If not for the Coronavirus, this would be Preakness week and the last of the Preakness contenders would be arriving at the facility today. The Kentucky Derby winner would take up residence in stall 40 at Barn E in the Preakness stakes barn. Unless you’re Bob Baffert who prefers a quieter location away from the buzz and media. Or Neil Drysdale with Fusiachi Pegasus in 2000 who came early to scope out a better spot.

When the next Preakness takes place at Pimlico, the Maryland Jockey Club (MJC) will be tenants and no longer owners of the facility. With passage of a new Maryland law last week, ownership of the historic racetrack will pass from the MJC to Baltimore City and MJC will lease Pimlico for the duration of the Preakness meet.

If the Preakness is held in October as rumored, the date will be close to Pimlico’s historical anniversary of October 23, the first day in 1870 the public was invited to Pimlico.

Old Hilltop has seen many changes in its 150 years. And it has been tested by time. It has lasted through wars, fires, strikes, the waning of the Sport of Kings and the early 19th century pandemic.

Over the years there have been many owners with different visions. And a mix of architecture from the original Victorian to state-of-the-art for its time Mid-century Modern. Pimlico is an eclectic homage to every period in American Thoroughbred horse racing. Although the only remaining part of the original Victorian era, the wrought iron gates, are now at the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in New York.

Since the 1990s, there has been much talk of moving the Preakness from Pimlico. This is actually not something new. Surprisingly, the man who uttered the phrase “Pimlico is more than a dirt track bounded by four streets. It is an accepted American institution, devoted to the best interests of a great sport, graced by time, respected for its honorable past,” was willing to walk away from Pimlico and take the Preakness with him. Alfred G. Vanderbilt, Jr., was quite ready to build a new facility at another location. Laws were even tweaked to make it a possibility in the 1940s. But as we all know that didn’t happen. So much did happen at Pimlico.

Fire, fury, and Triple Crown flurry

From 1894 through the mid 20th Century Pimlico Race Course experienced many changes. Some are well documented, others still obscured while some known information is conflicted. Throughout, the one thing that remained constant was the old Members Clubhouse, the oldest structure in American horse racing.

There are very few images of Pimlico during this time period. Many are from postcards of the popular facility that date from 1915 to 1951. They do illustrate a new grandstand next to the two-level observation stand beside to the paddock. An additional structure known as the “Little Clubhouse” was on the other side of the paddock and can be seen in the background of many photos of historic races.

On September 2, 1894, fire destroyed Pimlico’s Victorian-style grandstand. In 1889, the Maryland Jockey Club abandoned racing at Pimlico. During this period, several Maryland racing groups held abbreviated meetings at Pimlico, some called “outlaw” affairs, some sanctioned.

With Pimlico not officially open, the Preakness was run at Morris Park in New York in 1890. For that year only, it was for horses three years old and up. The Preakness was not run 1891 through 1893. Subsequently, the race was moved in 1894 to Gravesend in Brooklyn, New York where it remained through 1908.

Maryland Jockey Club Sells Pimlico

In 1905, the 78 acres of the Pimlico property were sold to William R. Hammond for $70,000. Pimlico was opened again for Thoroughbred racing with the help of William P. Riggs but without the Preakness. A young James E. (Sunny Jim) Fitzsimmons was the leading trainer at the seven-day fall meeting with three winners.

The new owner, Mr. Hammond, was a former senior partner of Hammond, Snyder & Co., a grain exporter, was president of the Third National Bank of Baltimore. He had also been a member of the Baltimore Chamber of Commerce for 20 years.

In 1909, the same year the Preakness would return to Pimlico, Mr. Hammond died in December of a sudden heart attack at the age of 46. Fittingly, he died at Pimlico’s clubhouse. The ownership of Pimlico would pass to Hammond’s heir, his daughter, Mrs. Audrey Hammond Madden, and held in a trust held by Safe Deposit and Trust Company of Baltimore (now Mercantile).

