By John Scheinman

In the three decades following the Civil War, rich men with outsized ambitions began to shape the future of America. Captains of industry or robber barons, depending on your perspective, they built a country on industrialization, steel, railroading and untethered capitalism.

With all the miserable North-South bloodshed out of the way, the wealthiest Americans got down to the business of doing what they really wanted – to make money and have a good time.

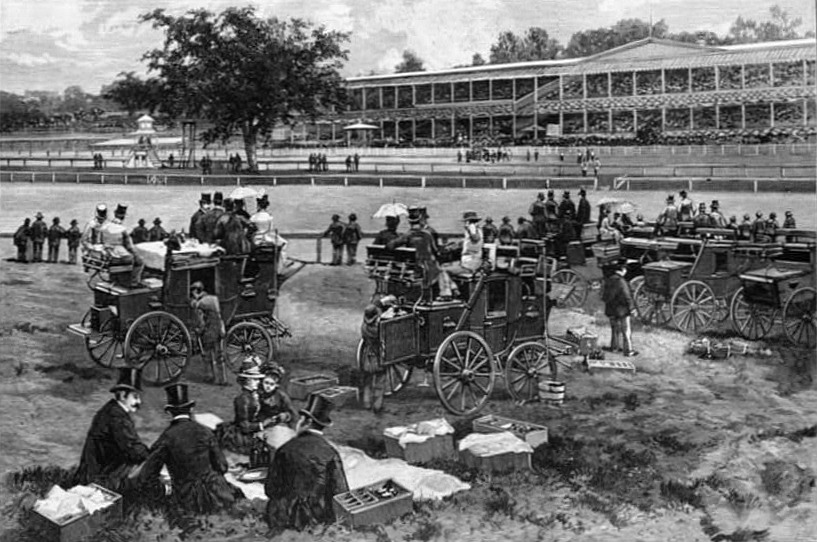

“The Gilded Age,” as Mark Twain later termed it, also ushered in a golden age of horse racing, as massing fortunes were applied to the purchase of sprawling estate properties and wide-open land tracts to build racetracks that doubled as pleasure palaces, where impossibly rich men and women from the highest levels of society could compete, show off their bling, see and be seen. The Gilded Age turned luxurious high living into a decadent art.

Into this world strode two brothers, George and Pierre Lorillard IV, heirs to the Lorillard Tobacco Company founded by their great-grandfather in 1760. With fortunes conveniently secured well before their birth, an intense passion for horses and sporting competition drove the Lorillards to the top of the racing game. When the sport in Maryland, devastated by the war, revived with the building of a new track called Pimlico in Northwest Baltimore, the Lorillards helped make its fame, sensationally dominating the early running of its most prestigious race, the Preakness Stakes.

Pierre Lorillard IV won the fourth Preakness with his horse Shirley in 1876. Two years later, George, who followed his brother into racing, began a record run unbroken to this day, winning the Preakness five straight times, with Duke of Magenta, Harold, Grenada, Saunterer, and, lastly, Vanguard in 1882. All five were trained by Hall of Famer R. Wyndham Walden.

The Lorillard brothers, already renowned for prior exploits in yachting, became ranked among the most famous and well-regarded sportsmen in the country.

In “Who’s Who in Horsedom Volume VIII,” published in 1956, author J.H. Ransom set the tenor of the Lorillard’s times: “The three decades prior to the turn of this century made up that nostalgic period during which time Grant was president, a lackadaisical government had problems of its own, the Union Pacific Railroad Company scandal rocked the world of finance, taxes were virtually nonexistent by today’s standards, and business tycoons vied with industrial magnates to dominate the prodigious era of rising financial empires. Baronial estates epitomize this plush age, and the landed gentry found its greatest enjoyment and relaxation in the ‘sport of kings.’”

Lorillard’s Tobacco Legacy

Pierre Abraham Lorillard, the founder of the oldest tobacco company in the United States, was born in France in 1742 and at around age 18 immigrated to New York and became the first person to make snuff in North America. Before being killed by German mercenaries fighting for the British during the Revolutionary War, Lorillard also made pipe tobacco, cigars and chewing tobacco in New York City.

