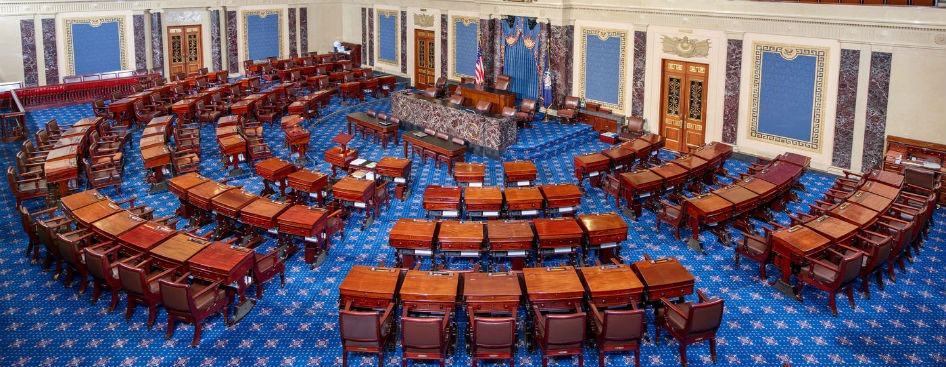

Even though the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act passed on a voice vote in the House of Representatives Tuesday, perhaps it’s still not too late to suggest expanding the Act’s coverage to include horse sales as well as races. Even after it passes the House, the legislation will join some 200-plus other bills on Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s desk, and there’s no telling when, or even if, it will come up for a vote in the Senate, despite McConnell’s recent public endorsement.

Over the years, buyers at thoroughbred sales have complained about horses that were bulked up on steroids for the auctions, then shrank by 100 pounds or more when they arrived at the buyer’s farm. Or buyers of two-year-olds were never sure exactly what sort of chemical help their purchases may have had to aid them in running a quarter-mile in under 21 seconds. Expansion of the new legislation to cover, at a minimum, two-year-old sales would provide a far more effective enforcement mechanism than exists under the current self-regulation by the sales companies.

Fasig-Tipton, Keeneland and the other auction companies publish their own “conditions of sale,” which principally define the circumstances under which a buyer can return a horse and get her money back if there’s something wrong. The dissatisfied buyer must, in order to return a horse, find some specific violation of the conditions. There’s explicitly no warranty that any horse bought at a sale is suitable for racing, nor is there any warranty of soundness or wind (breathing ability).

In the bad old days, prospective buyers would have to hire their own veterinarians to x-ray a potential purchase and “scope” it to check airway performance. Now, most sales consignors post a set of x-rays in the sales company repository, many post a scope as well, and buyers can’t return a horse for any defect that should have been seen if the buyer’s vet had looked at the repository information. Buyers will still do a detailed vet analysis of the horses they expect to go for a lot of money, including ultrasounds of the horse’s heart and other tests, but for many (most?) of the horses in a sale, they often rely on the one- or two-page vet report that the consignor will show them at the barn or at the back of the sales ring. I’ve seen a lot of those reports, and, guess what?, an astonishing number of young horses have an “A+” scope according to the seller’s vet, and hardly any have any issue that would raise a “material” concern about their racing soundness. In sales world, as in Lake Woebegon, all the children are above average.

The sales companies also have drug rules in. their conditions. They don’t permit anabolic steroids (the drugs that made certain baseball players look like the Michelin Man) or biophosphonates at all for young horses, nor do they allow clenbuterol or other broncho-dilators within 90 days of the sale, and horses on the sales grounds can be treated with only one NSAID painkiller (like Bute) and only one corticosteroid. And at the two-year-old sales, no drug at all are allowed in the 24 hours before a breeze. But enforcement of these rules is largely left up to the buyer. If a purchaser suspects there’s a drug issue, the purchaser can pay $500 up front for a drug test and then, if a prohibited drug is found, return the horse and get compensation. In addition to the drug prohibitions, the conditions of sale ban the use – but only while the horse is on the sales grounds – of shock wave treatment, buzzers (for two-year-old breezes), joint injections and other procedures that might mask breathing problems or lameness. But, again, enforcement is largely on the honor system or at the expense of a suspicious buyer.

These conditions, except for the ban on anabolic steroids and biophosphonates, don’t say much about what happens back at the farm, especially at the two-year-old training centers that prepare horses for those absurdly fast breezes. Generally, if a seller discloses surgery or some other abnormality (like the horse being a cribber), then it’s buyer beware. But if a rider at the farm uses a buzzer to habituate a horse to running faster than it would otherwise do, who’s to know? And if some prohibited drugs are used, but disappear from a horse’s system before the sale, who will enforce the ban? The new legislation provides for out-of-competition testing for race horses. Why not also do that testing at the two-year-old training centers?

Expanding the coverage of the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act to, at a minimum, cover two-year-old sales wouldn’t solve all sales issues. There would still, for example, be the problems of unscrupulous agents who take kickbacks from consignors, or agents and even sales company personnel who have hidden interests in the horses being sold, but it would send a signal that, from the time a horse starts preparing for a race track career, it’s going to be abiding by a uniform national drug regimen, and that those charged with the horse’s care will be subject to real enforcement, not just their presumed gentleman’s word.