Maryland Jockey Club Requests To Buy Back Pimlico

Since 1905, the Maryland Jockey Club had been leasing the track for meets. In 1938, when Alfred G. Vanderbilt, Jr., became MJC president and a major stockholder in MJC, the Club offered to buy Pimlico for $800,000. That offer was rejected and the Club continued to lease.

In 1946, a question which had become of significant importance was the adequacy of the physical facilities at Pimlico, and the feasibility of improving them, or of moving to a different location. The current MJC lease was to expired in 1949. The Jockey Club suggested that it would purchase the property for a price of $700,000. Mercantile informed Mrs. Madden of the new offer which she declined.

Later in 1946 Mercantile had the land appraised which was valued at $540,000. A Philadelphia engineering firm, suggested by Mrs. Madden’s attorney, made a study primarily to determine what it would cost the Jockey Club to relocate its racing operation, and to duplicate Pimlico’s physical facilities at a new location.

One of the conclusions of that study was that the improvements at Pimlico could be reproduced new at a cost of approximately $1,600,000, and that their current depreciated value was $1,000,000. Mercantile noted that the value of the Pimlico property, at least by one approach, was indicated to be $1,540,000.

Mercantile also approached the question of value in other ways. It made studies by capitalizing rents, adjusted for what it considered to be valid factors, using several different assumed rates of return. Possible values ranged up to a figure in excess of $2,000,000. Mercantile concluded that $1,500,000 was a reasonable value. It put that figure to the Jockey Club as an asking price that would be negotiated.

Other factors considered affecting the value were that the Jockey Club, not the trust, owned the names of several well known stakes races run at Pimlico, most famous of which was the Preakness. The Jockey Club, not the trust, was the licensee for conducting horse racing at Pimlico.

For additional value it was determined that Pimlico had an excellent location and was steeped in tradition. The imponderable question was how much of that tradition attached to the site or the name of the site and how much attached to the Maryland Jockey Club and the Preakness. At the time Pimlico’s improvements were very old and, although well-maintained, they were obsolescent and well below standard for a modern racetrack operation in the post-World War II era.

A Battle Over Value And Law

At that time, State laws in effect froze major racing at mile tracks in Maryland at the existing four locations. The General Assembly session of 1947 saw indications of change. A bill was introduced which would authorize any of the four major licensees to conduct racing at a different location, but which would still limit the number of licensees to four.

The parties met as adversaries in the lobbies and halls of the State House. Intensive lobbying activities were conducted on behalf of each. As the session was nearing its end, the lobbyists for Mercantile were successful in bringing about an amendment [the Miles Amendment] to the bill which would permit a licensee to relocate, but would then permit racing at five locations. The amendment was passed by the Senate on second reading by a vote of 15 to 13. It was clear that if that amendment became a part of the law, the owner of Pimlico Race Track would have to deal with a tenant which had alternatives.

The Jockey Club could stay, under a new lease, or it could relocate. If it relocated, the trust would be required to seek another operator, one which could obtain a license, and which could then conduct horse racing at Pimlico. Pimlico would then be one of five, rather than four, major tracks in Maryland. If the amendment failed of final passage, the owner of Pimlico would have little more than a piece of real estate, appraised at slightly over one half of a million dollars. Before the Senate Bill came up for third reading, a memorandum of agreement was reached by negotiators for the Jockey Club and Mercantile. The Jockey Club would buy the property for $1,115,000.

When Pimlico Was America’s Premier Track

During the time Pimlico was held in trust, the facility would see a golden age of racing. In 1919, Sir Barton would become the first Triple Crown winner having won the Preakness four days after his Derby victory. Man ‘o War, skipping the Derby, began his 3-year-old campaign in the Preakness. The Dixie was revived, the Pimlico Futurity and Pimlico Special inaugurated, and, in 1938, the most famous match race in history between Seabiscuit and War Admiral. By 1948, Pimlico would also see seven Triple Crown winners grace its track.