It was a good business to be in because at the time nearly everyone enjoyed tobacco. In his book “The Shipcarver’s Art,” which tells the story of the once ubiquitous presence of Indian representations at cigar stores, historian Ralph Sessions wrote about tobacco use rising in the late 1600s. It “was not a male prerogative. On both sides of the Atlantic, it was popular among women and children of all social classes, and little evidence survives to suggest any widespread gender or age prohibition until the 19th century. The Lorillard company’s big seller was Tiger brand chewing tobacco, “marketed in colored tins with a faux wicker print and its iconic tiger logo,” according to the Green Wood Historic Fund.

Lorillard grew to be one of the biggest tobacco companies in the world. Later cigarette brands it was known for included Kent and Newport. The Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society in Alabama believes Pierre Abraham Lorillard was likely New York’s first millionaire. By the time his great-grandsons took over the company, the family possessed more than 600,000 acres of land in New York.

One of them, Pierre Lorillard IV, didn’t make any bones about which direction his life would head. He was going to run the tobacco business and also develop luxury real estate properties and sporting preserves, race and breed horses. Brother George tried to go on the straight and narrow. He went to Yale and graduated in 1862 with a science degree. He was qualified to practice medicine but never did. The New York Times reported that he studied medicine for another year and then gave it up and joined his brother in the family tobacco business.

Before discovering horse racing, the Lorillard brothers already were accomplished yachtsman as members of the New York Yacht Club. Ships long had been used for transporting cargo, people and fighting wars, but the New York Yacht Club had been gifted the America’s Cup in 1857, and sailing men began building boats for speed to compete. Pierre Lorillard IV famously raced his yacht the Vesta in the calamitous first midwinter transatlantic race, billed as “The Great Ocean Yacht Race,” against James Gordon Bennett Jr., the carousing heir to the New York Herald, and financier George Osgood.

In an article in The Guardian on the book “Gordon Bennett and the First Yacht Race Across the Atlantic,” Charlie English wrote, “The dawn of ocean yacht racing can be pinpointed to a drunken night at the exclusive Union Club, on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, in October 1866. That evening, a group of super-rich playboys of the burgeoning New York yachting scene – Pierre Lorillard, George Osgood and James Gordon Bennett Jr. – gathered to drink and brag about the performance of their respective schooners. Insults and challenges were swapped, and by the time the men staggered out into the dawn in an alcohol fug they had signed up to a dangerous race across the full width of the north Atlantic in midwinter. Each owner would stump up a $30,000 stake, and the winner would take all.”

Six men lost their lives in this race, swept from the Fleetwing of Osgood into the sea as enormous waves crashed over the ships, but all finished with Bennett’s Henrietta reaching the Isle of Wight first in just under 14 days.

George Lorillard, who also liked pigeon hunting, lost a ship he had built when it went down off the coast of the Bahamas. He contracted for another called the Meteor, which wrecked in the Mediterranean in December 1869, 75 miles east of Tunisia, where it was captured. Fifteen years later, the New York Times wrote that Lorillard had to pay $15,000 in ransom to get the ship “out of the hands of Arabs.” He built one more boat but gave them up for good in 1872. As with tobacco, he decided to follow his brother into horses.

The Inspiration

Once Pierre Lorillard IV got a whiff of the high life at the Jerome Park racetrack, it’s not hard to understand why he thought, ‘This is the life for me.’ How could a young playboy sportsman not be cast under the spell of Leonard Jerome, Winston Churchill’s maternal grandfather?

According to the Winston Churchill Society, “Jerome’s life started humbly in 1817: he was one of ten children who tended chickens and other livestock on father Isaac’s farm in Palmyra, New York.”

After graduating college, Jerome studied and practiced law and then founded a successful newspaper. In 1849, he accelerated his ascent, marrying a rich heiress and moving to New York City.

“People like Belmont and Jerome do not enter society, they create it as they go along,” – often-used uncredited quote from a contemporary of Leonard Jerome and August Belmont Sr.

