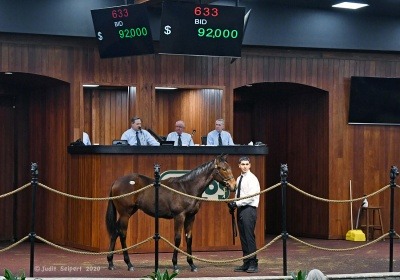

Photo Credit: Judit Seipert

This week’s sale of two-year-olds in training at Ocala Breeders Sales Co. was never going to set any records. As Nicole Russo carefully wrote in the Daily Racing Form, “the market was expected to show restraint.” But I suspect that few anticipated the extent of the debacle that occurred. In brief: the average price for horses that were sold dropped 34% from last year, from $144,603 to $95,585. The median price, typically a more representative reflection of the sale as a whole, dropped 37.5%, from $80,000 to $50,000. Of the 485 horses that went through the auction ring, only 291 were sold – a buyback rate of 40%, compared to just 24% last year. And those 291 sales represented less than 43% of the total number of 681 horses that were in the sales catalogue to begin with, the first time in my memory that fewer than half the horses listed found new homes. While some horses in the catalogue, as always, were scratched for physical reasons, or because they just breezed too slowly, it appears a good number were withdrawn because their owners correctly anticipated a poor market.

There are three overlapping reasons for the declines. First, the sale took place against the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic, which both limited the number of buyers who felt comfortable going to Ocala – though OBS did provide expanded telephone bidding – and created a huge amount of uncertainty. Will there even be places to race the two-year-olds that one is buying?

Second, the stock market is in free fall, down some 30% from its high point. And the sort of people who buy expensive racehorses are also the sort of people who have a lot of wealth in the market. So seeing their portfolios drop dramatically might, to say the least, inhibit their willingness to throw money at unproven thoroughbreds.

Third, even without the possibly temporary hiccup of the coronavirus and stock market crash, racing itself doesn’t have a rosy outlook. Betting handle has been flat – actually declining in inflation-adjusted dollars – for many years, and the recent explosion in sports-book betting on other contests threatens even that modest current handle. In addition, clusters of breakdowns – at Aqueduct in 2011, at Santa Anita last year – have strengthened public support for abolishing racing altogether. The recent indictments of “super-trainers” Jason Servis and Jorge Navarro and other racing insiders just adds to the public perception that racing is crooked, not to mention cruel.

Still, with the cancellation of the Fasig-Tipton Gulfstream sale and the Keeneland April sale, OBS March was the only place a buyer could look for a high-quality two-year-old that might be ready to race early in the year (assuming that there will be anywhere to race). So it’s a bit surprising that the top prices at the sale were only in the $600,000 range, plus or minus.

In most years, there are at least a few million-dollar babies. Last year, for example, the sale topper in March went for $2 million, and none of the five most expensive horses at that sale sold for less than $800,000. There can’t be that much difference in quality from one year to another, so the decline in buyers’ willingness to pay foolishly high prices for horses that probably won’t earn that money back on the race track – remember The Green Monkey! – must in large part result from the three uncertainty factors listed above – the virus, the stock market, and racing’s own uncertain future.

The OBS March results have unsettling implications for the rest of the thoroughbred sales season. Pinhookers, who buy weanlings and yearlings and then try to sell them at a profit as two-year-olds, need the money from those sales to finance another round of yearling buying. With the Gulfstream and Keeneland sales cancelled – though Fasig-Tipton did add another sale in June at Timonium, MD – it’s getting harder to see where pinhooking consignors will hit those home runs that fuel their next round of buying. Combine that with what’s likely to be a continuing stock-market miasma, and breeders who are sending their yearlings to the summer and fall sales must already be having palpitations.

The breeding industry went through one much-needed round of contraction after the financial crash of 2008, with the result that the US thoroughbred foal crop is currently down roughly 50% from its peak. By the time this year’s trifecta of virus, stock market and scandal have played out, thoroughbred racing and breeding may become even more of a niche industry than it already is.