Almost Gone Again

In 1958, a bill for closing Pimlico and transferring the dates to Laurel was defeated by a 15-14 vote in the Maryland legislature.

A Renaissance

The following year, the Cohens who owned the facility, built the new clubhouse from the ground up in the Mid-Century Modern style of the day with air conditioning. They also enclosed the large grandstand with glass with windows that opened for ventilation. There was no other facility like it in racing in the world.

To pay tribute to Pimlico’s historical past, the Cohens had a 4-ton bas relief sculpture erected on the side of the clubhouse wall. Three horses competing in the match race of the 19th century covered in 24 karat gold leaf. The 30 x 10 foot art depicted three Hall of Famers — Parole, Tom Ochiltree and Ten Broeck — in the Great Baltimore Sweepstakes of 1877. A race so important both houses of congress adjourned to attend.

The following decades would see a golden age for horse racing and Pimlico would thrive. There would be three more Triple Crown winners and many accomplished horses, jockeys and trainers at Pimlico. The Preakness would become not only an annual must for the local crowd but a yearly gathering for the must-haves as celebrities of all facets attended. In mid-May, Baltimore was the place to be. The infield became a right-of-passage. That would change a bit in the new century.

The New Era

Pimlico survived and will now see a new era. However, there will be no bustling backstretch, no morning workouts. No longer will trainers swap stories and grooms speak of generations of families on the grounds. It will be a shiny, sterile Pimlico made of glass without the smells of horses, hay and wood. There will be no apron where the railbirds can congregate. Yes, Pimlico has survived but somehow only in name.

Contrary to fable, Pimlico the racetrack was named for a township in London called Pimlico where Winston Churchill once lived. He said “The outside of a horse is good for the inside of a man.” You were so right, Mr. Churchill, you were so right.

Hi Ho Pimlico!

MbKalinich

Photos:

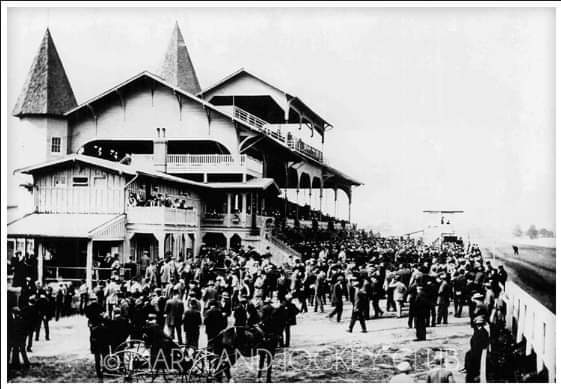

Pimlico as it was in the 1870s. Photographer unknown.

Pimlico’s paddock ca. 1900. Courtesy the Maryland Jockey Club

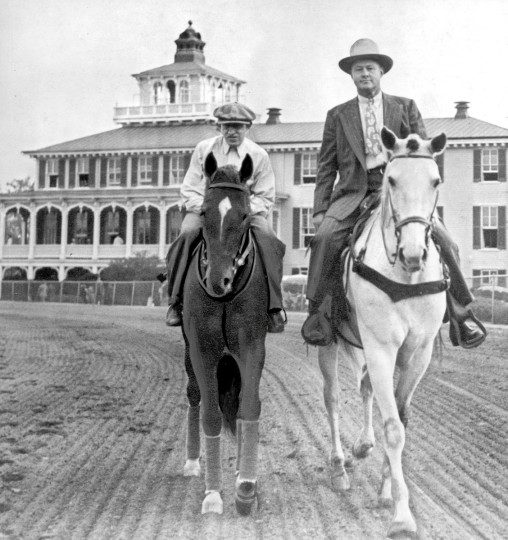

Whirlaway preparing for the 1941 Preakness at Pimlico. Exercise rider “Pinkie” Brown up with trainer Ben Jones ponying. Credit: Baltimore Sun file photo

Kauai King #3 overtakes Stupendous #8 coming down the stretch to win the 1966 Preakness. Credit: Baltimore Sun