War Admiral and jockey Charles Kurtsinger after the 1937 Preakness (Keeneland Library Morgan Collection)

By Andrew Hanna

Triple Crown winner War Admiral has a history of being misunderstood. Throughout his career, he was viewed as brilliant but tempestuous. Today, he’s best remembered for losing to Seabiscuit in the 1938 Pimlico Special– a gripping match race that was voted the second-greatest moment in the sport’s history.

The truth about War Admiral was more complex. Outside of the 1938 Pimlico Special, he only lost one other race– the 1938 Massachusetts Handicap– from the start of his three-year-old season to his retirement. Though he could be very high-strung in the starting gate and around crowds, he also had a calmer side. “Time after time,” says author Dorothy Ours, “visitors described how relaxed War Admiral was in his racetrack stall. You might even sneak up on him. Before dawn on Belmont Stakes morning, a photographer found the Triple Crown hopeful sprawled on the straw, sound asleep.” Finally, War Admiral was a tenacious runner who showed “joy and courage in competition.”

“When competing,” Ours elaborates, “he was honest. Running lines from his 26 races show War Admiral’s heart. A couple of them say ‘hard drive.’ A couple say ‘weakened.’ None say quit.”

War Admiral came into the world on May 2nd, 1934 at Samuel D. Riddle’s Faraway Farm. While he was a late foal, he boasted a royal pedigree. His dam, Brushup– who stood 14.3 hands high and came from a line of small horses– was a daughter of Belmont Stakes winner Sweep. The “short-legged and long-bodied” Sweep was by Ben Brush, a two-time champion and Hall of Famer. Through his dam, Pink Domino, Sweep could also trace his lineage to Domino: the 1893 Horse of the Year whose American earnings record stood for fourteen years.

As if that weren’t enough, War Admiral’s sire was the legendary Man o’ War. Running under Samuel Riddle’s colors, the stallion raced twenty-one times and only lost once. During his life, Man o’ War was so highly regarded that he was named an honorary colonel by the First Cavalry Division. He would later be rated the best American racehorse of the 20th century.

At first, the only trait War Admiral seemed to have inherited was his mother’s size. “When he came up from Kentucky as a yearling,” Sam Riddle elaborated in his diary, “he was about as big as a goat. Nobody paid any attention to him. While he worked very well at the farm, we had rather a heavy boy on him, and in consequence he never showed.” Per pedigree expert Avalyn Hunter, “Riddle was so unimpressed by War Admiral as a foal that he tried to sell the undersized colt to his nephew by marriage, Walter Jeffords. Although Jeffords liked the colt, he refused, fearing a family quarrel if War Admiral turned out well.”

Since Riddle couldn’t sell War Admiral, he sent him to trainer George Conway to try and make a racehorse of him. Born in Oceanport, New Jersey, Conway had gotten his start as an exercise boy in 1888 before joining Riddle’s stable in 1917. After being promoted to foreman, he assisted trainer Louis Fuestal with Man o’ War: “the great horse,” one journalist wrote, “was his special care.” Conway became Riddle’s head trainer in 1926– and promptly sent future Hall of Famer Crusader out to win the Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Suburban Handicap, and Horse of the Year honors. “Among horsemen,” a scribe noted in 1937, “Conway is known as a kindly old gentleman with a fine knowledge of horses. Seldom does one hear a swear word around his stable– not that the 64-year-old trainer doesn’t approve of it– but it just isn’t done. ‘Darn’ is a strong word for him to use.”

War Admiral and Conway clearly worked well together. Though the colt leveled off at only 15.2-1/2 hands– four inches shorter than Man o’ War– he quickly proved he was a force to be reckoned with. “When we got down to Havre de Grace in the spring of the year [probably 1936],” Riddle recalled, “Dr. R.D. Connely, the great veterinarian, was there. One morning we were trying him [in a workout], and for the first time War Admiral opened our eyes… [Connely] asked what I thought of him, and I said he was all right. But from that time on we were careful of this little horse. We were satisfied that we had something very nice, and fast, much better than an empty stall.”

