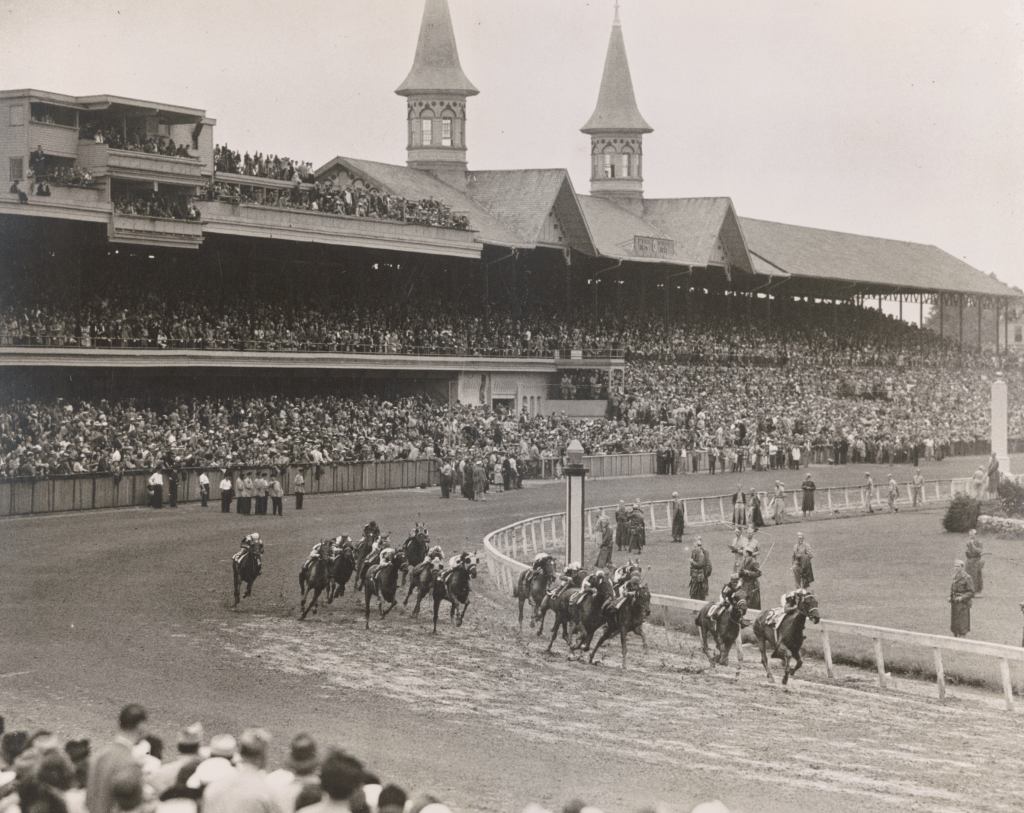

When the skies opened up during the week before the 1945 Kentucky Derby, the rain was perhaps a fitting commentary on the shortened Triple Crown season, a condensed celebration of tradition dictated by worldwide necessity. The war in Europe was over and racing, the only major sport that had been curtailed during the war, had returned from its temporary hiatus. While the European front had been resolved, uncertainty still reigned in the country: the war in Japan was an ever-present reminder that the fight was not over. Such was the 71st Kentucky Derby: gray grandness, traditional spectacle subdued by extraordinary circumstances.

For owner Fred Hooper, though, the day was anything but gray. On his first try, with his first Derby starter, this Southern contractor found himself in the vaunted Kentucky Derby winner’s circle, standing with the colt he had purchased for just over five figures only two years before. The plain brown package that was Hoop, Jr. made Fred Hooper a player in the horse racing game, a long way from his family’s cotton fields in northern Georgia.

Willing to Try, Willing to Buy

One thing about those of us involved with horses and horse racing is that we often are bitten by the bug early on and not always in the same ways. Fred W. Hooper, the fourth of ten children, decided at age fourteen to import some wild horses from Montana to Georgia and then broke all of them himself. He attended school through eighth grade and then took a quintessentially American meandering path through his early life that leaves one with the moniker a self-made man: he attended barber school and was the first chair the second day of work; taught high school in Georgia; farmed potatoes in Florida; and then, thanks to a ruined potato crop, borrowed money and tried his hand at a road construction contract, which lead to his own construction company. That company became one of the most successful in the Southeast.

