By BEN BAUGH

It may be the most difficult of all things to learn, patience, but it’s especially important if you’re a Thoroughbred trainer. It was a lesson Randy Bradshaw learned early on from his uncle, Thoroughbred conditioner, Lyman Rollins.

Family Ties

The high plains and Rocky Mountains provided an idyllic landscape for Bradshaw to grow up in. His family had a ranch in Wyoming, and his father had a great passion for racing. But it was his uncle’s influence that would resonate deeply within the horseman, learning lessons that are still part of his daily routine to this day.

When Bradshaw’s father decided to get into the Thoroughbred business, he purchased 10 broodmares and one stallion from his uncle and one of his clients.

“So, we started breeding horses in Wyoming,” said Bradshaw. “But there weren’t a whole lot of people who want to buy racehorses in Wyoming. We actually did cutter races and things like that back then which was a lot of fun.”

However, the foundation that was being laid would be critical, and from those nascent stages, Bradshaw’s talent as a horseman would continue to evolve. The family would relocate to Utah, where the market for Thoroughbreds was a bit better than Wyoming, but not markedly.

“We probably had eight or 10 babies; and we’d break some of those, and when Lyman came through going to Centennial and places, he’d buy a few from us or take a few over there to train, and that’s when I was about eight,” said Bradshaw.

Growing Bolder

As he got older, he became more involved with the horses’ training, his ability as a horseman continued to progress, and he would grow in confidence.

“When I got to be about 14 or 15, I began galloping horses,” said Bradshaw. “I decided that I wanted to ride a few races, just stuff around Utah, Idaho and Nevada. So, we got there, started to sell a few horses and raced a few.”

An Extreme Departure

But the vagaries of life would soon find Bradshaw in a completely different environment.

“I got drafted into the Army, and did a stint for a couple of years and went to Vietnam,” said Bradshaw. “When I came back from Vietnam, I did a few things. My ex-wife’s father owned a carpet store, so I started laying carpet and learned how to do that. And I finally decided that’s not what I wanted to do.”

A strong sense of knowing one’s self

Bradshaw would answer his calling, returning to the vocation that was firmly a part of who he was. He called his uncle, Lyman Rollins, and returned to his former way of life. He found himself living in a 25-foot travel trailer with his ex-wife Debbie and their daughter Alycia (Debbie is also the mother of Bradshaw’s twin sons).

“I went down and worked for him, travelled all over, going to Omaha, Denver and Phoenix in the winter,” said Bradshaw. “I stayed with him for about three years. He is without a doubt one of the most accomplished horsemen and patient guys that I was ever around. This business is all about patience. If you want to get in a hurry, it’s not going to work. If you want to take your time and do things the right way, you’re probably going to be more successful than most that don’t.”

It was during his first year at Ak-Sar-Ben while working for his uncle, that Bradshaw was approached by a Hall of Fame trainer.

“(Jack) Van Berg offered me a job,” said Bradshaw. “I thought that was the greatest thing ever.”

Early challenges

Eventually, nearly three years later, Bradshaw would hang his own shingle outside his barn, but it was less than an easy transition, experiencing the challenges associated with being in business for one’s self.

”I was literally charging one guy about $8 a day to train his horse, one that I got from Utah, when I should have been charging him $25 to $30 a day, and trying to make a living off of that was tough,” said Bradshaw.

Lighting fast

But fate and the vagaries of life would show themselves in a propitious nature, one that would introduce the world to a speedball, a horse of tremendous turn of foot that would help establish Bradshaw’s reputation as a premier conditioner.

“I got a really good horse called Petro D. Jay,” said Bradshaw. “He ended up equaling the world record for three-quarters of a mile, when it was 1:07 1/5. He was a very fast horse. I took him to California and he set three tracks records. He was such a good horse, we started going to southern California, and I began taking a string over there. There was a guy that my uncle actually trained for, for a while, Tom Caldwell. He was the head auctioneer at Keeneland. His two sons, Scott and Chris, were also auctioneers. Chris just died last year. Scott is still there, and is one of the head auctioneers at Keeneland. That family kind of got me started, and gave me about 10 or 12 horses. I still went to Phoenix in the winter and came back to California in the summer.”

Petro D. Jay was a big black horse, who was lightning fast with no pedigree to speak of, said Bradshaw. Bud Coleman, who was from Nebraska and came to Arizona for the winter, had owned Petro D. Jay, before Bradshaw purchased the gelding for $50,000 for a client of his in Wyoming.

“He broke his maiden his first time out at Fonner Park, and then in the next race, he didn’t finish, he bolted, so the guy gelded him,” said Bradshaw. “He brought him to Phoenix for the winter, ran him one time. His first time out, he ran like 1:08.3 and he was second. We heard that the guy wanted to sell him.”

