Stage Door Johnny

Here was Stage Door Johnny, Breakin’ all of the rules, Stopping that Forward Pass, And taking the last of the jewels. He was a johnny-come-lately, Late to the show. He always started sedately, Then turned on the gas to GO.

Any discussion of 1968 comes with the need to cover its controversies and its historic moments. Assassinations of prominent figures. Protests. Movements toward social change. A war. In horse racing, the first Kentucky Derby winner to be disqualified and a resulting Triple Crown chase with problematic implications. Not unlike our own moment, 1968 was a year that brings up memories of challenge, heartbreak, and uncertainty. Inevitably the passage of time, though, brings us the chance to look back and see those involved with new eyes. We get to know them again, this time for what they have done outside of the heightened emotion of the moment.

In 1968, Dancer’s Image won the Kentucky Derby, but a failed drug test gave another horse the victory: Forward Pass. Then Forward Pass won the Preakness and suddenly a Triple Crown was on the line – sort of. What if Forward Pass won the Belmont? The Kentucky Derby already had its own asterisk for 1968. Would the Triple Crown, one of racing’s most elite and most difficult achievements, have one too?

Late to the show but deep in historic roots came a horse with a theatrical name that put on a show just in time. Here was Stage Door Johnny, a johnny-come-lately to the three-year-old scene, a horse that stole the spotlight and saved us from the question of asterisks.

The Show Starts Here

Helen Hay Whitney, daughter of an American diplomat and a railroad heiress, started Greentree Stable with a few steeplechase horses before World War I and then raced both over the jumps and on the flat until her death in 1944. Her husband Payne Whitney’s interest in Greentree came after the war; he eventually bought land next to his brother Harry Payne Whitney’s farm in Kentucky and thus Greentree Stud was born. There, they produced champions like Twenty Grand and Shut Out before Mrs. Whitney’s death in 1944. In the meantime, their children John Hay (Jock) Whitney and Joan Whitney Payson maintained their own breeding and racing operations, merging their equine interests with their parents’ after both Payne and Helen passed.

Like others in the Whitney extended family, both Jock and Joan heavily invested in first their individual stables and then in Greentree, continuing their family’s legacy in American horse racing. By the late 1960s, though, their silks, the watermelon pink with black and white vertical striped sleeves, had experienced something of a drought. While other legendary stables like Calumet were dominating the classics in the 1950s and 1960s, it had been nearly twenty years since Greentree had won the Preakness and Belmont Stakes with Capot in 1949. Their homebred champion Tom Fool had missed the 1952 Triple Crown season, but had gone on to win Horse of the Year after going undefeated at age four. Jock and Joan were anxious for another classic winner. In 1968, their last one would come from a most unexpected source.

Within Greentree’s band of broodmares was the flaxen-haired Peroxide Blonde. Jock Whitney had horses in both the United States and England and would import bloodstock from Europe to breed at Greentree Stud in Kentucky. Peroxide Blonde was a daughter of Ballymoss, winner of the Irish Derby and the St. Leger Stakes, out of the French mare Folie Douce. On the track, she ran only twice, winning once, but it was her pedigree and potential as a broodmare that were most important to Whitney. He bred her to Prince John, a stakes winner and early favorite for the 1956 Kentucky Derby. Their late May foal, a chestnut colt with a big white blaze, became Stage Door Johnny.

He was named for Jock, who had produced a number of Broadway plays, including A Streetcar Named Desire, and bought the rights to and then helped finance the film Gone with the Wind. In theatre parlance, a stage-door-johnny is a gentleman who would wait outside the stage door for actresses they wanted to escort and woo. The name seemed a natural fit for a colt sired by a stallion named for artist and actor John Barrymore and bred by a man who had an affinity for the theatre himself. Indeed, this colt was destined to put on a show, but it would take some growing pains to get there.

First Act

At two, the tall Stage Door Johnny got off to a slow start. He was a big, gangly sort of colt, the kind that take some time to grow into their frame and their ability. His only two starts came in late August and early September 1967, both races maiden special weights at 5 ½ and 6 furlongs. Stage Door Johnny finished second in both, carrying 122 pounds and jockey Heliodoro Gustines, who would be in the saddle for all of the colt’s races. With endurance in his pedigree and a long stride to boot, short distances were not his strength: he came from way back in both races, but had enough speed to finish second, which promised great things for the longer three-year-old races. He also seemed to have large ankles, and, in what seems to have been a preventive measure, Greentree trainer John Gaver had his ankles fired. He then sent Stage Door Johnny to the Greentree winter facilities in Aiken, South Carolina to prepare for his three-year-old season.

