In the first decade of the 20th century, one horse stood above the rest, only needing one word to comprise his iconic name: Colin. In his career, this son of Commando went undefeated, winning all fifteen of his starts at two and three. His wins in races like the Champagne, the Withers, and the Belmont Stakes helped make James R. Keene one of the leading owners in the world in 1907 and 1908. Colin was so good that his trainer James. G. Rowe said that he wanted his epitaph to read simply “He trained Colin.” Colin’s performances overshadowed those of his stablemate, Celt, winner of the 1907 Junior Championship Stakes and the 1908 Brooklyn Handicap. Also a son of Commando, Celt might not have beaten Colin on the racetrack, but was clearly Colin’s better in the breeding shed, making his historical impact on the sport of kings through his sons and daughters. One daughter in particular cemented Celt’s status as a sire of import in the 20th century.

Commando, sire of both Colin and Celt, was Hall of Fame sprinter Domino’s best son. He won the 1901 Belmont Stakes and nearly won the Lawrence Realization as well, breaking down just short of the race’s finish. Keene retired him to stand at his Castleton Stud, where Commando would go on to sire greats like Peter Pan, Colin, and Celt. Commando died in 1905, two years before Colin and Celt had their first starts, leaving both colts as valuable stud prospects once their racing careers were done. For Celt, Commando’s loss proved fortuitous since soundness became his biggest challenge.

While Colin would rack up twelve wins in twelve starts at age two, Celt managed to appear only twice. Scratched from his first two scheduled starts, the chestnut colt finally made his debut in September 1907 in the Flatbush Stakes – against his dominant stablemate. Colin took the lead early in the race and had no trouble holding off the rest of the field for a three-length win; Celt stayed off the pace with Bar None, easily passing that colt in the stretch to finish second. With Colin undefeated to that point in 1907, it is entirely possible that Celt was not driven to his best performance so that Colin could maintain his impeccable record.