At that time, there wasn’t a lot of money for sprinters, but propitious circumstances and racing luck were once again on Bradshaw’s side. Corey Johnson, the former general manager at Turf Paradise, and one of Bradshaw’s best friends, was able to secure a $100,000 race for sprinters.

“And the next time, I ran him and he ran 1:07.2 (for six furlongs), and the time after that he ran 1:07.1 and equaled the world record,” said Bradshaw. “We had a lot of fun with him. My ex-wife Alicia and I sat under him every day; iced him every day and rubbed on him for hours on his legs. I’ve been around a lot of fast horses, and he’s the fastest horse I’ve ever been around.”

The only horse that Bradshaw thought may have been faster than Petro D. Jay was the Laurie Anderson conditioned Chinook Pass, the 1983 Eclipse Award winning sprinter.

“He (Chinook Pass) was a terrifically fast horse,” said Bradshaw. “Zany Tactics was fast, my friend Blake (Heap) trained him, but for sheer speed, out of the gate, for the first two or three jumps, they would be in front, but he was the best turn running horse I’ve ever seen.”

Petro D. Jay’s turn of foot was so fast, even those who had the privilege to ride him marveled at how easy he made things look.

“He was coming back off a layoff one time, and I had a kid named Les Hulet (the jockey), who was an old Utah boy who would come to Phoenix for the winter, get up and ride him,” said Bradshaw. “I said, ‘Les this horse is extremely fast, be careful. For the first half mile, I just want to go as easy as you can get him to go for a fast horse. He went 44.1 that morning in a half mile work. He came back. I said, ‘how fast do you think he went?’ He said,’ probably about 48 (seconds).’ He was an extremely quick horse.”

A growing reputation

Bradshaw began to enjoy the fruits of his labor, winning races and gaining entry into arguably the most competitive racing circuit in the country.

“We did pretty well with the horses we got from Tom Caldwell and his wife Mary,” said Bradshaw. “It started picking up, and we got more horses, more Cal-breds. I probably got up to about 20 or 25 head, but I always thought, ‘if I’m going to be successful, I need to go work for somebody else.’”

Knocking on doors

And he would ask arguably the highest profile trainer in the country, if he could join his operation, and this would be where the lesson he learned from his uncle would come in very handy.

“It took me about six months,” said Bradshaw. “I talked to Wayne (Lukas), and Wayne said, ‘Look, wait until Del Mar is over, and we’ll see if we can fit you in. I’m going to put you on.’”

The opportunity would finally present itself, and Bradshaw would find himself relocating to the upper Midwest.

“But after four or five months of going back and forth with him, he finally said, ‘We’re going to send a string to Canterbury Downs.’ I think it was the second year Canterbury was open. He sent me there with 25 to 30 horses. I ended up being the third leading trainer. It was a great experience.”

From there, Bradshaw would go to Keeneland, providing him with the opportunity to meet people in the Midwest.

“I eventually ended up at Oaklawn Park, went to Churchill Downs, Keeneland, Turfway Park; I moved five or six times a year,” said Bradshaw. “I would go to New York in the winter to give Kiaran McLaughlin a little break, give him a vacation, and then I would come back to California for the winter. It was a lot of moving and eventually you get a little tired of that.”

The right place at the right time

However, the experiences while working for Lukas were incredible and the opportunities provided Bradshaw with a number of indelible memories that have resonated powerfully throughout his life.

“It was probably one of the greatest times in my career just because you got to be around a lot of really good horses,” said Bradshaw. “I had Winning Colors for a while. I had Lady’s Secret for a while. Every good horse (from the Lukas barn) at one time was with me, between California and all of the other places we went. Working for Wayne, he’s so meticulous, everything is right down to the fine hair. His son, Jeff, was a little tough to work for, but he was one of the sharpest, smartest horsemen I’ve ever met.”

Jeff Lukas’ work ethic, strategic and logistical planning were without comparison. His dedication and commitment to Team Lukas was immeasurable, and his impact was felt throughout the entire organization.

“If the horses were going to stakes, he was the guy who mapped out the schedules for all the horses,” said Bradshaw. “He was good at it. If I worked a horse at Oaklawn Park in the morning, and he worked a little too fast, you could believe you were going to get a phone call because he followed the works in every division. He knew everything about every horse we had. Sometimes, it was tough working with Jeff, but Wayne and I have such a great association. I still break and train horses for him to this day.”

Leap of Faith

The experiences with Team Lukas, provided Bradshaw with a deeper foundation, and with a reinvigorated spirit, new connections and opportunities on the horizon, he went out on his own again. But prior to returning to training he decided to go in a different direction.

“After I left Wayne, I quit for a year and went to Idaho,” said Bradshaw. “I have a friend who had a tree spade business. So, I went out there, and I had my sons (twins, Lance and Brett) with me, and we spaded trees that one summer. Going into the fall, we didn’t have a whole lot of money.”

But propitious circumstances would prevail, and well-placed timing was a critical component in Bradshaw’s continued success.