With professional success assured, Hooper relocated to Montgomery, Alabama in the 1930s and bought 5,000 acres outside of the state capital. First, he raised cattle there, breeding Herefords, but saw potential in raising Thoroughbreds there too. He had built his skills as a horseman on the farm in his youth and knew what to look for in a racehorse too – he had had his own Royal Prince, a half-breed Thoroughbred that he won backwater match races with in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. By the early 1940s, Hooper decided to take the plunge and invest in bloodstock, heading up to a Keeneland sale with the intent of purchasing some fillies to race and then breed.

By 1943, when Hooper sat ringside considering horses to buy, Sir Gallahad III had built a reputation as the best sire of the era. Not only had he produced Gallant Fox, the second Triple Crown winner, but he also had sired Gallahadion, 1940 Kentucky Derby winner, and High Quest, 1934 Preakness Stakes winner, and more stakes winners on two continents. Hooper knew that Sir Gallahad III was getting older and decided to get in on the bloodlines of this leading sire and broodmare sire while he still could.

At that year’s Keeneland sale, he saw this colt bred by Robert Fairbairn, one of the initial investors in Sir Gallahad III, and liked the look of this yearling out of a mare named One Hour, a stakes-winning mare who already produced several stakes winners herself. “I just liked his walk, and his looks, and the smartness of his eyes and all,” Hooper said of the colt. When the gavel fell, Fred Hooper bought his first Thoroughbred for $10,200, a bargain considering the names that populated the colt’s pedigree. He named the bay colt Hoop, Jr., after his son, Fred W. Hooper, Jr., and sent the colt to former jockey turned trainer Ivan Parke to prepare him for the races.

Beginner’s Luck

Hoop, Jr. was not the only horse that Hooper bought that day – he also purchased another future stakes winner, Alabama, and three other yearlings – but, of that initial investment, Hoop, Jr. was like striking oil with the first thrust of the shovel. The colt won his first start, a three-furlong maiden race at Hialeah in late February 1944. He took the lead at the start, fended off the advances of Geronimo, and then finished with enough speed to win by a length. He finished second in his next two starts, both at four and a half furlongs at Pimlico, showing drive and speed in closing both times. He again came from off the pace in the Pimlico Nursery Stakes, but could not make up enough ground to catch Dockstader at the end.

Trainer Ivan Parke sent Hoop, Jr. to Suffolk for a five-furlong unnamed feature for two-year-olds. This time, he ran on the lead and dominated the race, winning by five over stablemate Pry. In five starts, this Sir Gallahad III colt had established himself as a horse to watch. His next start would take him to Chicago and Washington Park, but the colt never made it out west. Hoop, Jr. was showing signs of developing osselets, arthritic callouses that affected the front fetlocks. Continued racing could complicate the colt’s long-term soundness so Hooper opted to take Hoop, Jr. out of training for 1944. “Let’s put this colt away,” the owner told Parke, “and win the Kentucky Derby with him.” Hoop, Jr. went home to Alabama, turned out to rest and recover. The 1945 Kentucky Derby was almost eleven months away.

Hoop, Jr.’s nascent career was playing out against the backdrop of World War II’s waning days. When Hooper purchased the colt at a 1943 Keeneland yearling sale, the sale itself was a result of the cancellation of both racing and yearling sales at Saratoga. With transportation limited by the war effort, racing was centered in larger population areas, like New York City, and traditional racing milestones like the late summer season in upstate New York were suspended. By late 1944, though, the War Department had decided to curtail racing altogether, the only major sport asked to halt during the whole of World War II. Citing the distractions of racing and the resources it supposedly took away from the war effort, the Office of War Mobilization declared Thoroughbred racing halted effective January 3, 1945.