Once he’d earned Riddle’s respect, War Admiral didn’t disappoint. On April 25th, 1936, the colt went postward in a maiden race at Havre de Grace. After being a “keen factor in the early running,” War Admiral “came courageously when straightened into the home stretch” and held on to win by a nose. A month later, he triumphed by two lengths as a 10-1 longshot.

Conway now knew his colt was ready for harder competition. On June 6th, he sent War Admiral after Belmont Park’s National Stallion Stakes– where he would face rising stars like Pompoon and Fencing. War Admiral “closed gamely” to finish third. After being shipped to Aqueduct, he was entered into the Great American Stakes. With jockey Charley Kurtsinger in the irons, War Admiral sped into the lead and hit the stretch in front. He was looking like the winner until he “swerved out” and was overtaken “in the last sixteenth” by the fast-closing Fairy Hill.

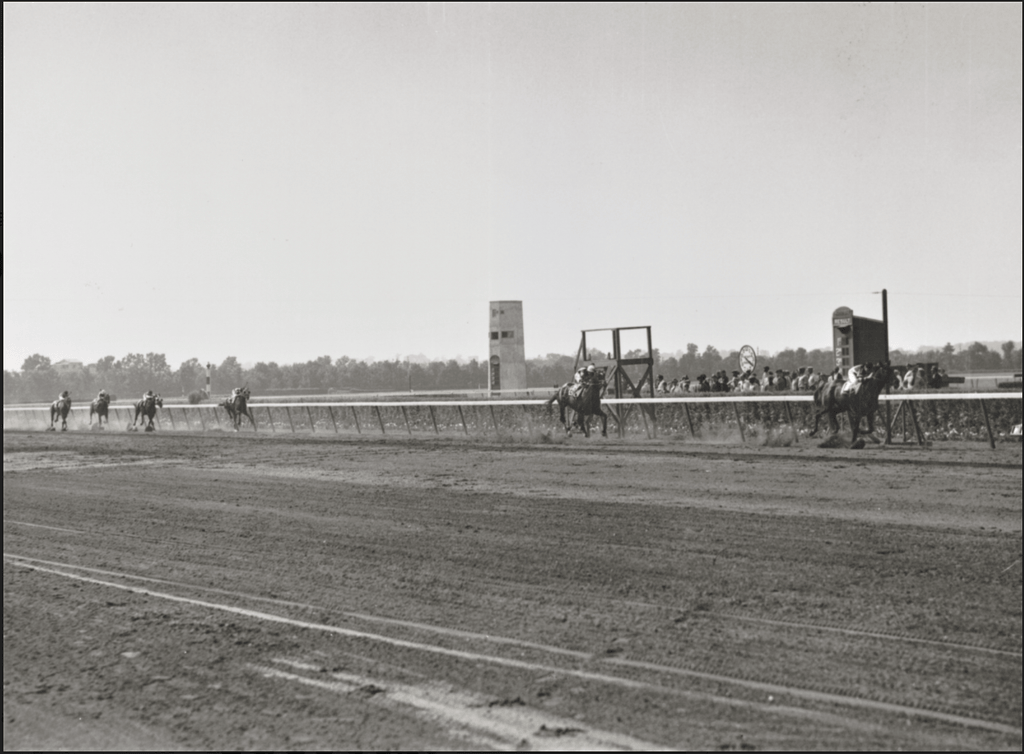

After that disappointing miss, Conway gave War Admiral a couple of months on the sidelines before sending him after the six-furlong Eastern Shore Handicap. The colt gave a performance to remember. In front of 17,000 spectators, War Admiral burst from the starting gate and drove into the lead. As his fourteen opponents struggled hopelessly after him, the colt pulled away and flashed under the wire, five lengths in front. His time of 1:11 set a new stakes record and narrowly missed the track mark. “Riddle, viewing the race from the club house, merely smiled after the victory,” a journalist noticed, “but it could be easily seen that through War Admiral’s performance today, the white-haired veteran was visualizing another Man o’ War.” The colt closed out his juvenile season with a hard-fought second in the Richard Johnson Handicap.

