Michael Bray has been able to adapt to the ever changing world of Thoroughbred racing.

There seemed to be no doubt as to what career route horseman Michael Bray would follow.

The son of a Thoroughbred trainer, Huey Bray, the assistant to Billy Carroll, who conditioned Charlie Boy, who won an astounding 58 races, had his own horse to ride by the time he was 6-years-old, a retired broodmare.

“I used to ride her all over,” said Bray. “I’d pull up to the side of the fence and jump on her back. That’s when I was at Isaac Prickett’s farm in South Carolina.”

Formative Years

Bray accompanied his father to the barn as a young child, while being exposed to the Thoroughbred industry, laying the foundation that would play a role for the rest of his life.

“They were breaking babies and they let me drive the tractor around,” said Bray.

The aspiring horseman would soon learn a valuable life lesson. The best advice he got from his father was not to fall off.

“One day, my father had this one really wild yearling that they were breaking, and everyone else was afraid to get on him,” said Bray. “He said, ‘You jump on the horse’s back.’ I said, ‘I don’t want to do it.’ He said, ‘You get on this horse’s back, or you’re not driving the tractor anymore.’ I jumped on the horse’s back, rode the hair out of him, and that was the beginning of it.”

Summer Fun

Bray would either attend school in South Carolina or New Orleans, as his father would often winter in South Carolina with his racing stock, because at that time there wasn’t any racing in New York or anywhere else northward From Thanksgiving Day until April 15 of the following year.

“He would refresh all of his stock and, give his older horses some time off and I used to break all the babies,” said Bray. “I remember when I was in South Carolina, my father would come after school with a pickup truck, pick me up and a bunch of other boys, and he would take us out and throw us on the yearlings. We didn’t have an outside fence, just an inside fence. It was all cotton fields around. Every now and then, you’d see a horse or two takeoff through the cotton fields, with everybody hollering and screaming, ‘Whoa, whoa.’”

It was during these nascent stages of not only his life, but as part of his early development as a horseman, that Bray had a unique opportunity, one that still resonates as strongly with him today as it did during his youth.

“I rode races in the Ellorree Trials when I was 9-years-old, and wore a football helmet without a face mask,” said Bray. “But every summer, I would go to New England with my father, mother and family. We’d be at Rockingham Park, Suffolk Downs and Narragansett Park. I always got out of school a month earlier than the northern kids would, so I’d be the only one going to the racetrack usually. I would get a brand new pair of Kroop Boots every year. I was galloping horses at Suffolk Downs when I was 12-years-old. It just started from there. I loved to ride.”

New England’s Influence

The opportunity to learn about the Thoroughbred industry while being based in New England gave Bray a deeper prospective about racing, the importance of the horse and what it meant to be a horseman. There were no weekends or holidays off.

“It made me appreciate the ability of horses, even the cheap horses,” said Bray. “I ran horses for a claiming price of $1,500, where it was $900 to the winner. It was life or death with that horse. Nobody looked at that horse. You hated to show it to anyone because you didn’t want it claimed off you. You appreciated what a horse could do for you. You took excellent care of them. You appreciated the business and the hard work that goes with it.”

Every Saturday found Bray at the racetrack with his father, but had his mother had the prescience, she may have discouraged what at times became routine. Bray was getting an education, but in a different type of environment.

“Some days, my father would be giving me a ride to school, when we lived in Salem, New Hampshire, he’d say, ‘You want to go to the racetrack for a few days?’ I’d say, ‘Yeah, let’s go.’ Instead of school, I’d go to Lincoln Downs, Narragansett, and wherever he was racing at the time. My mother would find out a day or two later, when I didn’t come home from school. I was at the racetrack.”

A Mother’s Love

Bray’s passion for the sport was palpable, and his career as a rider was progressing as he was riding races in Maine at Scarborough Downs when he was 15-years-old. However, parental guidance would play a role in altering the course of his fate.

“The only way my mother would let me ride is if I promised to go back to school in the fall,” said Bray. “And when I got back there, she was feeding me like you wouldn’t believe. So, I went from race rider to football player in one year.”

Life Lessons

The racetrack provided a different type of classroom for Bray, as he gravitated toward the sport with an unrivaled enthusiasm, absorbing everything he could about the industry that would soon be all-consuming.