The Allies declared victory in the Battle of the Bulge in late January, finally breaking through Germany’s attempt to stop their march toward Berlin and victory in Europe. Their British allies continued racing throughout the war, even with the threat of German bombs raining down on the British isles. Meanwhile, back in the United States, racetracks were quiet and horses like Hoop, Jr., those waiting for the classic season and their own shot at the Triple Crown, were forced to stand idle and await their chance to get back to business. By the time the Germans and their allies surrendered in early May, it was too late for the traditional first Saturday in May. Instead, the Kentucky Derby had been rescheduled for June 9th, one month after racing resumed.

Hoop, Jr., idle for nearly a year, needed to get back on the Derby trail and had to do it fast. Trainer Ivan Parke sent the colt to Jamaica Race Track in New York, with the goal of the Wood Memorial as their big prep race on the way to Louisville. Hoop, Jr. faced a field of fourteen in a six-furlong tune-up at Jamaica, the Cedar Manor. Workouts leading up to this sprint had promised that the son of Sir Gallahad III was raring to go, on his toes and ready to run. The crowd made him the 7-10 choice over the field, which included other Derby potentials, but, after leading for the first part of the race, Hooper’s colt could not hold off his challengers, fading as the future Hall of Fame filly Gallorette passed him to win by three lengths. Hoop, Jr. finished fourth, his one and only out-of-the-money finish in his entire career.

Eight days later, Hoop, Jr. redeemed himself with a two and a half-length victory in a split Wood Memorial. With the Derby just over a week away, the 155 nominees for the race had to be narrowed down to a starting field and fast. Facing eight others in the Wood’s second division, Eddie Arcaro sent Hoop, Jr. to the lead and held it at every call, holding off Polynesian and Red Pixie to win by three lengths. With the Run for the Roses fast approaching, that Wood Memorial performance put Hoop, Jr. high on the list of Derby hopefuls. That two-time Kentucky Derby winner Eddie Arcaro took the mount on Hoop, Jr. for the big race demonstrated just how serious a chance Fred Hooper had at winning America’s biggest race with his first starter.

Splish Splash

The clouds hung around even after the rain stopped around 10 am on June 9th. Churchill Downs had stood idle for much of 1945, forced silent by war, but this was the Kentucky Derby and the grounds teemed with uniformed revelers despite the puddled ground underneath. The sun struggled to join them for the festivities, perhaps a reminder that while this particular party celebrated one victory, the war was not over yet.

For Hoop, Jr., today was his biggest test of all. He was second choice, Pot o’ Luck entering the gate with slightly shorter odds. There was a moment of hesitation that Hoop, Jr. would even be a part of it all: he had never run on an off track and Hooper wavered over the choice to send his colt or keep him in the barn. Arcaro knew something that Hooper did not though: “It’s Derby Day, you get one shot in your lifetime with one like that. You gotta run him,” the legendary jockey told the rookie owner.

When it came to go, Hooper told Arcaro, “When the gate opens, you be the first one out and I know you’ll be the first one home.”