War Admiral returned with a vengeance the following year. After warming up with an allowance win, the colt appeared in the Chesapeake Stakes. “Eager to start,” a witness wrote, “War Admiral got away first after a delayed start and was never headed.” Without being extended, he won by six lengths. When asked about his colt’s showing, George Conway simply declared, “He ran like a champion.” He then confirmed that War Admiral would start in the upcoming Kentucky Derby. Though the colt was viewed as a top contender, his entry hadn’t been a foregone conclusion. Sam Riddle was infamous for skipping the Derby– mostly notably with Crusader, American Flag, and Man o’ War. According to the National Museum of Racing, the owner “believed that running 1-1/4 miles in early May was too demanding for 3-year-olds that were still not fully developed… it was never known why Riddle changed his mind and allowed War Admiral to run in the Kentucky Derby.”

On May 8th, the owner was rewarded for his change of heart. “It wasn’t a race at all,” said writer Warren Brown. “It was a parade, from flag-fall to finish.” After a sharp break, Charley Kurtsinger sent War Admiral to the front and kept him there. The colt drew away easily. In the homestretch, Pompoon– the 1936 Champion Two-Year-Old Colt– rallied and opened eight lengths on the rest of the field, but he couldn’t hook War Admiral. The Riddle colt coasted under the wire to win by two lengths. With their win, Kurtsinger became the third jockey to ride three Derby victors.

A week later, War Admiral and Pompoon met again in the Preakness Stakes. The largest crowd in Pimlico’s history showed up to watch them race. In a preview of things to come, War Admiral responded to the clamor by acting up. “As in the Derby,” reported Jesse Linthicum, “War Admiral would not stand still when the eight thoroughbreds walked into the starting gate… War Admiral walked right through the gate. He again was led into the No. 1 compartment, and he backed up. A dozen times he disobeyed and held up the start.” It took nearly four minutes for him to quiet down.

When the gates finally opened, War Admiral surged into the lead. Pompoon went with him. The two colts dueled down the backstretch and left their other opponents behind. In the homestretch, Pompoon slashed War Admiral’s lead to a head but stalled “in the final twenty yards.”

Kurtsinger was ecstatic. “Pompoon caught us on the stretch turn, but Wayne Wright had to take him inside, while I stuck to the better ground,” he explained. “I just clucked to War Admiral and he spurted ahead. I never used my whip. That little hoss just picks up his weight and moves forward.”

After War Admiral’s Preakness win, most fans were hoping for him to give an unforgettable performance in the Belmont Stakes. The colt didn’t disappoint. He “dragged a bewildered assistant starter through the starting gate several times before he was eventually contained”– holding the race up for eight minutes. At the break, War Admiral exploded forwards and “grabbed a quarter when his hind foot cut an inch-square chunk out of his right forefoot.”

Instead of easing up, the colt made a frenzied bid for the lead. He opened daylight on the others within the first 1/4-mile and never looked back. With blood running down his leg, War Admiral scorched past the finish in 2:28-3/5– breaking Man o’ War’s track mark, equalling the American speed record, and completing his sweep of the Triple Crown. “After that mishap at the start,” Kurtsinger declared, “… I never never had any doubt about the outcome. All I had to do was sit there and let the colt do the rest. He’s in a class by himself.”

Besides confirming War Admiral as the best horse of his generation, the Belmont gave him a reputation for being tempestuous and hard to handle. It was only partly true. “He’s just a little pet,” his groom, Roger Whittington, told the Associated Press. “Nothing bothers this horse except the excitement at the starting gate. We can do anything with him.” According to Dorothy Ours, the colt’s tantrums at the post also had an explanation. “War Admiral and Man o’ War both became notorious for being over-eager at the start,” she says. “But this wasn’t mindless misbehavior. Jockey Johnny Loftus “shook up” two-year-old Man o’ War to make him more alert at the barrier… [and] War Admiral had similar experiences at the gate with Charley Kurtsinger, developing a habit of popping through the doorless stall.”

Due to the injury he incurred in the Belmont Stakes, War Admiral didn’t race again until late October. He hadn’t lost an ounce of his form. After easily winning an allowance race, the colt– now nicknamed the “Mighty Atom” because of his ability and small size– was entered into the Washington Handicap. Facing older horses for the first time, he grabbed the early lead and held it for the entire race. It was his seventh straight win.

