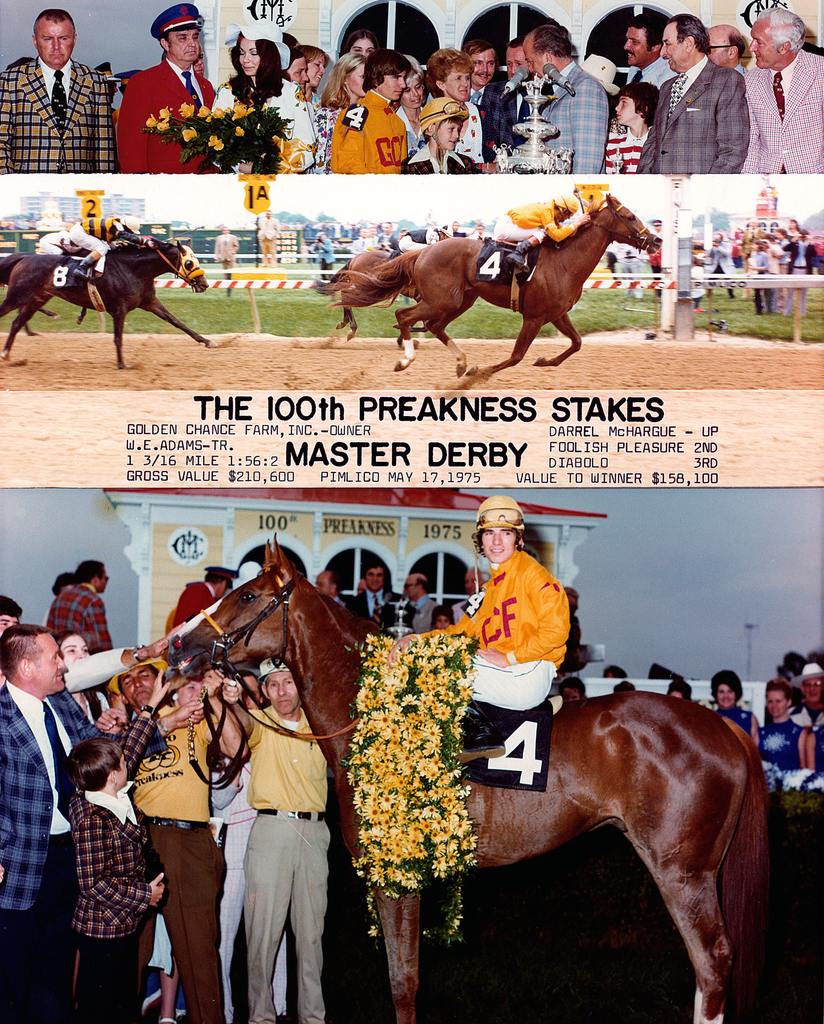

Master Derby pulling a Preakness upset over favored Foolish Pleasure (on the rail) with Diablo (#8) and Prince Thou Art (#2) hot on their heels. (Jim McCue/MJC)

Hall of Fame Jockey McHargue Rode Colt to Biggest Upset in Preakness History

David Joseph/Maryland Jockey Club

BALTIMORE, Md. – Unlike its Triple Crown counterparts, which each boast record win prices well into triple digits, the Preakness Stakes (G1) has historically been a race run true to form. In its first 147 years, including being split into two divisions in 1918, the Preakness has been won 73 times by favorites.

As much was expected in 1975, the Preakness’ 100th anniversary, when Foolish Pleasure arrived at historic Pimlico Race Course with a gaudy record of 11 wins from 12 races and exited a popular come-from-behind 1 ¾-length triumph in the Kentucky Derby (G1).

Among the rivals he passed on the way to the winner’s circle that day was Master Derby, a horse he beat by nearly seven lengths and would meet again in the Preakness – only with a much different result.

Sent off at odds of 23-1, Master Derby’s one-length victory over Foolish Pleasure still stands as the biggest upset in Preakness history. Returning $48.80, it surpassed the $45.60 Coventry paid as a 21-1 long shot 50 years earlier.

“I never really looked at that. I was just happy to be riding a horse like that in a race like that,” Master Derby’s jockey, Darrel McHargue, said. “I never was one much for really looking at what the toteboard said. That wasn’t one of my interests.