“I got a call from Gary West, and he said, ‘Hey, the gal who worked for Gene Klein said that you’re one of the best horsemen that she’s seen, and I want you to go to work for me,’” said Bradshaw. “We made a deal, and I went back to Southern California. He sent me 12 horses including Rockamundo (winner of the Grade 2 Arkansas Derby), he was kind of over the hill by then, but it worked out. I had some pretty good clients, and we did real well,” said Bradshaw. “Everest Stables, the Siegels, Gary and Mary West (were among his clients). I probably was buying 35 babies a year for the Siegels.”

It was during this time, Bradshaw would pick up a Maryland-bred filly, by Citidancer, out of the Pleasant Colony broodmare Dumfries Pleasure. The dark bay filly Urbane, would score five of her nine victories while being conditioned by the horseman, who only a short time earlier had been spading trees in Idaho.

Urbane had previously been in the barn of Brian Mayberry, but continued her ascent in Bradshaw’s barn, winning her first start for her trainer convincingly in the Maryland Million Oaks at Laurel Park by an authoritative 8-lengths during her sophomore campaign. She would continue to flourish scoring added money wins in the Los Altos Handicap at Bay Meadows; the Geisha Handicap at Pimlico; the Delaware Park Handicap (Gr.3) and the John A. Morris Handicap (Gr. 1) at Saratoga. The stakes wins at Delaware Park and Saratoga were in consecutive starts.

“She was a very talented filly,” said Bradshaw. “The funny story was, the first time they ran her; they dropped her into a maiden $50,000. I had a client, Gary (West), and he was going to buy her. But my assistant at Hollywood Park had gone on vacation, and I couldn’t be in two places at once, so I let it go. And the thing worked out well. I told Samantha (Siegel) the story later that we were going to claim her. So, anyway they gave her to me to train. That association was very good. I went a lot of places with her (Urbane).”

It was while he was conditioning Urbane, that Bradshaw would welcome a new owner to his barn. One of the horses that he campaigned in the silks of that owner, would win the Santa Catalina Stakes (Gr.3) by 5 ½ lengths and the San Felipe Stakes (Gr. 2) defeating dual Classic winner Real Quiet by a head. Hall of Fame jockey Chris McCarron was up on the son of Marquetry in both victories. The dark bay would also start in the Kentucky Derby. The colt’s name was Artax.

“I picked up Ernie Paragallo at that time,” said Bradshaw. “I schooled him (Artax) on Oaks day before he ran in the Derby. Most horses would have been a little nervous. There are 1,200 people there on Oaks day, and that horse just went in there, cocked his hip and stood there like it was no big deal. He was the coolest horse.”

Change of Pace

His operation grew to about having 100 head in training in southern California, but the daily grind began to take its toll, said Bradshaw. But once again, life’s vagaries and good fortune seemed to be on his side.

“I just got a little burned out,” said Bradshaw. “Wayne called me one day, and said, ‘I just picked up Satish Sanan. I would really like for you to come back to work for me. I really need a top assistant.’ I talked to my wife, and I said, ‘This is probably a really good deal.’”

Bradshaw would return to Team Lukas at the Hollywood Park meet, and would enjoy immediate success, winning with six first time starters.

“Satish spent a lot of money, we had a lot of good horses,” said Bradshaw.

One of those horses was a daughter of Storm Cat, out of the Valid Appeal mare Nannerl, campaigned by Sanan’s Padua Stables and Joseph Iracane. Magicalmysterycat won four consecutive races as a juvenile, including three stakes wins, the Cinderella Stakes, Landaluce Stakes (Gr. 2) and Schuylerville Stakes at Saratoga (Gr. 2). She would later add the Valley Stream Stakes at Aqueduct in the fall.

Life on the Farm

But life is constantly transforming, and two years later, Lukas and Sanan would end their association, but relationships that were formed continued to grow and flourish, and Bradshaw again would find himself in a unique position.

“Satish called me one day, and said, ‘I’m going to make a change with the guy that we have down here. I’d like you to come to work down here (Padua Stables, Summerfield, Fla.).’ So, I made a deal with him and started breaking babies. It’s probably the prettiest farm in all of Florida. It’s an absolutely stunning farm. So, I went to work there for about three years.”

Among the horses broken and trained by Bradshaw at Padua, was the 2002 Breeders’ Cup Juvenile winner Vindication, who was campaigned by Sanan. The dark bay colt by Seattle Slew out of the Strawberry Road (AUS) mare Strawberry Reason, won all four of his career starts.

Training Transition

A career with continued success, a reputation for excellence and results that spoke volumes caught the attention of one of the most prominent names in the Thoroughbred industry, someone who had played a role in transforming the sport.

“I got a phone call from Frank Stronach one day, he said, ‘Hey, I like the things that you’ve done. I’d like you to come to work for me.’ He made me a really good deal. They (Adena Springs South) started doing a few 2-year-old sales, and I got in on that. He paid me a certain percentage of what we sold, a percentage of earnings of what the racehorses made, a pretty good salary, built me a house to live in, so it was a pretty good deal.”