Four days later, War Admiral tried to extend his streak to eight in the Pimlico Special. Despite being assigned nineteen pounds more than his closest opponent, he was installed as the overwhelming favorite. The race didn’t go smoothly for War Admiral. After holding up the start for more than five minutes, the colt “broke well” but fell into third. With Masked General leading the way under a 100-pound impost, the field hit the backstretch and bent into the final turn. War Admiral was still lagging behind. With Kurtsinger working the whip, he inched into second before stalling. The Triple Crown winner was on the verge of defeat when Masked General went wide and bolted “for the outfield fence.” The Mighty Atom overhauled him to win by 1-1/2 lengths. “War Admiral sang his swan song for the year at Pimlico yesterday afternoon,” wrote journalist Don Reed, “… but there were enough sour notes in his song to leave echoes lasting all winter, if not for all time.”

At the end of 1937, War Admiral was named Horse of the Year– beating the great Seabiscuit. It was a somewhat controversial decision. Like War Admiral, Seabiscuit had enjoyed a spectacular year– winning ten stakes races, breaking four track records, and becoming the season’s leading money-earner. Unlike the Riddle colt, Seabiscuit had started his career as a claimer and raced fifty-seven times before he was four. He emerged from obscurity in 1937 to become the Champion Handicap Male. However, many fans felt Seabiscuit– not War Admiral– ought to have won Horse of the Year honors. It was the beginning of one of racing’s most intense rivalries.

Coming into 1938, Conway and Riddle were eager for War Admiral to defend his title. After the colt captured an allowance event, his handlers pointed him at Hialeah’s Widener Handicap. There, the Mighty Atom would compete for the richest purse of his career– and be forced to shoulder 130 pounds. He met the challenge easily. On March 5th– the same day Seabiscuit lost the Santa Anita Handicap by a nose– War Admiral romped through the Widener to win by 1-1/2 lengths. “War Admiral was king,” an observer insisted. “All others were merely at the track.”

With the demand for a Seabiscuit-War Admiral match race growing by the day, the Mighty Atom headed north. After missing three months of racing, he appeared in the Queens County Handicap. The colt extended his win streak to eleven under 132 pounds. Next, both he and Seabiscuit were entered into the Massachusetts Handicap. Just when it looked like the world would finally find out which of them was the better runner, Seabiscuit was forced to pull out because of swelling in his right forefoot. War Admiral stayed in.

From the outset, it was clear it wasn’t his day. The colt broke poorly and fell behind Menow– who’d been assigned 107 pounds. War Admiral couldn’t get within two lengths of him. He made a respectable try in the homestretch before kicking his foreleg near the three-eighths pole. As the crowd of 66,000 looked on, the colt sagged under the wire in fourth. His fans were aghast. “No great champion,” wrote Grantland Rice, “was ever beaten as badly as War Admiral was in this $50,000 test. The brilliant son of Man o’ War was run completely off all four feet. It would have been the same if he had had six feet, or had been a centipede.”

War Admiral rebounded quickly from his defeat. Since any match race against Seabiscuit had been delayed indefinitely, the Riddle colt was shipped to Saratoga for the Wilson Stakes. He won by eight lengths. Just three days later, the Mighty Atom strode to the post for the Saratoga Handicap. He shot into the lead after the break and hit the homestretch two lengths in front. War Admiral was looking like an easy winner when Esposa– the 1937 Champion Handicap Mare– unleashed a furious rally and slashed into his lead. The colt held on to win by a neck.

On August 20th, War Admiral and Esposa clashed again in the prestigious Whitney Stakes. Despite running under a different jockey for the first time since 1936– Charley Kurtsinger had been injured in the previous week’s Spinaway Stakes– the colt was superb. With Esposa challenging him throughout, War Admiral hurtled through the Whitney in stakes-record time and triumphed by a length. He went on to rack up effortless wins in the Saratoga Cup and the Jockey Club Gold Cup.