“I get asked about it occasionally, but most of the time it’s the distinction that you actually rode a Classic winner. That just stays with you,” he added. “I would like to have added a few more in there that didn’t pay quite so much.”

Master Derby was a son of 1970 Kentucky Derby winner Dust Commander, bred and owned by Robert Lehmann’s Golden Chance Stable and trained by William ‘Smiley’ Adams. After Lehmann died in January of 1974 at the age of 52, never having seen Master Derby’s rise to stardom, his widow, Verna, carried on the stable.

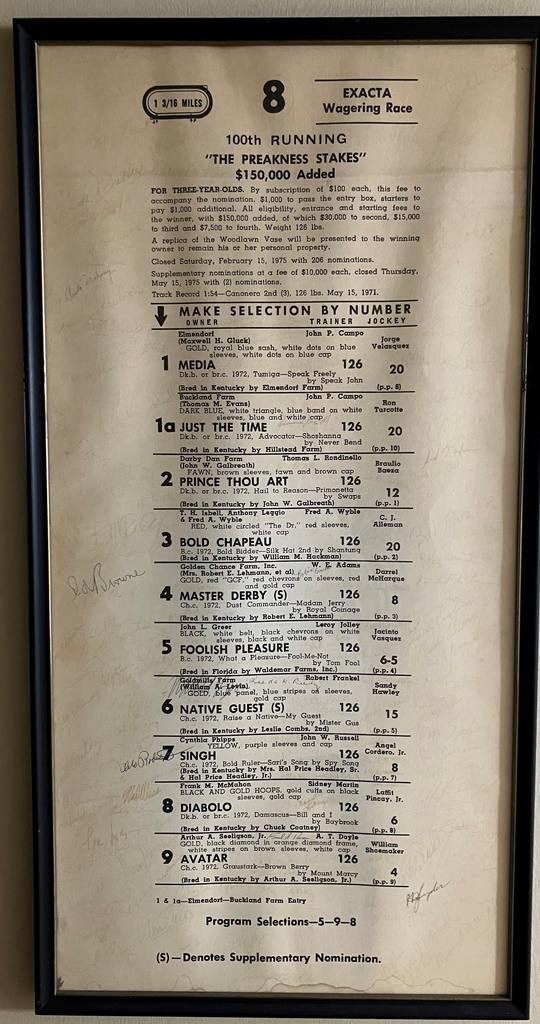

Ten 3-year-olds would line up for the 1975 Preakness, five of them at double-digit odds: Prince Thou Art (15-1), Master Derby, the John Campo-trained entry of Just the Time and Media (27-1) and Bold Chapeau (72-1). Foolish Pleasure, the champion 2-year-old colt of 1974 that would be inducted into racing’s Hall of Fame in 1995, was the 6-5 favorite.

Master Derby, who would break from Post 3, was given little chance of winning the Preakness despite a stellar record. A glorious chestnut with a bold blaze, he finished first or second in all 12 of his races as a juvenile with the Kindergarten (G3) and a division of the Dragoon (G3) at Liberty Bell among his victories.

As a 3-year-old, Master Derby began with a pair of sprint losses before winning the Louisiana Derby Trial Handicap (G2), now the Risen Star, over Fair Grounds rival Colonel Power and the Blue Grass (G1) in the slop at Keeneland with McHargue aboard. Back on a fast track for the Kentucky Derby, Master Derby could do no better than fourth.

“He was a very smart horse. Sitting in the gate, he would just be in there waiting for the gate to open and he was real easy to ride, because he was alert and more than willing whenever you wanted to use him,” McHargue said. “I thought he had a perfect trip in the Derby. In my mind, he didn’t have any excuses. But then Smiley Adams mentioned to me that he’d lost some time with him prior to the Derby and he thought he’d run a better race in the Preakness, and he did. He sure did.”

Adams had to convince Verna Lehmann to spend an extra $10,000 – the equivalent of $57,000 today – to supplement Master Derby to the Preakness, where he was made the co-fourth choice on the morning line at odds of 8-1. Also supplemented was speedy California invader Native Guest, undefeated in four career starts in California for future Hall of Fame trainer Bobby Frankel.