Among the horses broken and trained by Bradshaw while he was at Adena Springs included the Canadian Horse of the Year Fatal Bullet, and Grade One winners Ginger Punch, Ginger Brew and Sugar Swirl.

“We were breaking about 300 yearlings a year,” said Bradshaw. “We had 600 or 700 broodmares on the farm.”

A new opportunity

But a change in direction that saw Bradshaw working at Adena Spring for more than a half decade, found Stronach downsizing his operation, with Bradshaw leasing stalls at facility in north Marion County, Fla.

“Luckily, the year before, he (Stronach) said, “I’d like you to bring up some of your old clients and pay stall rent.’ And I said, ‘Okay, I think I can do that.’ So, I called Mary Lou Whitney and John Hendrickson, and I said, ‘I’m going to train some horses for Frank. It was the perfect opportunity because I had already picked up my other clients.”

A good year for the roses

One of the horses broken and trained by Bradshaw for his clients at Adena Springs, was bred by Barry Irwin’s Team Valor. The son of Leroidesanimaux (BRZ), out of the Acatenango (GER) mare Dalcia (GER), was a chestnut colt by the name of Animal Kingdom, who went onto win the 2011 Kentucky Derby while in the barn of Graham Motion.

“Animal Kingdom was tough, he was tough to get to the gate,” said Bradshaw. “He didn’t break well. He was a little bit resentful about everything he did. He had a little bit of a different attitude.”

There’s no race like the Run for the Roses, but when Animal Kingdom went postward, Bradshaw wasn’t anywhere near Churchill Downs.

‘There’s a lady that lives not too far from here (his current locale in Williston, Fla.),” said Bradshaw. “She’s 90-some years old (now) and raises champion Whippet dogs. So, we came over to her house, watched the Derby, and saw Animal Kingdom win. To break a Derby horse is pretty special, to have one that good. There’s nothing better than the Kentucky Derby, it’s just special.”

What might have been

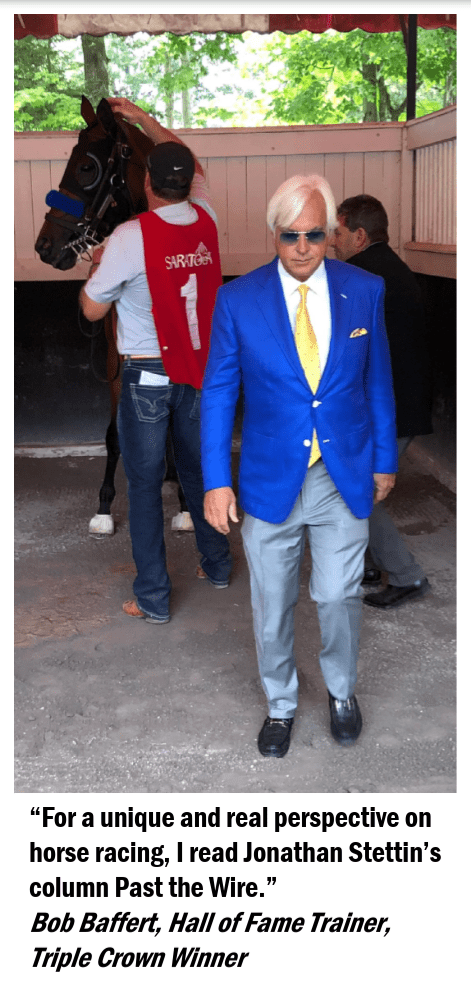

One horse Bradshaw thought had great promise, and could have won the 2017 Kentucky Derby, was a dark bay colt named Mastery. Campaigned by Cheyenne Stables, Mastery was undefeated with two stakes scores as a juvenile, winning the Bob Hope Stakes at Del Mar (Gr.3) and the Los Alamitos Cash Call Futurity (Gr.1). The Bob Baffert charge followed those added money wins with a victory in the San Felipe Stakes (Gr.2) at Santa Anita during his sophomore campaign.

“I think he would have won the Derby that year, he was undefeated and dominating everybody,” said Bradshaw.

And then another horse would emerge from Bradshaw’s program, a colt by Blame out of the Pulpit mare Ascending Angel. Nadal was bred by Sierra Farm and like Mastery seemed poised for greatness. He would win one of the divisions of the Grade One Arkansas Derby in 2020.

“I bought Nadal off of one of my favorite clients in southern California, a guy named Ed Hudon, from him and his wife Sharon,” said Bradshaw. “Ed died the day before I bought Nadal. Mike, the guy who runs the farm for the Hudons kept telling me, ‘Randy I can’t get this horse tired in the swimming pool. He was a big heavy horse, bigger than I like. But I thought, ‘Maybe we should go and try to buy him.’ I ended up buying him for $65,000. I sold him for $700,000, and he did well.”