“During the early days, I was more or less learning about work, the work ethic and how the racetrack was an everyday affair,” said Bray. “The horses eat before you do. You take better care of the horses than you do yourself. That was a very important part that stuck with me. It was mainly the work ethic that was taught to me by my father.

“There’s a lot of things I remember doing, and him kicking me in the fanny, and telling me you don’t do that. I used to get away with murder. He schooled me pretty good most of the time.”

Opportunity Knocks

The early foundation Bray developed allowed him to establish a reputation as a competent horseman. He had been going to Ocala, Fla. to break horses in the winter. It was through a propitious set of circumstances that he would meet a Thoroughbred owner who would transform his life.

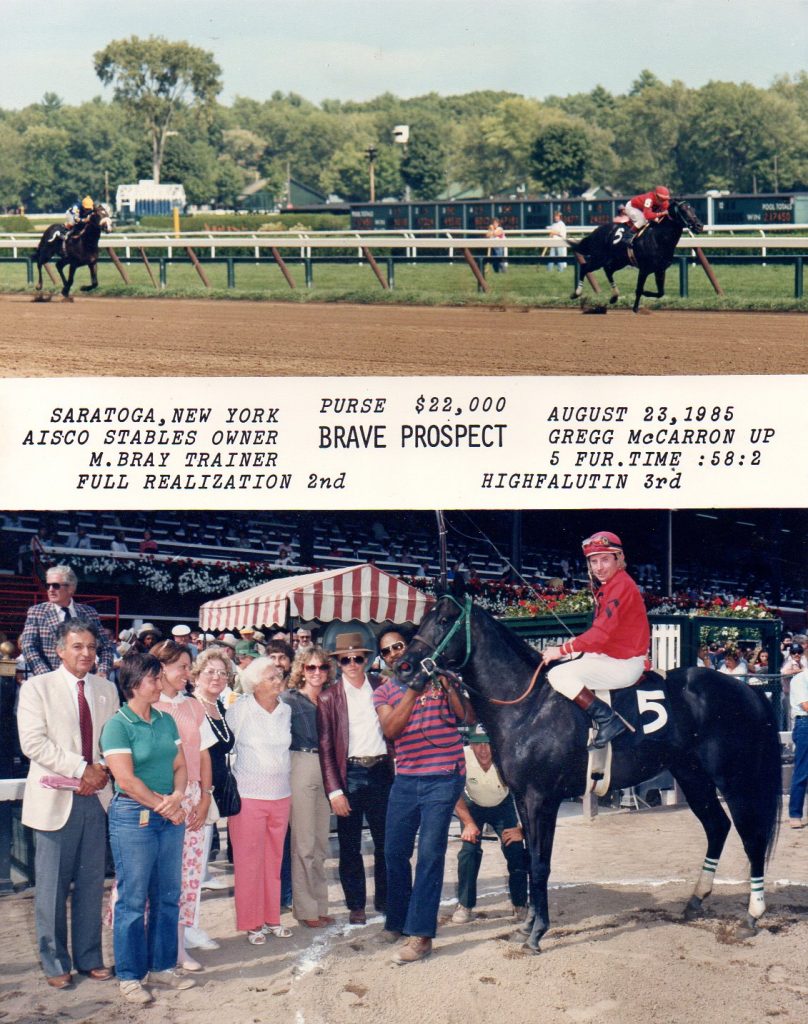

“A friend of mine was working for Butch Savin at Aisco Farm,” said Bray. “They had a really bad horse. She suggested to the farm manager that they call me to get on the horse. I went out, got on the horse and straightened him out. Pat Hunter was the farm manager at the time. He suggested to Mr. Savin that he should give me some horses to take to New England.”

Bray started with three horses for Savin and Aisco in New England, and he would eventually go to New York, taking over for Sally Baile.

“He would send me anywhere that I wanted to go with the horses,” said Bray. “I had 20 or 30 horses for him all the time. Jimmy Croll had the pick of the litter. We went for about five years. I was a private trainer for Mr. Savin.”

However, the vagaries of life would once again change the course of Bray’s, finding him in a different location for the next decade.