“Smiley Adams was a good horseman. He knew where his horses were, training-wise and fitness-wise, and he took care of his horses. He knew after the Derby. I said, ‘This horse didn’t have a straw in his path in the Derby. He had a perfect trip.’ He said, ‘I missed a little time with him. He’ll be better this time.’ And he was right,” McHargue said. “Now it might not be that big of a deal, but he had faith in him and he followed his beliefs. We all benefitted.”

Foolish Pleasure, trained by late Hall of Famer Leroy Jolley, drew the most attention coming into the Preakness, which drew a then-record crowd of 75,216. As expected, Native Guest went straight for the lead when the gates opened and put up fractions of :23 2/5 for the opening quarter-mile, followed closest by Media, Master Derby and Singh. Foolish Pleasure raced in seventh, behind Diabolo and Avatar, with Bold Chapeau and Prince Thou Art trailing the field.

Jockey Jorge Velasquez and Foolish Pleasure continued to save ground along the rail down the backstretch, waiting for the front-runners to tire, as the half-mile went in :47 1/5 and six furlongs in 1:11 1/5 with Native Guest still in front. McHargue and Master Derby were never more than two lengths away from the lead and had closed to within a head as the field came to the quarter pole.

At that point McHargue gave Master Derby his cue, and he responded with a surge to straighten for home with a three-length lead. Meanwhile, Velasquez had tipped Foolish Pleasure out around horses on the turn to make their run, not unlike the move they made to win the Derby but had less time to get there in the Preakness which, run at 1 3/16 miles, is a sixteenth of a mile shorter.

Velasquez set his sights on Master Derby, who began to drift outward in mid-stretch, and decided to duck back down to the inside to make a final bid that would come up a length short. Velasquez lodged an objection, claiming his forced late course change cost him, but the stewards ruled that Master Derby had a clear lead and the order of finish was unchanged.

“Our colt has had good luck before. He had it in the Wood Memorial and he had it in the Derby,” Jolley would tell Sports Illustrated. “Today it was somebody else’s turn. Sometimes you use up the good luck, and you’ve got to take a bit of the bad.”

The victory, worth $158,100 ($886,994 today), was the sixth in nine races to start his 3-year-old season, with the Derby being his worst finish in 21 lifetime starts. Foolish Pleasure held second by a length over Diabolo, with late-running Prince Thou Art fourth. Avatar, Singh, Native Guest, Bold Chapeau, Just the Time and Media completed the order of finish.

“I really think I kind of got the jump on [Foolish Pleasure] that day. Master Derby being as he was, he was just waiting for the time when you asked him to accelerate, and he did it instantly,” McHargue said. “He was a horse that was forwardly placed. He wasn’t necessarily on the lead, but he would just sit there and wait for you to give him a signal to go. When I did ask him, he really kicked in for all he was worth once they were coming in the stretch.

“He had a really fast turn of foot and rapid acceleration, so somebody would really have to be a better horse to beat him that day because he was well-trained, there was no fitness issues or anything like that. When he accelerated, I knew it would take a better horse to beat him because he was running his race that day. With a turn of foot like he had, you could really feel the acceleration beneath you,” he added. “I was glad to see the wire come, though.”

McHargue, still just 20 years old but a rising star who had won his first race barely three years prior, got the ultimate praise from Adams for what the media called a “cagey,” “cool” and “professional” ride.

“This jock here, he couldn’t have rode him no better than today,” Adams told the New York Times. “What more can I say?”

Aside from being his first, and as it turned out only, win in a Classic race, it was an especially memorable victory for McHargue, an Oklahoma City native that was the leading rider at nearby Laurel Park in 1973 with 67 wins.

“I had some connections at the time from Maryland, so it took on a greater significance. It was a different time in my life, but having had success in Maryland and being able to spend quite a bit of time there, it was a very special time for me,” he said. “That’s the thing. You go, ‘Oh my God, I won the Preakness.’ With all the people that are there and watching, it’s a great experience for a young rider. I was on the horse that captured the day.”

Ironically it was Velasquez, rider of the beaten favorite, that would ultimately put the Preakness win into perspective for McHargue.