Though his colt had yet to break his maiden, Gaver saw potential in this son of Prince John. He pegged him for the mile-and-a-half Belmont Stakes early, confident that the colt possessed the speed and stamina necessary for that race. After all, his grandsire was Princequillo, who won the two-mile Jockey Club Gold Cup and set a track record in 1¾-mile Saratoga Cup. Later, Princequillo would be best known as damsire of one of the 20th century’s greatest horses, Secretariat. The only problem with Stage Door Johnny was that he was still an inexperienced racehorse, a problem which Gaver set out to rectify with more races.

On April 17th, Stage Door Johnny faced a field of eight others for a one-mile maiden special weight race at Aqueduct. He finished third in his first race back, still a maiden two weeks before the Kentucky Derby. Gaver ran him in another one-mile race for maidens on May 8th, just days after Dancer’s Image beat Forward Pass in the Derby and then was disqualified after the anti-inflammatory drug phenylbutazone, or bute, was found in his post-race urine sample. (Bute was illegal in Kentucky in 1968.) He faced another field of eight other maidens, carrying 114 pounds. He broke toward the middle of the pack, content to sit fifth until that final turn. Gustines powered him to the front and he drew off in the stretch to win by six lengths. Finally, in his fourth start, Stage Door Johnny had broken his maiden and done so impressively. Gaver’s assistant, his son John, Jr., called his father, who was recovering from foot surgery, to let him know about the breakthrough. “That’s our Belmont horse,” the elder Gaver declared. With four weeks to go, though, he needed to get at least one more race into his colt before that mile-and-a-half test.

The problem is, one does not find many longer races run in the United States, let alone that early in the year. Gaver settled for the mile-and-an-eighth Peter Pan, an allowance race for three-year-olds that later would regain its stakes status. Intended as a prep for the Belmont, the Peter Pan was set for May 23rd, three days after the newly renovated Belmont Park opened. Also in the race was Max Hirsch-trained Draft Card and T.V. Commercial, who had finished fourth in the Derby, both colts on the same path toward the Belmont Stakes as Stage Door Johnny. Gustines kept his colt behind the front-runners for the first six furlongs and then moved Stage Door Johnny around them in the stretch to pull away and win by four. The Peter Pan caught the attention of several trainers set to send their horses in the Belmont, including Hirsch, who thought that Stage Door Johnny should be second choice behind Forward Pass. Gaver, for his part, knew his colt had the potential to get that distance, but admitted that Stage Door Johnny was still a bit green. “I’d hoped to get one or two more races under him before the Belmont,” the veteran trainer admitted.

With time running short, though, the show had to go on, and Stage Door Johnny’s number was about to be called.

A Star Is Born

With the Belmont Stakes fast approaching, the possibility of a Triple Crown loomed and with it the questions about how history might regard Forward Pass. He had finished second in the Kentucky Derby, his victory coming because the horse that finished first was disqualified. How would history regard Forward Pass’s status as Derby victor? He had won the Preakness with a solid performance; ironically, Dancer’s Image had also been disqualified in the Preakness, after bumping horses when a hole he attempted to go through closed up as he was moving between horses.. Was Forward Pass worthy of adding his name to the pantheon of Triple Crown winners, twenty years after Citation became the latest horse to take all three? Or would the late-charging Dancer’s Image challenge Forward Pass one more time?

In the days before the Belmont, Dancer’s Image left the stage, after the same ankle issues that had necessitated the bute before the Derby returned after a workout. Fuller, unwilling to risk his horse’s safety, retired his hard luck gray colt. Despite his exit from racing, Dancer’s Image would remain at the center of legal wrangling over his Derby disqualification that would not be resolved for nearly five more years. With that, the storyline of another meeting between the two colts at the center of the post-Derby controversy ended and a new story arc began: who could challenge Forward Pass, now the Belmont’s clear favorite?