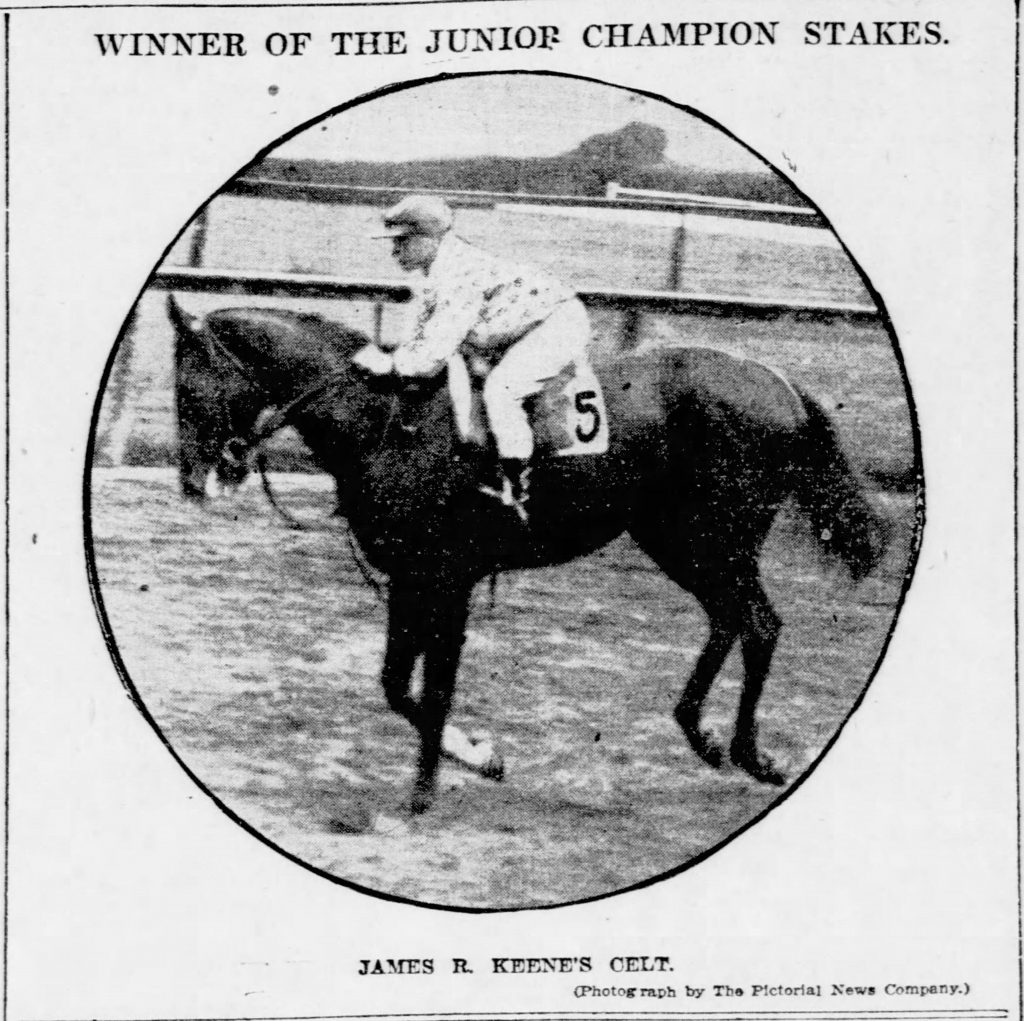

For his next start, Celt faced only three others in the Junior Championship Stakes at Gravesend Race Track. The race was structured as an allowance race, so, as a maiden, Celt got a break in the weights, carrying only 107 pounds. Also at 107 pounds was Uncle, a son of Star Shoot recently purchased from John E. Madden by trainer Sam Hildreth. Uncle ran on the lead for most of the six furlongs, with jockey Walter Miller keeping Celt just off the pace until the stretch. Miller drew Celt alongside Uncle, the two colts battling through that last furlong until finally Uncle’s speed gave out. Celt drew away to a length-and-a-half victory, covering the six furlongs in 1:10. Observers rated Celt as good as Colin, speculating that Celt could have beaten his stablemate given the opportunity. Rather, as 1907 gave way to 1908, Celt remained on the shelf, Keene preferring to send Colin in the bigger ticket races and reserving Celt for handicaps and weight-for-age events.

At three, while Colin was out dominating races like the Withers and the Belmont Stakes, Celt stayed mostly in the background. His first start came in late May; he faced only two others in the Jockey Club Weight-for-Age Stakes at Belmont Park. He won easily despite his long layoff, the beneficiary of lighter weight because of his few starts. Next, as trainer James G. Rowe, Sr. struggled with questions about Colin’s soundness, Celt joined two other star colts, Fair Play and King James, at the barrier for the Brooklyn Handicap.

Fair Play, who would later sire the great Man o’ War, had nearly caught Colin at the finish of the Belmont Stakes only two days before. King James, son of 1898 Kentucky Derby winner Plaudit, was trying to make a name for himself in the three-year-old division, but kept running into Colin and other great horses. For lightly raced Celt, both rated as credible threats to his chances at winning the mile-and-a-quarter Brooklyn. Yet, carrying the second highest weight in the field, Celt took the lead at the race’s start and left them all in the dust, winning the Brooklyn in track record time. He repelled all challengers, maintaining his lead easily and demonstrating why he was held in such regard even with a superstar stablemate. It would be the last time he would be seen under colors in 1908.

Like Colin, Celt wrestled with infirmities that kept him off the racetrack for much of the three seasons he raced. Keene shipped Colin to England in the hopes that the colt could recover from his bowed tendons and return to the races over there. For Celt, spreading a hoof after his Brooklyn Handicap victory prompted Keene to keep the colt closer to home, fearing that the colt would not stand up to the cross-ocean journey. Trainer Rowe decided to point Celt toward a try at a repeat victory in the Brooklyn Handicap in 1909. To get Celt ready, they entered him in a weight-for-age race at Belmont Park on May 27th. Carrying the highest weight in the race, Celt defeated two other horses by eight lengths. Six days later, he was back for the Brooklyn Handicap.

Facing King James again, Celt carried 127 pounds to King James’s 126, twenty more pounds than he had carried the year before. At the break, stablemate Restigouche sprinted out to the lead, with King James and Celt stalking behind him. In the final furlong, King James made his move, running down Restigouche and winning by a hard fought three-quarters of a length. Celt finished behind them, never a factor in the race. Afterward, the hoof issue returned and, despite Rowe’s efforts to get Celt back into form, the colt never faced the barrier again. He was retired to Castleton Stud, where he stood for a year before Keene leased him to Arthur Hancock’s Ellerslie Stud in Virginia.

James R. Keene decided to retire from breeding in 1911, selling Castleton Stud the same year. He died in January 1913, leaving his son Foxhall Keene in charge of the remaining Castleton breeding stock. Ultimately, the family opted to sell their horses, and, that September, Hancock bought Celt from the Keene dispersal sale for $25,000. Celt stood at Ellerslie for the rest of his life, siring 127 winners and 29 stakes winners from 196 foals. Dunboyne, winner of the 1918 Belmont Futurity, and Polka Dot, winner of the 1919 Coaching Club American Oaks, were two of his best.

Celt’s long-term impact on horse racing, though, comes from a mare that raced just one time, but went on to become a historic matriarch of the sport. By Celt out of Fairy Ray, Marguerite was such a lovely yearling that William Woodward, head of Belair Stud, bought her from Hancock at a Saratoga yearling sale. She made one start at age two, injuring her back and finishing last. When it was clear that she would never race again, Marguerite was retired to Hancock’s Claiborne Farm, where Woodward kept his mares, and bred to two marquee stallions, Wrack and Sir Gallahad III. Her cover with Wrack produced Petee-Wrack, who won the 1928 Travers Stakes and the 1929 Metropolitan Handicap. Her first cover with Sir Gallahad III produced Gallant Fox, America’s second Triple Crown winner. Gallant Fox went on to sire Omaha, who would win the third Triple Crown in 1935.

For all of the racing time lost to his troublesome feet, for all of the times he was overshadowed by his legendary stablemate Colin, Celt ranks as a stallion of historical import. As part of Hancock’s Ellerslie Stud, he produced a mare who went on to produce a Triple Crown winner, a horse nearly as great as Man o’ War, product of Colin’s and Celt’s rival Fair Play. Celt is another example of how great horses sometimes make their biggest impact on the sport off of the racetrack.