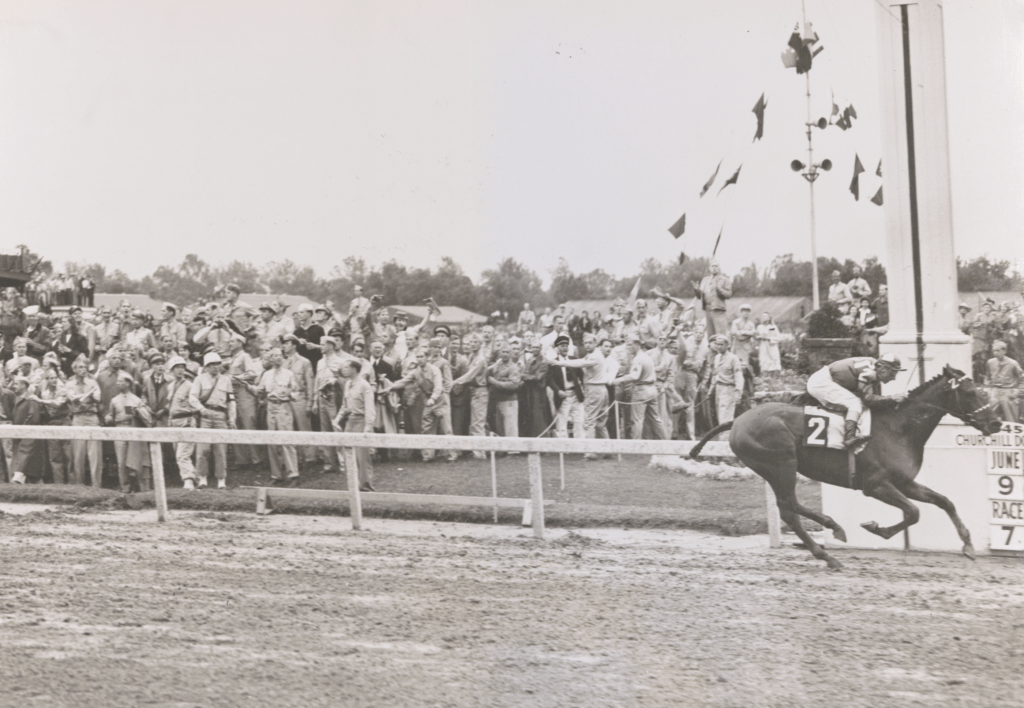

Breaking from post twelve, Hoop, Jr. started out toward the middle of the track, the best place to get traction in the fetlock-deep slop. Arcaro gunned the colt to the front of the field of sixteen, set the pace, and controlled the race from start to finish. Buymeabond got within a length or so of him on the first turn and Air Sailor on the final one, but Hoop, Jr. pulled away in the stretch, winning by six lengths. The trip was so smooth that Arcaro likened it to a rocking chair, only needing to tap the colt twice coming out of the gate. Hoop, Jr. did the rest.

Fred W. Hooper accepted the gold Kentucky Derby trophy from Governor Willis in the presentation stand and then cashed his $10,000 win ticket on his short-priced horse. The day netted him well over $100,000, far more than the initial investment of $10,200 at that fateful Keeneland sale. Hoop, Jr. ignited a fire that only returning to the Kentucky Derby winner’s circle could put out. Hooper would spend the rest of his life trying to win the Run for the Roses again.

Hoop, Jr. tried the Preakness Stakes a week later, but without Arcaro, who was in New York to ride Devil Diver in the Suburban Handicap. Jockey Al Snider was in the saddle for the Preakness, and seemed a poor substitute for the masterful Arcaro. Hoop, Jr. finished second, just ahead of Darby Dieppe on the rail while Polynesian won running out in the middle of the track. In explaining the Derby winner’s loss, Snider reported that Hoop, Jr. had crossed the finish line lame, struck by another horse while changing position in the stretch run. Hooper criticized Snider’s ride and denied that his colt was lame, promising that Arcaro would be back on Hoop, Jr. for the Belmont Stakes the following week. Neither happened.

Eddie Arcaro did win the 1945 Belmont Stakes, but on Pavot, not Hoop, Jr. The Derby winner, this bargain Sir Gallahad III foal, had bowed a tendon and was on the sidelines for the rest of 1945. Eventually, Hoop, Jr. was retired permanently, standing stud in Kentucky at Hagyard Farms and then moving to Circle H Farm in Alabama. When Fred Hooper established a large breeding operation outside of Ocala, Florida, he moved his 1945 Kentucky Derby winner there. Over his time at stud, Hoop, Jr. sired 113 foals, with seventy winners and three stakes winners. Hooper found even more success after that initial victory in Louisville, building on his small investment in 1943 to become an Eclipse Award winning breeder and leading owner over the next sixty years. Fred William Hooper passed away in 2000, far from the young man who had broken wild Montana horses at his family’s farm in the early years of the 20th century.

COVID-19 has changed the complexion of our Triple Crown season just as World War II did in 1945. While the season may not look the same, while the moments we hold dear are postponed or cancelled for hopefully just this year, we can look at Hoop, Jr. and his crew standing in the winner’s circle at Churchill Downs on a not-quite-May day and see that the sun will still shine on the Old Kentucky Home again, this time on a bright September day. And we will all rejoice in sharing that moment once again.

Photo Credit: The Keeneland Library