Enter our hero, Stage Door Johnny, dancing toward destiny. He was made the second choice at odds of 5-2 behind Forward Pass at 4-5. Behind him was the entry of Draft Card and Call Me Prince, both also cited as potential spoilers. Friday morning, Gaver sent Stage Door Johnny on a five-furlong breeze, covering the distance in 0:59 3/5. The veteran trainer counted himself pleased with the colt’s efforts, ready to send him to the post to try for Greentree’s third Belmont Stakes.

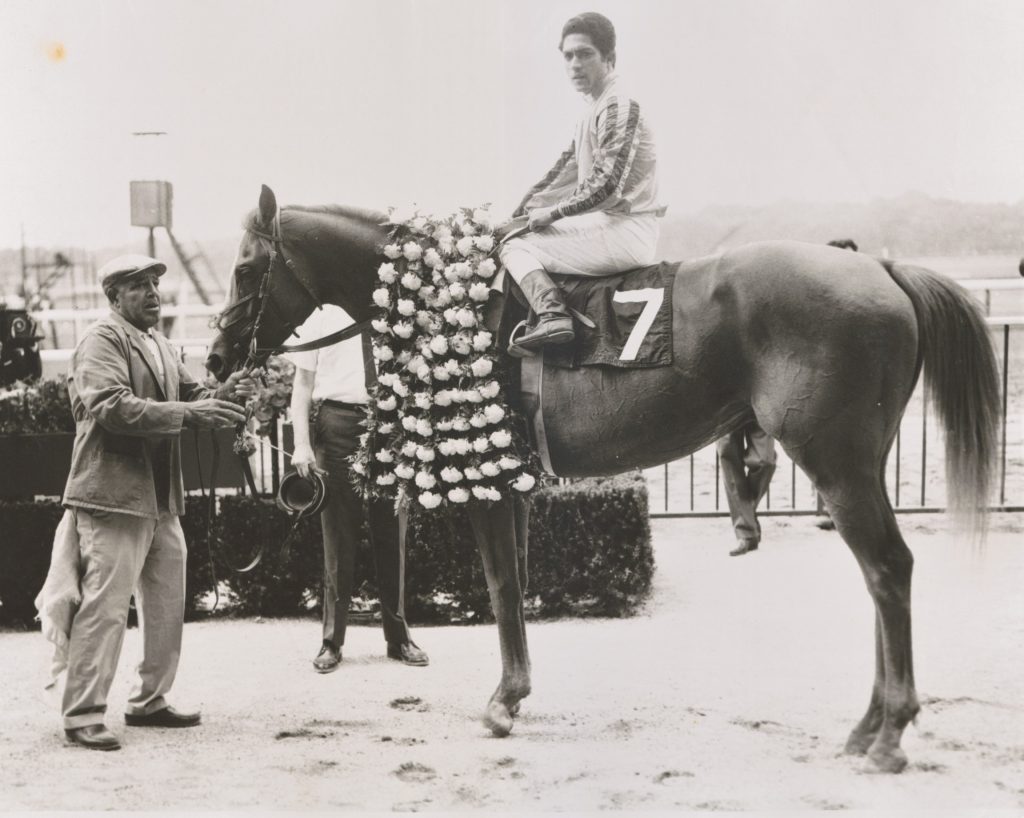

On a beautiful June day, the nine horses slated to traverse once around the mile-and-a-half oval trickled out onto the sandy loam, one on the cusp of history and the others there to try to spoil the show. As they loaded in the starting gate, Forward Pass took his place in the fourth stall and then Stage Door Johnny in the seventh. Clad in the Calumet devil red and blue, blinkers covering the slim line of white on his face, Forward Pass was ready to take his place in history, but twelve furlongs asks something of horses that few other distances do. Just as doubts about his legitimacy as a Triple Crown winner lingered so did the questions about his ability to go the distance.

For ten furlongs, Call Me Prince and Forward Pass ran at the head of the field, their pace moderate. At the head of that long Belmont stretch, Call Me Prince was done and Forward Pass was alone on the lead finally, but, on his outside, Stage Door Johnny was sweeping into the spotlight. Heliodoro Gustines had kept his horse toward the back of the field throughout the race, moving him up on the final turn and giving him the cue to go as they straightened out. Stage Door Johnny put on a show then, pulling even with Forward Pass, the two eye-to-eye down the stretch. With each beat, each stride, Forward Pass stalled: Stage Door Johnny by a head, then a neck, and then he was clear by a length and a quarter.