The Sweet Smell of Success

A Hard Spun filly, out of the Came Home broodmare My Mammy, bred by the William M. Backer Revocable Trust, gave Bradshaw another Grade One winner. Outforaspin, was owned by the partnership of Commonwealth Stable, Randy Bradshaw and Stonestreet Stable, and was conditioned by another former Team Lukas assistant, Dallas Stewart.

The Virginia-bred chestnut filly captured the 2019 Keeneland Central Bank Ashland Stakes (Gr. 1), and retired with earnings of $392,363.

“I bought her for $70,000, and we sold her for $2.1 Million after she won the Ashland,” said Bradshaw. “We’ve been very fortunate to have some really nice horses that we’ve sold, and then get to follow their careers. That’s the fun part about my job.”

Quality of Life

However, horses aren’t self-existing items, and the daily routine of being in the barn every day can take its toll, said Bradshaw. But life at the training center suits the horseman well.

“I used to get up at 3 a.m., be at the barn at 4 a.m., and eventually, I don’t care who you are, it’s gets to be a job,” said Bradshaw. “The farm thing has actually worked out well. I have a lot of great clients and I get to train a lot of top horses, and then send them to old friends, like Todd Pletcher. Todd was a groom for me one year at Oaklawn Park. I still get the excitement of watching them run and do well.”

Bradshaw and his wife Sandy now have a 100-acre farm and 140 stalls in Williston, Fla., it’s the old Scanlon Training Center, where he shares only the training track with Hidden Brook South (Mark Roberts).

“Hidden Brook and I were looking for a place to buy, and luckily this place came on the market,” said Bradshaw. “This kind of fit the bill. It was close to where we worked, Frank’s place. And we ended up buying this place. Hidden Brook has the backside and we have the frontside. The only thing we have together is the racetrack. So, we maintain that together, which saves money.”

Late Developers

But not every racing prospect enjoys the same type of interest from buyers when consigned at the sales, it’s as if they have to overcome hurdles and climb mountains before they catch someone’s eye.

“I had a horse in Saratoga last year (2019), one that I had in two sales, and I told everybody I really liked this horse,” said Bradshaw. “I couldn’t get anybody to buy this horse, even though he worked well enough. We get up to Saratoga, and he ran second in probably the toughest maiden race they had last summer, to one of Steve Asmussen’s horses. He went to Belmont, and I had eight people calling me trying to buy him. So, we priced him at $1.2 million. We paid $200,000 for him. The race was such a tough race. Chad had one in there worth $1.4 million. It was a who’s who kind of field, so we went ahead and made the deal, and I thought were over the top asking $1.2 million. We sold three quarters of him for $700,000, and kept the rest.

“I make a decent living training horses for clients; who go to the racetrack, but I make more money buying these things and selling them.”

At home anywhere

A dark bay Kentucky-bred colt by Seeking the Gold, out of the Wavering Monarch broodmare Vana Turns, was a Bradshaw charge that demonstrated his tenacity and determination on the racetrack. Petionville was bred by Glencrest Farm and campaigned by Everest Stables and would go onto win five stakes races and earn $811,905. He would go onto to win the 1995 San Miguel Stakes in his second start by 2 ¼ lengths with Chris Antley in the irons. His added money scores included the Gold Rush Stakes in his third start with Russell Baze up, winning by three lengths, and then capturing his fourth consecutive race by a neck in the Grade Three Louisiana Derby, again with Antley up. The well-traveled colt later that spring would capture the Ohio Derby (Gr. 2) with Pat Day in the irons, holding off Dazzling Falls by a head. And later that summer Petionville would add to his impressive resume, with a win in the La Jolla Handicap (Gr.3) at Del Mar, this time with Corey Nakatani piloting the son of Seeking the Gold to victory.

“He wasn’t very big,” said Bradshaw. “When I started working him that year, they had Larry the Legend out there and bunch of horses in California, and he beat Larry the Legend his first time out. I had been around a lot of top Derby horses with Wayne, and I didn’t think he was quite that good, but he ended up being a pretty good horse. He was one of those neat little horses you just loved to take places because every place you took him was like home. I put him in a stall and that was home for him. He wasn’t a horse that was nervous or fretted about anything.

“Petionville and Artax were so easy. When you go into saddle them, they’re not one of those horses that are going in there and trying to get you upside down, be silly and stupid or wash out. They just walk in, cock a hip and let you saddle them, and away you go. Those horses were really a lot of fun, and cool to have.”

Slow and Steady

Patience is a critical component and sometimes with horses just as with people, it takes a while for them to develop, and that was just the case with a dark bay son of Grand Slam, out of the Cure the Blues broodmare Beckys Shirt. Cajun Beat would go onto win the Breeders’ Cup Sprint (Gr. 1), but didn’t demonstrate the talent he would showcase during his sophomore campaign early on in his career.