After War Admiral’s latest string of victories, the only horse standing between him and consecutive Horse of the Year honors was Seabiscuit. That fall, Alfred Vanderbilt– Pimlico Racetrack’s twenty-six-year-old president– set out to bring both stars to his track. It took all his business acumen to convince their owners to accept. “I told them [Sam Riddle and Seabiscuit’s owner, Charles Howard] that this was just a little track and we couldn’t put up a lot of money, but that it would be a good thing for racing, which they both liked,” Vanderbilt later explained. “It took a little doing.” Eventually, Riddle and Howard agreed that War Admiral and Seabiscuit would meet in the November 1st Pimlico Special– which would be turned into a $15,000, winner-take-all match race. Riddle also insisted that both horses would begin with “walk-up” rather than break from a starting gate. Because of his staggering starting speed, War Admiral was installed as the 1-4 favorite. Seabiscuit was sent off at 11-5 odds.

On race day, 40,000 fans flooded into Pimlico– which then could only hold 16,000. Consequently, Vanderbilt was forced to open the infield to the crowds. Even that hardly cleared things up. “The clubhouse was so mobbed,” writes Laura Hillenbrand, “that the NBC announcer Clem McCarthy couldn’t reach his post and was forced to call the race while perched on the track rail.”

The Pimlico Special itself was a race for the ages. At the break, Seabiscuit “uncorked the greatest burst of speed in his life”– opening a two-length lead on War Admiral. The Riddle colt rallied gallantly and pulled alongside him. Separated by a few inches, the two scorched down the backstretch and headed into the final turn. Both horses were going flat-out by the time they hit the homestretch. “Kurtsinger, who stated before the race that he never had had to ask War Admiral for his best, asked now,” wrote Bryan Field in The New York Times. “With all the power that has made him one of the country’s first-flight riders, he drove forward with War Admiral. Again and again [his] black-clad arm with the yellow bars rose and fell, but War Admiral could do no more. He had met a better horse.” In spite of the Mighty Atom’s best efforts, Seabiscuit drew away to win by four lengths– smashing the track record. He would later be voted the Horse of the Year.

Eleven days later, War Admiral came back to capture the Rhode Island Handicap by 2-1/2 lengths. He raced one more time in 1939– winning an allowance event at Hialeah– before incurring an ankle injury that forced Riddle to retire him to stud. The Mighty Atom closed out his career with $273,240 in earnings and twenty-one wins from twenty-six starts.

Impressively, War Admiral enjoyed the same level of success as a sire as he’d had on the track. His fillies generally seemed to outshine his colts. In 1945, he became the first Triple Crown winner to lead the general sire list– largely thanks to his daughter Busher. Over the course of the year, she won the Arlington Handicap, the Hollywood Derby, and numerous other stakes to rack up $273,735. Busher would ultimately be named the 1945 Horse of the Year, inducted into the Hall of Fame, and ranked the fortieth-best horse of the 20th century. She went on to become an accomplished broodmare and is the great-great-granddam of Seattle Slew.

Another one of War Admiral’s best daughters was Searching. After losing her first twenty starts, the filly was claimed by Hirsch Jacobs (the trainer of Stymie). Jacobs discovered she had tender feet, inserted felt between her hoofs and shoes, and transformed her into a star. Searching won twelve stakes races– including the Gallorette Stakes (twice), the Correction Handicap (twice), the Diana Handicap (twice). She was voted into the National Racing Hall of Fame in 1978. Searching is also the dam of three-time champion Affectionately.

In addition to Searching and Busher, War Admiral sired top performers like Blue Peter (the 1948 Champion Two-Year-Old Colt); Busanda (winner of the 1951 Suburban Handicap and the dam of Buckpasser); and Iron Maiden (first in the 1947 Del Mar Handicap and the granddam of Swaps). In a final testament to his ability as a sire, War Admiral appears in the pedigrees of both American Pharoah and Justify.

The Mighty Atom spent most of his remaining years at Sam Riddle’s Faraway Farm. Though Riddle died in 1951, the stallion stayed at the farm before being moved to Hamburg Place in 1958. The following year– after a “two-day illness”– War Admiral passed away. He initially was laid to rest between his parents at Faraway Farm. When their graves were moved to Kentucky Horse Park in the early 1970s, War Admiral was reburied at the foot of Man o’ War’s statue.