Twenty-three days after his maiden win, seemingly out of nowhere, Stage Door Johnny won the first stakes race he had ever run in and what a win it was. The Greentree colt was no longer an understudy: now he was a star.

Let’s Put on a Show

Stage Door Johnny had averted a crisis of asterisks and done so impressively, finishing the mile and a half in 2:27 1/5, the second fastest Belmont to that point. John Gaver was praised for his ability to take a lightly raced and admittedly still green colt and ready him for a race of this magnitude. Stage Door Johnny was not done yet either.

He followed up the Belmont victory with a turn back to a mile in the Saranac Handicap four weeks later. He faced five other three-year-olds as the 1-2 favorite in that race, carrying top weight of 126 pounds. Gustines rated him behind the leaders in fourth and then moved him to the lead in the stretch, passing Out of the Way with a furlong to go.

Two weeks later, Stage Door Johnny was back for the Dwyer Handicap at a mile and a quarter. Again, he was the high weight, 129 pounds, assigned one more pound than another potential starter, Forward Pass. The Calumet colt opted for the American Derby in Chicago instead, leaving the Greentree colt to face only five others, including Out of the Way again. Spotting his competition anywhere from six to nineteen pounds, Stage Door Johnny broke from the outside post, hung behind the front-runners until the stretch, and then turned on his usual closing speed to win by two lengths. It was his fifth win in five starts and his third straight stakes victory. This performance put him square in the conversation for the three-year-old championship, with Forward Pass also having some claim to that title. Gaver eyed a trip to Saratoga for his Prince John colt, with the Travers Stakes as his next act in this exciting show Stage Door Johnny was putting on.

His Final Act

In late July, with the Travers Stakes less than a month away, John Gaver sent Stage Door Johnny out for a workout in preparation for that prestigious stakes race. When the colt returned, the trainer found something amiss in his new star: a bowed tendon in his left foreleg. Just like that, the rising star who had gone from green to great in only a handful of races was done. Stage Door Johnny exited the stage for stud.

Chompion, bred by C.V. Whitney, Jock and Joan’s cousin, won the Travers on a sloppy Saratoga track, beating Forward Pass by 1¾ lengths. At year’s end, both Forward Pass and Stage Door Johnny shared the three-year-old male championship.

With his time on the track at an end, Stage Door Johnny ventured back to his birthplace, Greentree Stud, to start this next phase of his life. As a stallion, he sired 597 named foals, with 297 winners and 52 stakes winners. His daughter Class Play won the 1984 Coaching Club American Oaks and then his son Johnny D won the 1977 Washington DC International Stakes, a Grade I turf event, at Laurel Park. He also sired Late Bloomer, who won the Beldame Stakes, the Ruffian Handicap, and the Delaware Handicap in 1978.

At Greentree Stud, the paddock next to Stage Door Johnny’s housed another Belmont Stakes winner, Arts and Letters, who also had spoiled a Triple Crown in 1969. The two stallions struck up a friendship, racing each other in their adjacent paddocks and keeping each other company as older horses. When Gainesway Farm purchased Greentree Stud in 1989, the sale contract required that these two stallions remained in those paddocks, staying together until their deaths, Stage Door Johnny in 1996 and Arts and Letters in 1998.

In 2020, nearly twenty-five years after Stage Door Johnny left our scene, he still has a part to play in the story of the Triple Crown. He sired the broodmare Never Knock, dam of both Go for Gin, 1994 Kentucky Derby winner. Go for the Gin sired Gin Running, dam of the broodmare Tizfiz, sired by Tiznow, two-time Breeder’s Cup Classic champion. In 2017, Tizfiz foaled a gorgeous bay colt with a wide blaze that we all know as Tiz the Law, 2020 Belmont and Travers Stakes winner and now Kentucky Derby favorite. The story of Stage Door Johnny goes on, even after the curtain has fallen on this champion.

The show is done, the song a memory, Stage Door Johnny has quit this spot. He ran far and fast and spoiled a story, But Tiz the Law that he won’t be forgot.

Photo Credit: “Keeneland Library Thoroughbred Times Collection”

“This image is protected by copyright and may not be reproduced in print or electronically without written permission of the Keeneland Library.”