Jerome was the rare kind of man with an instinct for the future. He and his brother Lawrence invested in a telegraph company that laid cable across the Atlantic Ocean. In fact, when Lorillard, Osgood and Bennett put together their transatlantic yacht race, Jerome intuited an opportunity to show off the telegraph’s prowess and make headlines. He goaded the men along to go through with their drunken folly, and of course he was right.

By the time he hit his 40s, Jerome was known as the King of Wall Street. History records that he made fortunes, lost them, and then made them again. He and his brother opened a stock brokerage and generated interest in it by cultivating relationships with newspaper editors and planting stock tips, according to the Churchill Society. Soon, he was worth $10 million at a time when there were virtually no millionaires at all.

Jerome’s predilection for extravagance presaged the Gilded Age. From the Churchill Society: “A competition started in the mid-1850s to build lavish mansions. [Jerome] set the pace.”

He built “an opulent palace. Ballroom fountains could flow with champagne, and it had a 600-seat opera theater, a 100-guest dining room, a breakfast room for seventy, and a carriage house with elegant paneling and stained glass windows. Their horses lived better than most New Yorkers.”

In New York City, Jerome was a celebrity. He also was well known as a womanizer and a gambler. He bought into ownership of the New York Times, and when the Civil War draft riots broke out in lower Manhattan in July 1863, Jerome had Gatling guns mounted in the windows of the newspaper building. The mob objecting to fighting the war certainly wanted none of that.

After the war, Jerome went hunting out west with Buffalo Bill Cody, and in 1866 bought an estate in Westchester County, New York, and, together with August Belmont Sr., built a magnificent edifice in honor of himself, a racetrack they named Jerome Park.

In his 1916 book, “Cherry and Black: The Career of Mr. Pierre Lorillard,” turf historian Walter Vosburgh described the revival of horse racing at the close of the Civil War, writing “Jerome Park became at once the headquarters of sport and the Mecca of fashion.”

One newspaper of the era reported that the track “illustrated the triumph of civilization.”

The race horses at Jerome Park were the cream of the crop, as were the people. Vosburgh wrote that men and women arrived “as on an evening at the opera among the boxes.”

The track’s clubhouse, which included overnight accommodations so patrons could step out in the morning to witness the gallops, was nothing short of palatial. “Its saloons, its cheerful halls, its spacious ballroom where melody so often echoed and which, as the door of the south wing opened, burst upon the view with its great quaint old Louis XIV fireplace and arm-chairs, casting a grey light of antiquity upon the scene – all these contributed to the senses of comfort and pleasure.”

Famous races run to this day were born there: the Belmont Stakes, the Champagne, The Ladies.

“There was a ‘racing spirit’ at Jerome Park,” Vosburgh wrote, “a smell of real sport.”

“It was the influence of such surroundings as these that attracted the interested Mr. Pierre Lorillard in racing, and finally brought him within the fold of American turfmen among whom for the following thirty years he was one of the most conspicuous.”

The Birth of Baltimore Thoroughbred Horse Racing

Pimlico Race Course, after Saratoga, is the second-longest operating racetrack in the United States. It opened in 1870 and conducted its first spring meet three years later, debuting the Preakness Stakes, now the middle leg of Thoroughbred racing’s Triple Crown and one of the most famous races in the world.