“He was an RNA at Taylor Made, so they asked us to come out to the farm, Bruce Hill and I went out there, and I think we ended up buying two or three horses out of that consignment, and Cajun Beat was one of them. We got him broke and we sent him to Benny Perkins Jr. at Monmouth. Benny had him for a while and he called me one day and said, ‘Hey, this horse has a little chip in his ankle, Randy, he can’t run, he’s not much stock.’ I said, ‘Okay, send him home. “

Bradshaw sent Cajun Beat to Cam Gambolatti at Calder, and the eventual four-time stakes winner began to show the promise the trainer had seen in him all along. Cajun Beat scored wins in the Hallandale Beach Stakes, the Kentucky Cup Sprint Stakes (Gr. 3) and Breeders’ Cup Sprint (Gr. 1) at age three, and would capture the Mr. Prospector Stakes as a 4-year-old.

“Cam’s telling me ‘This horse can run a little bit, he’s okay,’” said Bradshaw. “And then, he started winning stakes. It’s just funny how things go. I always tell people, you never want to discount one those horses early in their life. For me, I’ve seen too many horses develop and get good as they went along.”

Staying together

Familial ties and loyalty are welcomed and valued attributes. Bradshaw has been fortunate to retain many of the clients he worked with for years. The Hyder family, who campaigned Answer Do, trained by Bradshaw’s uncle Lyman Rollins, are among the owners Bradshaw still trains horses for.

Lyman Rollins conditioned another multiple stakes winner, a mare who still resonates powerfully with Bradshaw, named Bersid, who was a champion filly at Ak-Sar-Ben and won the Grade 3 Ak-Sar-Ben Queen’s Handicap, and enjoyed success everywhere she went.

“She was a great filly,” said Bradshaw. “I used to gallop her all the time for him. He would come to California, to my barn, and I would train her all the time. The minute I came around, and Lyman was sitting on the pony, she would pull right up. She knew right where the pony was. She was a cool filly that could really run. Lyman more than anything else, was a hay, oats and water guy, maybe some Red Cell, that was the only vitamin he fed and alfalfa. His horses always looked heavy and fat, carried a lot of weight, and looked good when he trained them.”

A Lasting Impression

The opportunity to learn from a trainer, who was respected and admired by his peers, left an indelible impression and provided a solid foundation for Bradshaw, one that has played a prominent role in his own training program.

“He was the most patient guy I’ve ever seen,” said Bradshaw. “If it took a week for us to get a horse onto a trailer, he’d take a week. That was just the way he was. He’d feed them a little oats and get them to walk a few steps. I learned everything about patience from Lyman. If a horse had a little filling in an ankle and needed time off, they got time off. And every year when they came home, they got turned out. After we went to Ak-Sar-Ben, we would go to Centennial, and then we would go back to Phoenix. They got turned out for two or three months, and those horses lasted a long time. He’s a guy that had about as good of an eye that I’ve ever been around. He would go to a sale, buy a horse for $4 or $5,000 and make stakes winners out of them. He was good at it.”

Being around the best

Propitious opportunities have also played a role in Bradshaw’s success. The experiences he’s had in the business have been an invaluable resource, providing him with an incredible amount of depth and understanding of the industry and its different facets.

“Between Lyman and being with Wayne, at the sales, I learned a lot about buying horses and trying to find good ones,” said Bradshaw. “I got a great education, something you can’t buy.”

The right fit

When Hall of Fame jockey, the late Chris Antley came to California, Bradshaw played a role in his resurgence. He began providing the jockey who had won the 1991 Kentucky Derby on Strike the Gold, with a number of mounts. He would win a second Run for the Roses on a chestnut colt by Summer Squall out of the Drone broodmare Bali Babe.

“I had a string in California for Wayne, and I started riding Chris, and he was winning races for us,” said Bradshaw. “Wayne came into town, and Chris won a race for us, and we were walking back under the tunnel at Santa Anita, and Wayne goes, ‘Man, we need to find a rider for Charismatic.’ And I said, ‘What about Chris? He’s hungry, he’s won a Derby. Why don’t we give him a shot?’ He (Wayne) said, ‘I’m going to talk to his agent.’ He went right down to the jock’s room to talk to the agent, and that’s how Chris Antley got the job.”

Antley was one of the most talented riders Bradshaw had ever seen, and was impressed with the horseman despite the problems that had plagued his life throughout his outstanding career.

“He had some personal demons that he couldn’t overcome,” said Bradshaw. “He was a great kid to be around. He was very smart and articulate. He had his Ant Man stock market thing going, and that was making money, but it was sad the way his life ended because he was so talented.”

Charismatic would go onto score wins in three consecutive stakes races, the Coolmore Lexington Stakes (Gr. 2), the Kentucky Derby (Gr.1) and Preakness (Gr. 1), before a third place finish in the Belmont Stakes (Gr.1), a race where the chestnut colt broke down, and Chris Antley’s quick thinking played a role in saving Charismatic’s life.

