Rolfe was voted the two-year-old colt of the year. By early spring, Hoist the Flag was the early favorite for the 1971 Kentucky Derby, with Watters laying out a specific route for his hopeful, a progression of races starting at six furlongs and progressing to nine furlongs in anticipation of the Derby’s mile and a quarter. While other Derby hopefuls were starting their year in Florida and California, Watters kept Hoist the Flag in South Carolina until March. Their target for the champion’s first start of the year? A six-furlong allowance race at Bowie.

The Banner We Fly

When the Jockey Club’s Experimental Handicap weights came out in January 1971, Tom Rolfe was well represented in the rankings of the year’s top three-year-olds. The first three were all sons of his: Ruffinal, whose dam Lea Lane was by Nasrullah, one of Europe’s top sires; Run the Gantlet, who damsire was First Landing, sire of the next year’s star Riva Ridge; and, of course, at the top of the list was Hoist the Flag. Four starts, four wins (almost), and only four months until the Kentucky Derby. But Sid Watters wasn’t in a hurry to get Hoist the Flag back to the track.

His spring training started down south in Camden, South Carolina, where he prepared for his first start at Bowie Race Track on March 12th. Those sore shins had kept him away for five months and yet his trainer wasn’t the least bit concerned about the seven weeks between here and Louisville. As they wound their way north to New York for the serious preparations, they stopped in Maryland for that overnight allowance, a tune-up for what was next.

The six-furlong allowance had only four other horses entered, none quite the same caliber as Hoist the Flag. His performance showed how he was far and away the best horse that day, taking the lead before the first quarter and then drawing away to win the race by fifteen lengths. Cruguet galloped his horse out for another furlong and then eased him as they approached a mile. Sid Watters was pleased with the performance, declaring the seven-furlong Bayshore Stakes at Aqueduct as their next stop on the path toward roses. His years on the steeplechase circuit may not have been the same as treading this path to the Kentucky Derby, but, if Watters had any nerves about preparing his colt for that goal, he did not show them.

In the Bayshore, Hoist the Flag faced a field of eight other three-year-olds, with a couple of familiar faces in the lineup: Limit to Reason, the beneficiary of the Flag’s disqualification in the Champagne and Droll Role, the other Tom Rolfe colt that John Schiff bred. As Hoist the Flag got closer to the Kentucky Derby, his level of competition over these successive starts would get higher and higher. Not every horse in this field was aimed for the classics, but Limit to Reason and Droll Role presented his toughest competition yet.

But they weren’t. From the six post, Hoist the Flag broke faster than usual, jumping out to second just behind Rehitch. On the final turn, he vaulted to the lead, entering the stretch with a four-length lead. At the wire, Hoist the Flag finished seven lengths in front in the fastest seven furlongs run at Aqueduct that spring and setting a stakes record for the Bayshore. It was the kind of performance that augured well for what was next. As Sid Watters reported, their next target would be the Gotham Stakes, a one-mile prep race two weeks later. If all went well, another race six weeks hence, this one in Kentucky, was their ultimate goal.

“If he didn’t lose today,” Jean Cruguet said after the Bayshore, “I don’t think he’ll ever get beaten unless he falls down.”

Hoist the Flag may have had boundless potential, but the physique of a horse has its limits, as fate has reminded us all time and again.

The Courage He Needed

Jean Cruguet came to Belmont for this workout at the request of Sid Watters. Usually, Colum O’Brien, an Irish steeplechase jockey, would work Hoist the Flag, but this workout was different. He was preparing for the Gotham Stakes four days later. Watters asked Cruguet to breeze the colt five furlongs, which he did in 1:01 4/5, a shade faster than the trainer had asked. Then the French jockey felt a jolt: Hoist the Flag’s right hind leg had given way, but the momentum of his stride carried him another half-furlong. The first jolt meant a fracture; the next few strides were a pulverizing.

Hoist the Flag had broken his leg, breaking his cannon bone and shattering his long pastern bone.

Sid Watters and the colt’s devoted groom Rob Cook sprinted for their beloved charge, the equine ambulance on their heels. The colt staggered into the ambulance on his three good legs while the three men looked on helplessly. They knew what the sight of that dangling leg meant: grim news, hushed tones, an empty stall. As they followed the ambulance back to Watters’s barn, Barn 38, they all knew the situation was grave. Watters called the Clarks at home in Virginia. Veterinarian Mark Gerard felt the colt’s leg and knew that, at the very least, Hoist the Flag would never race again, but this kind of injury usually meant the end of a horse’s life. The veterinary representing the Clarks’ insurance company had already authorized that. Gerard advised that they wait for x-rays.

The x-rays showed the worst: the pastern bone had been shattered into pieces, the cannon bone with a fracture that was nearly half its length, and the base of that bone split at the ankle. When they broke the news to the Clarks, Jane Clark said, “Save him at all costs – as long as he doesn’t have to suffer.” The owners flew to New York to be with Hoist the Flag as he underwent surgery to set the fractures and hopefully save his life. Fortunately for the Flag, a new surgical technique and the colt’s own impeccable health would be his saving graces.

At Dr. William Reed’s equine hospital, a team of three surgeons worked on repairing the colt’s leg in a six-hour operation. Dr. Jacques Jenny, a professor of orthopedic surgery at the University of Pennsylvania’s Bolton Center, led the team with Dr. Reed and Dr. Donald Delehanty of Cornell University’s Veterinary School working on the complicated rebuilding of Hoist the Flag’s leg. They used stainless steel clamps and screws, adapted from human orthopedics, to secure the cannon bone. They then used bone marrow grafted from the colt’s hip to fill in the gaps in the shattered pastern while securing the bone with a steel plate and screws and even steel wire to help in rebuilding the bone as the colt healed. Nearly forty years later, similar techniques would be employed to repair 2006 Kentucky Derby winner Barbaro’s fractured leg; in Barbaro’s case, sadly, laminitis and other complications would become too much for him and he eventually would lose his battle.

Hoist the Flag, though, had fortune on his side. Even in the midst of the tragic end to his racing career, the colt’s good health and the nature of his fractures saw him through his recovery. An infection in the graft site caused some complications, but a second surgery and that bodily fortitude saw him through to the other side. He continued to act as a model patient, enduring cast changes and the tedium of rehabilitation. Fans sent the Clarks notes of concern and wishes for their colt’s speedy recovery, with Jane Clark responding to each one with a note and photo of her beloved horse. Sid Watters had shared tears as his horse had gone from Derby-bound phenom to a patient on the precipice. He had endured the travails of the Flag’s recovery alongside the Clarks and sighed with relief as the colt continued to recover.

In November 1971, long after that year’s Triple Crown was run, Hoist the Flag boarded an airplane for Lexington, Kentucky. A van met them when his plane landed, the colt limping into the trailer bound for what’s next. At the other end of this journey were the familiar rolling paddocks of Claiborne Farm and a stall in their famed stallion barn. His racing career might be over, but Hoist the Flag had come full circle, back to where he was born, with a chance to impact the sport in another way: through his foals.

As a sire, Hoist the Flag peaked at number two on the sire list in 1978 and was champion broodmare sire in 1987. He sired Alleged, who won the Prix d’Arc le Triomphe twice, and Sensational, champion two-year-old filly of 1976. His daughter Grecian Banner proved to be an ineffectual racehorse, but a Reine-de-Course as a mare, with five foals who were winners on the track, including the undefeated Hall of Fame mare Personal Ensign. The latter was the dam of Our Emblem, sire of War Emblem, the 2002 Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes winner. Another daughter, Naval Orange, produced Cryptoclearance, Grade I stakes winner who sired 1998 Belmont Stakes winner Victory Gallop. Hoist the Flag’s time at stud gave him the chance to impact the sport over and over again, his influence still felt today, nearly fifty years after that fateful day.

The Legacy He Left

In March 1980, Hoist the Flag suffered another fracture, this time in his left foreleg. Like his original injury, surgeons used plates and screws to stabilize the bone, but this time he was not able to overcome the injury. On May 17th, the horse that had fought through one traumatic injury succumbed to this one. At age twelve, he was still a relatively young stallion, but he was able to sire a number of winners even in his short time at Claiborne. As a sire, he gave us champions; as a racehorse, he left those who saw him with chills. To this day, his jockey Jean Cruguet calls Hoist the Flag the best horse ever rode, even after winning the Triple Crown with Seattle Slew in 1977.

Nearly fifty years after his career ended suddenly, we celebrate the life of Hoist the Flag as a demonstration of how the will to win can also become a weapon in the fight for life. He may not have been able to show all that he was capable of on the track, but his sons and daughters spoke for him, winning famed races on multiple surfaces and multiple continents in the years since he left us. He is a reminder of the love that brings people back to horse racing again and again, to celebrate the triumphs and mourn the tragedies together, all of us focused on these equine stars at the center of the story.

Photo Credit: Keeneland Library Thoroughbred Times Collection

These photos are used with the express permission of the Keeneland Library and may not be used or reproduced without express permission.