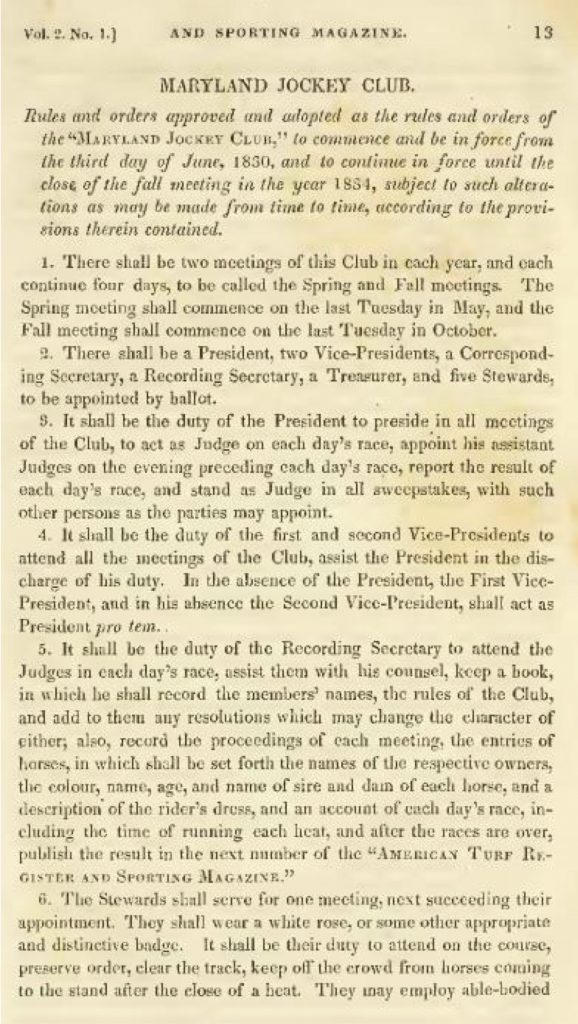

The first rules and regulations for an American race track were published by the Maryland Jockey Club for use at its Baltimore City home track Central Racecourse, which opened in October, 1831. The MJC is America’s oldest sporting organization, having begun in 1743 with racing in Annapolis, Maryland. George Washington’s diaries record that the races in his day were more social occasions than organized sport. The rule book was approved in June, 1830 and published in September. By 1830 horse racing was highly organized.

Yet, racing had been prominent in Baltimore before. The first home track of the Maryland Jockey Club – founded in 1743 and the oldest sporting organization in the country – was Central Racecourse, on the west side of the city. It successfully operated from 1831 to 1861 and then came to ruin when its horses were siphoned into the Civil War.

The sport lay dormant in Maryland for seven years, until an enterprising politician named Oden Bowie took it upon himself to conjure its revival. Bowie perfectly fit the times. He had been the youngest captain in the U.S. Army, a promoter of railroading and then a politician who rose up to be Maryland’s governor. Though his life was in the State House and Governor’s Mansion, his heart was with the horses.

In the summer of 1868, the most famous dinner party in Maryland racing history took place out of state, at the Union Hotel in Saratoga, New York at the end of the racing season. The extravagant evening’s host, Milton Sanford, was as nuts about racing as any of them. The owner of wood and cotton mills, he had made his fortune selling blankets to the Union Army during the Civil War.

John Hunter, fresh out of Congress, proposed the revelers commemorate the evening by creating a race called The Dinner Party Stakes. The sportsmen in attendance decided on a race for yearlings featuring horses owned only by those in attendance. The purse would be enormous – $15,000 – but the winner would be required to host the losers for dinner. Seeing his opportunity, Bowie, the newly elected Maryland governor, jumped in and said not only would his state host the race, but a new track would be built for it.

With that, the moribund Maryland Jockey Club awakened from its sick bed and purchased 70 acres of land, and the new track was built for $25,000 with financial help from the dinner party guests.

On Oct. 25, 1870, Pimlico opened for racing. A crowd of 12,000 showed up to see the new grandstand, with its three spires and a clubhouse designed in the Victorian style. The next day the winner of the Dinner Party Stakes was Sanford’s colt Preakness. Three years later, the track hosted its first spring meet with a new stakes for 3-year-olds named after the winner of the first Dinner Party Stakes.

As the late Maryland racing historian Joe Kelly wrote, “Pimlico was Maryland’s answer to the fashionable tracks at Saratoga, Metairie near New Orleans and in Kentucky.”