“I really thought we had a huge shot to win the Triple Crown, which would have been maybe a final feather for Wayne because he’s probably not going to get those kind of horses very often anymore,” said Bradshaw.

Jersey Girl

A New Jersey-bred filly, who would reel off 10 straight stakes victories, including winning New York’s Triple Tiara, would pass through Bradshaw’s hands. Open Mind, was a chestnut filly by Deputy Minister out of the Stage Door Johnny mare Stage Luck. Bred by Due Process Stable, she raced in the silks of Eugene V. Klein. Open Mind would win five consecutive Grade One races during her sophomore campaign, and won the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies.

“I had Open Mind as a 2-year-old in Saratoga,” said Bradshaw. “I had 50 head of horses up there, and she was one of them but because she was a Jersey-bred, I sent her to Kiaran McLaughlin, and the rest is history. When I went back to the farm, I got her back a few times a year, and another horse Is It True, the year that he won the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile (1988).”

A program that works

Lukas’ altruism still resonates deeply with Bradshaw, and his admiration and respect for the Hall of Fame conditioner is palpable.

“Wayne gave me Is It True’s ring because I had him all the time, Kiaran got Open Mind’s ring and Jeff (Lukas) got Gulch’s,” said Bradshaw. “Wayne was good about stuff like that. He was always very good to us. It was probably the best job a person could get.”

The Hall of Fame trainer’s understanding of the industry, sport, business and the logistics involved, allowed Lukas to achieve optimal results, said Bradshaw.

“He always had good horses, and Wayne just sent you some place and left you alone and let you train the horses,” said Bradshaw. “They have a program, and you stuck with the program, and it worked. Jeff (Lukas) kind of instituted the program, like with fillies, like Winning Colors. Everybody always talked about galloping horses a mile and-a-half, two miles all the time. Jeff wasn’t like that. Winning Colors never galloped more than a mile and an eighth or a mile in a quarter in her life. And our fillies were like that.

“Fillies that were light and didn’t eat well, maybe when they were fit, and for the colts the standard was a mile and a quarter gallop,” said Bradshaw. “Dynaformer, I don’t care who it was. Dynaformer may have galloped a mile and-a-half once because he was a tough sucker, but most colts galloped a mile and quarter and the fillies a mile and an eighth. That was pretty much the program, and it worked really well. What it did was leave something in the tank. It’s real easy to get these horses over the top before they get wore out and tired. And that’s where astute trainers do a very good job. You don’t train as far, you maybe change up the work schedule, spread it out a little bit.”

You got to have heart

If you have the talent on your roster it makes things far easier. A deep talent pool provides you with opportunities most conditioners don’t have the luxury in ever possessing. Equine athletes are very much like their human counterparts and possess certain attributes that make them elite, and those characteristics are not just limited to their physical abilities, said Bradshaw.

“One thing that I’ve found out about really great horses, is I think anyone can train one,” said Bradshaw. “They have that will to win and that desire. You can’t put that in them. They either have it or they don’t.”

An amiable demeanor, great understanding of the industry, and the ability to connect with people in multiple ways, has enabled Bradshaw to succeed at the highest level.

“As trainers go, I get along with all of them,” said Bradshaw. “One thing about this business, you don’t want to burn bridges. You just want to do the best job you can. If someone isn’t happy, wish them luck, and hope they come back some time. In this game, it’s pretty tough keeping people happy all the time. We have a pretty good record, in order to be able to keep the clients that we’ve had for as long as we have.”

The right horse

A case of mistaken identity was Classic in every sense. A colt was sent to Bradshaw ‘s operation, it happened to be the first one he would ever break and train for Mary Lou Whitney and John Hendrickson.

“John calls me and says, ‘How’s that gray Storm Cat doing?’ I said, ‘He’s not gray. He’s bay.’ I come to find out that they sent me the wrong horse. It was their horse, but they sent me the wrong one. They told me it was a Storm Cat, but it ended up being Birdstone.”

His talent was apparent from his nascent stages in training, demonstrating a precocity and ability that was redolent of something far greater.

“The funny story was, the girl that got on him every day, Melissa, she said, ‘You ought to get on this horse, he so athletic (she stated emphatically),’” said Bradshaw. “So, I got on him and galloped him one day, and he was. The same thing with Winning Colors, I galloped her at the farm as a baby too. Those kind of horses stand out early on. Winning Colors was a tough horse to be around in the stall and stuff. She was more like a colt, a big Amazon, strong filly. Open Mind and Lady’s Secret were little bitty fillies. It’s not how big they are, it’s how big of a heart they have. That’s what it comes down to. Quite a few of them have ability, but most of them don’t have that want to and kind of try. That only comes with the special ones. Even Nadal, I knew early on he was a good horse.”

Larger than life

Winning Colors was a horse that couldn’t get enough of training, she didn’t refuse to do anything, and she was what Bradshaw described as big and tough.