“I really got a sense of it even moreso one night when we were coming home from racing and I was on the plane with Jorge Velasquez. Jorge Velasquez was a guy who was an artist at riding, with his style, and he was riding the best horses in the country,” McHargue said. “It was nighttime and we were flying back and he said to me, ‘What are you going to do now?’ And I said, ‘What do you mean?’ And he said, ‘Well, you’ve got to go somewhere. New York or California.’ I hadn’t really given it a whole lot of thought. I hadn’t given it any thought, really. I said, ‘Do you think I could make it there?’ And he said, ‘My God, you won the Preakness. Do you know what winning the Preakness means?’ That’s when it took on a whole new dimension. When I heard somebody of that caliber describing it that way, it really took on a higher place in my mind.”

Speaking to Kent Hollingsworth in Paris, Ky. two days after the Preakness, an interview contained in the archives of the Louis B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky, Verna Lehmann described what it was like to win the Middle Jewel of the Triple Crown.

“That phone’s been ringing all day long,” Lehmann said. “Bourbon County, I guess they went crazy here. I expected the telegrams and the telephone calls, but I wasn’t expecting the flowers, so that was very nice.”

Asked whether she put a few dollars down on her Preakness horse, Lehmann said: “I don’t bet on him. I had no reason why I don’t. It was tempting to put a bet on him when he went off at 23-1. I couldn’t believe it. I thought people just thought he couldn’t run on a fast track. But they were wrong.”

Master Derby would go on to run third in the Belmont Stakes (G1) and Ak-Sar-Ben Omaha Gold Cup (G3) at 3 and win the Whirlaway (now Mineshaft) Handicap, New Orleans Handicap (G3) and Oaklawn Handicap (G3) at 4 and also run second in the Met Mile (G1) and Trenton Handicap (G2) before being retired following a fifth-place finish as the favorite in the Ak-Sar-Ben Cornhusker Handicap (G3).

Overall, Master Derby raced 33 times with 16 wins, eight seconds, four thirds and $698,624 in purse earnings. He stood stud at Gainesway Farm near Lexington, Ky., where he sired 31 stakes winners before his death at age 27 in 1999.

McHargue’s riding career was short but brilliant. He won 2,553 between 1972 and 1988 with purse earnings of $39.6 million. In 1978 he won both the Eclipse Award as champion jockey and George Woolf Memorial Jockey Award as voted by his colleagues after setting a North American single-season earnings record of $6,188,353, breaking Steve Cauthen’s mark set just the year before.

McHargue won a career-best 405 races in 1974, second in North America behind Chris McCarron’s 546, beginning a six-year streak of ranking in the top 10 nationally in annual earnings. From 1976, when Equibase began compiling statistics, through 1988 he won 79 graded-stakes including six with Hall of Famer John Henry. McHargue won stakes on Hall of Famers Ancient Title and My Juliet and also rode such top horses as General Assembly, Run Dusty Run and Vigors.

The winner of six races on a single card at Santa Anita in 1978 and 1979, McHargue also tasted success internationally. During the 1980s he rode in both Ireland and England, where in 1984 his victories included the Irish St. Leger at the Curragh and the Jockey Club Cup at Ascot. In 2020, the Historic Review Committee voted McHargue into racing’s Hall of Fame. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, his induction was delayed until 2021.

“That was unbelievable and completely unexpected,” McHargue said. “I’m glad to be one that landed on a lucky star that day.”

Chief steward for the state of California since 2015, McHargue credits Master Derby with taking his riding career to the next level.

“He was a dream to ride. He was a very mature and intelligent horse with lots of ability. Sometimes his intelligence would give you the capability to be the better horse on the day because he didn’t do any silly stuff. He was always waiting for you and paying attention to you,” McHargue said. “As a 3-year-old he ran like a mature older horse. He didn’t make many mistakes. And he had a turn of foot that when you asked him, whether it was to go through a hole or whatever it was, he gave it to you right then.

“I always thought he made the most of his ability through his brains and thought process,” he added. “He stayed sound throughout his career and that’s a big thing. You don’t realize it early on, but horses that go through all those races and go through the 3-year-old campaign starting in February, March and April and getting all the way through the Belmont, those are hard races, all three of them. For a horse to do that, they have to be special individuals, soundness-wise, to even make it through.”