As all of this unfolded, Pierre Lorillard IV was building his Thoroughbred empire. In 1872, he developed his Rancocas Stud Farm on 1,500 acres in Jobstown, New Jersey. The stallions he shrewdly bred to rank as the finest of the second half of the 19th century and among the best ever. One, Lexington, was the sire of the horse Preakness, as well as Preakness Stakes winners Tom Ochiltree, Shirley and Duke of Magenta. The other, Leamington, sired Aristides – the first Kentucky Derby winner – and Lorillard racing immortals Iroquois and Parole. Leamington also sired Harold and Saunterer, both Lorillard winners of the Preakness Stakes.

Pierre Lorillard won the fourth Preakness Stakes with Shirley in 1876, but it was the race advertised as “The Great Sweepstakes at Pimlico” – the Special – that raised the Lorillard name, and the racetrack’s, to new heights. This was when Lorillard matched his Parole against the invincible Ten Broeck, who had won 14 of his past 15 challenges, and Tom Ochiltree, winner of the 1875 Preakness.

Anticipation of the showdown grew to obsession. Vosburgh wrote that Ten Broeck “had been proclaimed the horse of the century” during 1876 and 1877. Owners simply stopped pitting their horses against him, so he was left to compete against times achieved by previous horses. Ten Broeck, Vosburgh wrote, had been setting records in the West but finally was lured to Baltimore for the 2 ½-mile confrontation with Parole and Tom Ochiltree on Oct. 24, 1877

Kelly wrote that the crowd was estimated at 20,000. Congress shut down in Washington and chartered a special train to deliver the legislators to Baltimore. Vosburgh wrote that Lorillard’s Parole “looked as rough as a bear and lean as a snake,” compared to the “magnificent specimen” that was Ten Broeck.

Each owner had put up $500 and the Maryland Jockey Club added $1,000 to the purse.

“The Kentuckians bet heavily on Ten Broeck,” Kelly wrote. “Virtually everyone overlooked Parole, but Lorillard and his retinue of admirers accepted all offers. Parole won by four [Vosburgh says five] lengths. Lorillard collected a fabulous sum, hundreds supposedly went bankrupt, and the Maryland Jockey Club profited handsomely.”

Pierre Lorillard went on to become one of the first sportsmen to take American racehorses to England to compete. He went loaded with Parole, who won the Newmarket Handicap in 1879 against one of the best English horses of the time, Isonomy. The victory created a sensation in English racing, according to Vosburgh. Six days later, Parole won the City and Suburban, one of the most important English Handicaps. A day later, with all competition scared off, Parole competed in the 2 ¼-mile Great Metropolitan, beating a lone sacrificial opponent. Iroquois, meantime, captured English races that still rank among the most important to this day: the Epsom Derby, the St. Leger, the Prince of Wales Stakes, and St. James’s Palace Stakes.

These exploits reported from overseas had a profound effect on American racing.

As Ransom pointed out, Parole’s exploits made the horse one of the leading American sporting figures. “Racing clubs were formed, and social clubs were named for the horse. There were Parole poolrooms, Parole saloons, Parole baseball clubs, all adding to the inescapable fad of the time.”

Vosburgh wrote: “It was the success of Iroquois and Parole that gave the great impulse to racing in America, in that it attracted the attention and aroused the pride and the interest of the people in the sport and led to its wonderful growth and popularity throughout the country.”

Pierre Lorillard IV spent more money on race horses, yearlings, broodmares and stallions than any other man of his generation. He outlined the first plans for governing the sport in 1890, leading to the Board of Control, which eventually merged with The Jockey Club. He was the first to experiment with and ultimately outfit his race horses with aluminum plates (made to his specification by Tiffany & Co.), much lighter metal than ever used before on the feet of horses.

Yet, through all the success of Pierre Lorillard, the brief run by his brother George was perhaps more extraordinary. It began in 1874, when he entered into a stable partnership with James Lawrence, president of the Coney Island Jockey Club, which had built Sheepshead Bay Race Track in 1879. Pierre helped finance the construction.

Success came immediately as George Lorillard and Lawrence won the Champagne Stakes with Hyder Ali, a colt named for the Sultan of Mysore in Southern India.