“She was like a monster,” said Bradshaw. “I ran her at Keeneland one day, it was in the Spinster… and she ended up like running fourth. She came back and drank like three buckets of water. She was exhausted. I don’t know if the racetrack that day was a little bit deep, cuppy or something, but she struggled with it. We took her back to Churchill and this was before the Breeders’ Cup, and I’m training her, and I trained her light. I trained her no longer than a mile every day. And then she just got beat by Personal Ensign (the 1988 Breeders’ Cup Distaff). That’s the thing about knowing horses and knowing what to do. If they’re a little bit over the top, like she was, when it was time to race, you don’t keep going to the well, you back up a little bit.”

A surprising victory

A chestnut colt by Storm Cat out of the Alydar mare Train Robbery, who was campaigned by William T. Young’s Overbrook Farm, gave Bradshaw one of the great thrills of his career. Cat Thief’s victory in the 1999 Breeders’ Cup Classic (Gr. 1) at odds of 20-1, still resonates powerfully with the horseman more than two decades after the 1 ¼ length win.

“The year that we won with Cat Thief is still one of my favorite moments with Wayne training horses,” said Bradshaw. “I sat with him on the pony forever. But when he got there, he lightened up on all his horses. He only galloped them a mile, freshened them up, all of them were bucking and playing, feeling good. Cat Thief when he was going for home in the Classic and Pat Day was just on him…I rode Pat so many times, and when he sits that long, you’re never going to beat him. He was so talented. When that horse turned for home, I was yelling and screaming because we were going to win the Breeders’ Cup Classic with a horse that was 20-1. Wayne did a great job training that horse.”

Team Lukas also had Padua Stable’s Cash Run, a dark filly by Seeking the Gold, out of Shared Interest by Pleasant Colony, who captured the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies (Gr. 1).

Indelible imprints

However, the 1994 Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies, a contest that featured two Team Lukas starlets, remains one of Bradshaw’s all-time favorite races.

“Flanders and Serena’s Song, for the last half mile they were never a head apart,” said Bradshaw. “It was one of the greatest 2-year-old races I’ve ever witnessed. They were both great fillies.”

Another of his fondest memories was that of a bay Florida-bred gelding by Prospector’s Gamble, who was named Grady, after a gentleman by the name of Grady Sanders.

He won a race that was run only once, but it was for an exceptional purse, $500,000. Grady would beat an impressive field including 1998 dual Classic winner Real Quiet. He was campaigned by Irish American Thoroughbreds and O’Leary’s Irish Farm.

“They had a race in Santa Fe, New Mexico for 2-year-olds called the Indian Nations Futurity,” said Bradshaw. “I sent him over to run in the trials, and he ended up running second in one of the trials. Real Quiet ended up winning one of the trials. There was another horse, General Gem that Eric Kruljac had. He won his trial. I took my horse back to California (prior to the race). I used to train in Denver, so I know what the altitude does to you. They left their horses there. My horse wasn’t the best horse, but he shipped back and ran super. He was still a maiden. He was a mean son-of-a-gun.”

Earlier in his career, Bradshaw like many in the Thoroughbred business would work long hours, get by on little sleep, but was so driven and motivated by their passion for the horse.

“While working for Lyman, I would get up, clean 10 or 12 stalls, and then get on 10 or 12 and then I would pony horses to the post all afternoon,” said Bradshaw. “I loved it. That’s what I wanted to do. You’ve probably heard Wayne say, ‘I ask my guys to work half a day, and what they do with the other 12 hours is up to them.”

A career steeped in memories, with horses and people who made the game great, legends of the turf, whose presence and participation were larger than life, were accessible to Bradshaw early in his career.

“When I first went to southern California, I used to go to the trainers lounge at Hollywood Park,” said Bradshaw. “Charlie (Whittingham) would be in there, Laz Barrera, Gary Jones and all those trainers that I read about when I was a kid growing up. I went in and got to have lunch with all those guys.”

His sons (twins Brett and Lance) aren’t involved in the business, but have owned pieces of horses with their father, and currently have an Into Mischief colt with their dad, who eventually will go to George Weaver.

His daughter Ashley, the youngest of Bradshaw’s four children and whose mother is his ex-wife Alicia, works for Kerry Cauthen at Four Star Sales. But it was an encounter between his daughter and the legendary ‘Bald Eagle’ that Bradshaw cherishes, having left an indelible imprint that resonates deeply.

“One of my favorite all-time memories was when we were coming out of the stable gate at Santa Anita one day going toward the receiving barn,” said Bradshaw. “Charlie was walking back up the road, and Ashley my daughter, who’s now 29, and she was very small, I said, ‘Hey Ashley, there’s Charlie.’ So, she runs up to Charlie and she wraps both her arms around his leg. He bent over and put his hand on her head and was talking to her. Charlie was awesome.”