“My wife and I hadn’t had a day off, and I called up Mr. Savin and said, ‘I need a week off.’ He sent me a couple of weeks pay, and we went out to California for a vacation,” said Bray. “The day before we got back, Mr. Savin died. I went from 40 head of horses to one. He didn’t leave a will. The lawyers tied everything up. I could’ve kept training for him, but I wouldn’t have been paid for about six to eight months. I couldn’t carry a stable that large for that long. My wife and I went back to California.”

Powerful Bond

It takes a team for success at the racetrack, and Bray is no exception. His wife is the renowned Thoroughbred artist Sharon Crute, and the two have been each other’s biggest encouragers, providing support to one another at even the most challenging of times. Their relationship has overcome the adversity and pitfalls associated with the sport and business, of which there is no shortage, but they’ve managed to endure despite the challenges they’ve faced.

“She has always been my right hand,” said Bray. “I always trusted everything she told me. I knew she wouldn’t lie to me or try to cover anything up. If there was something wrong with a horse, she was the first to let me know. The same thing with the help, if there was a problem with the help; she was the first to let me know. She’d watch my back like you wouldn’t believe.”

The partnership between the two has been a critical component, with both having a deep understanding and passion for the sport and the business, one that’s palpable and resonates powerfully, as you can feel their emotion when talking to both of them about Thoroughbred racing. Crute’s experience as a horseman always made a significant difference in the operation.

“I had no problem with her taking care of the horses, and any time we had a problem with a horse, one that wouldn’t eat, that was too skinny, I’d give it to Sharon,” said Bray. “I would laugh because she would fatten it up for sure. She always took her time with the horses, and she’s done everything from being a hot walker to a racing official. She’s been a very influential part of my business. I used to get on as many horses as I could. It was important to have someone back at the barn like her all the time.”

Familiar Face

California would prove to be a fortuitous stop for the horseman. Bray and Crute would drive across country, leaving Hialeah in a brand new 5.0 Mustang with a monthly payment, a tent in the back and a pocket full of money.

“It took us about six weeks to drive across country because we would look at the map and say, ‘Let’s go here.’ When we got to California, Bobby Humphreys, who was a good friend of mine, and remembered me from The Meadowlands and Atlantic City, was the secretary at Golden Gate, and I told him, I needed a job.’”

Bray arrived at the racetrack in Albany, Calif. with $5 in his pocket, and told Humphreys, his need for employment was the overriding variable in the equation.

“I told him, ‘I don’t care if it’s driving the feed truck or working on the starting gate, but I need a job,’” said Bray.

Fate, connections and life’s vagaries would align, and Humphreys would provide Bray with a welcome lead.

“He (Humphreys) said, ‘Brian Webb just fired his assistant,’” said Bray, who had known Webb since he was 6-years-old. “I went over and saw Brian. He told me that if I showed up in the barn at 4 in the morning, I had the job.”

The two would enjoy a successful relationship including an impressive strike rate on the fair circuit in California, with Bray handling the string of horses, unseating Hall of Fame conditioner Jerry Hollendorfer as the leading trainer.

“When the fairs were over, I would go back and run the outfit for him,” said Bray. “I was with him for five years. Everyone told me that I wouldn’t last five weeks because nobody had previously. But we got along really well. Then, I went off on my own, claimed a few, started training, and I was getting on horses for Jerry Hollendorfer for years. When I went to Del Mar and Santa Anita, Jerry would send horses to me, and I would get on them for him. We had a good relationship as well.”

Home is where the Heart is

However, no matter where Bray was based, there was one circuit that always made him feel welcome. It was where he belonged, and that was New England.

He had the propitious opportunity to take some horses to New England for friends of his from Ocala, and he would return to Salem, N.H. and the familiar surroundings of Rockingham Park.

“The good thing about the east coast is that you’re kind of centrally located,” said Bray. “There are a lot of racetracks to run at. You had The Meadowlands circuit, New Jersey to New York, at the time you had the New England circuit and you weren’t too far away from Ohio. There’s a multitude of racetracks you could run at within a day’s drive. It was the Mecca of racing. Of course, I wanted to go back home too, because that’s where I knew everybody. California was nice, but it was expensive. You made a lot of money, but you had to spend a lot of money. I didn’t like it.”

A 4-year-old New York-bred gave Bray the biggest win of his career in 1988. Jimmy’s Bronco, a bay colt by Jet Diplomacy out of the Groshawk mare Flying Meet, captured the Grade Three Knickerbocker at Aqueduct on Nov. 8. Jean Cruguet rode Jimmy’s Bronco to victory. Jimmy’s Bronco raced in the silks of Mike Hanafin. The intrepid campaigner earned $136,750 in 1988.

“That was fantastic,” said Bray. “He couldn’t win a non-winners of two for $2,500 on the dirt at Rockingham Park. We put him on the grass, and he ended up winning the Brass Monkey series a number of times. He broke the turf record, and he did it again the following week. I took him to New York, to Aqueduct and Belmont and won a couple of races in New York (bred) company and open company, and decided to take a shot at the Knickerbocker. He won and the rest is history.”

However, Bray didn’t get to enjoy the moment, finding himself at a different locale, taking care of other responsibilities.

“At the time, I had 30 head at the Fair Grounds, and I missed the flight to go up to the Knickerbocker to see him run,” said Bray. “I never got a win picture from that, but I do have the tape of him winning the race.”

Keeping it Clean

The opportunity to compete in New England gave Bray a deep appreciation for horses who gave their all and weren’t competing at the highest levels.

“I saw a lot of the business that I wasn’t proud of,” said Bray. “I saw what horses with problems can do on medication, and I was totally against it, and it turned my stomach. I walked away from the business because I had some owners at the time that told me to win at any cost. I said, ‘No, that’s not me, I quit. I stayed away 15 years. And When the Water Hay Oats Alliance (WHOA) started, I was one of the first people to join it.

“The only thing that heals problems with a horse is time. Drugs aren’t going to heal horses; all they’re going to do is mask the problem. Think of yourself, say you hurt your back, and you take aspirin for it, something to alleviate the pain, and now you’re going to do things that you necessarily wouldn’t do if you could feel the pain. I want to know what the horse’s problems are and then correct them. I’m not against therapeutic medication when it’s used properly, but I’m against any medication being used on race day. I think a horse ought to run drug free, there shouldn’t be anything foreign to their system. There are too many ways to change the use of drugs and the making of drugs, the compounding of drugs to hide the problems a horse may have. It’s only that five % that you hear about doing that. The rest of the people really care for the horses, and we do use drugs therapeutically. If a horse needs Lasix if they bleed, it’s legal right now, you give it to them. However, I believe with the Horse Racing Integrity Act, it’s going to be where you’re not going to be able to race on any other drug on race day, and that’s the important part of it. Horses give us their lives.”

Pandemic Life Changes

Bray spent this past winter in Ocala, where he would run horses at Tampa, and is based this summer at Delaware Park. He had to follow a strict protocol at the Oldsmar, Fla.-based facility, where he had his temperature taken every time he went in and out of the gate.

“We had to wear a mask and gloves in the paddock, and for that reason, I don’t know of any cases of the virus hitting Tampa,” said Bray. “It’s the same thing at Delaware. They take your temperature every time you drive in the gate. They put a wrist band on you that’s a different color every day, and you have to wear a mask, and in the paddock as well…you’re offered an opportunity to run, so you have to take the precautions to keep the business afloat.

“We still have to feed these horses, take and care of them and pay your labor, whether you’re running races or not. The owners are getting hurt as well as the trainer. But even during the virus and the time there was no racing in New York and other tracks where horses were allowed to be, the horseman stood up and took care of the stock, and that should show people the integrity this business really has, where the horse actually comes first and people don’t believe that. That’s the public’s perception.”

Righting the Ship

The passing of the Horse Racing Integrity Act will help change the complexion of the industry, allowing for greater transparency and put an end to what many people within and outside of the industry see as questionable practices, those that tarnish the sport’s reputation.

“I think we should all support it (the Horse Racing Integrity Act),” said Bray. “Some of the biggest names are getting behind this. They realize what the public’s perception of racing is, and how important it is to have drug free racing. They have it all over the world, why can’t they have it here? There’s always going be somebody trying to find a way to cheat. They’re catching those people. They’re getting rid of them, and that’s the best thing they can do for the business…that’s where as horsemen we need to start speaking out, and (stop) being such a closed society. We have to stop worrying about stepping on toes.”

By Ben Baugh