George Lorillard went out on his own the following year, in 1880. He established his Westbrook Stables on 1,000 acres in Islip, Long Island, and hired Hall of Fame trainer R. Wyndham Walden, of Carroll County, Maryland, one of the most dominant horsemen of the latter part of the 19th century.

Walden had trained Tom Ochiltree to win the Preakness in 1875. George Lorillard bought the horse from owner John Chamberlin and engaged Walden in 1878. Their partnership was electric. Duke of Magenta, by Lexington, won the Preakness and also the Withers, Belmont Stakes and Travers that year. The victory in the prestigious Belmont Stakes, defeating Pierre Lorillard’s favored Spartan, only enhanced the reputation of the Preakness Stakes. Pierre subsequently bought Duke of Magenta from his brother for $15,000.

In a stunning display, George Lorillard horses swept the Preakness five times, from 1878 to 1882, and Kelly wrote that the era at Pimlico became to be known as the “Lorillard years.”

“Those five years of quality fields in the Preakness enabled the race to be acclaimed as an American classic and to be compared with England’s Epsom Derby,” Kelly wrote.

George Lorillard’s Brief Life and Long Legacy

George Lorillard’s success and life were brief. His stable had grown to be the second largest in the country, next to his brother’s. Yet in 1882, Walden left him to strike out on his own.

Only 40 years old, his health began deteriorating from what the New York Times reported as a “hip disease.”

On March 10, 1884, the Times reported Lorillard would retire from the turf and sell Westbrook – the stables, training track and horses. He traveled to St. Augustine, Florida, hoping the warm weather would improve his health. He sold everything, except his two favorite runners, Sensation and the filly Spinaway.

Eventually, he moved from Long Island to Monmouth County, New Jersey, and then, lastly, to Nice, France, hoping again the climate would heal him. His death at 43 on Feb. 3, 1886, was described as being from “rheumatic gout.”

The racing publication The Spirit of the Times wrote on Feb. 6, “No event of the kind that has happened in years could have been the cause of more general regret, nor can we record the death of a turfman or sportsman who has ever enjoyed an equal degree of popularity.”

After his funeral April 18 at Grace Church in New York, the Times reported, “It has been requested that no flowers be sent, but the casket was almost filled in a bank of white roses and immortelles. In the rear seats were old servants and Tom Costello, the jockey who had ridden Lorillard’s final two Preakness winners, Saunterer and Vanguard, and other young jockeys who had faithfully carried the orange and purple for many years.”

A month after his brother’s death, Pierre, the joy gone out of him, announced he would retire from racing.

“The keen rivalry between George and Pierre was well known among horsemen,” Ransom wrote. “There was no victory as sweet as that which one brother could win over the other. This competition was of such great and sincere mutual enjoyment because there was not the slightest vestige of malice or jealousy.”

Pierre Lorillard didn’t fully leave racing until 1896, when he held two dispersal sales of his horses, one in February and the second in October. Ransom wrote that a special train was added to the railroad line to accommodate “trainers, breeders, jockeys, bookmakers, officials, race goers and sporting journalists . . .”

When Pierre Lorillard died at 67 in July 1901, his estate was appraised in December of that year, and “the amount of it came as a great surprise to many, who had imagined Mr. Lorillard a great deal wealthier man,” the Thoroughbred Record reported. “The personal estate is valued at $1,797,925.23, instead of some five or six million as generally anticipated.”

In death as in life, the Lorillards left little on the table.

Mike Veitch, historian at the National Racing Hall of Fame, who comes from a long line of horsemen, put the Lorillards in historical context.

“Their record in the Preakness is kind of reflective of the impact that the Lorillards had on the game,” Veitch said. “If you think about it in historical terms, we’re speaking of the brothers and the Gilded Age, the late 19th century, from our perspective they’re two sportsmen who really enjoyed all the pursuits of the day. It was pretty impressive. They lived life to the fullest, it seems. If you go to the racing aspect, to me they are of their era the great patrons of racing.”

John Scheinman is an Eclipse Award-winning writer who has published stories in The Baltimore Sun and BloodHorse.

Photo of Duke of Magenta courtesy of the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame