“My horse is faster than yours!”

By Franck Mourier

In the 17th century, British aristocrats were consumed by a feverish passion for horse racing. They would gather on their estates and challenge each other to races, shouting, “My horse is faster than yours!” The thrill of victory was sweet, but the agony of defeat was even sweeter: when they lost, they returned home determined to breed a faster, stronger horse.

As the competition heated up, wealthy racing enthusiasts imported horses from far-flung lands, hoping to infuse their stock with new blood and greater speed. These exotic stallions were mated with local mares from the Galloway and Irish Hobby breeds, producing a new kind of horse that was faster, braver and more powerful than any seen before.

The obsession of these men led them to all corners of the world in search of the perfect stallion. They scoured the deserts of Arabia, the mountains of Turkey, and the steppes of Russia, looking for a horse that could match their vision of speed and power. And when they found it, they spared no expense to bring it back to England, where it would become the cornerstone of a new breed of horse: the Thoroughbred.

The Thoroughbred breed was selected specifically for its athletic performance. Size, height, leg length, neck length, and color did not matter in the development of the breed. The only factor that mattered was which horse crossed the finish line first. The results of these races were used to test the potential sires and dams for future generations.

Breeders used the results of these races to determine which horses were best suited to pass on their bloodlines. In the words of Thoroughbred breeder Frederico Tesio, “The Thoroughbred exists because its selection has relied not on experts, technicians, or zoologists, but on a piece of wood:

The winning post of the Derby.”

In 1791, about 125 years after the formal establishment of the horse racing organization and ten to twelve generations of selective breeding, James Weatherby published the first General Stud Book. In this document, he established that the male lineage of all Thoroughbred racehorses could be traced back to only three foundation sires: the Byerley Turk imported in 1686, the Darley Arabian imported in 1706, and the Godolphin Arabian imported in 1729.

These three Eastern horses were bred by Bedouins in the desert environment and held in high esteem by Islamic people, who considered horses to be gifts from Allah to be revered, cherished, and worshiped.

Long before Europeans became aware of them, the horse of the desert had become essential for the survival of the Bedouin people. These horses were primarily used for warfare, as a well-mounted Bedouin could attack other tribes, capture their herds of sheep, camels, goats, and horses, and increase the wealth of his own tribe. War spoils, such as gold, silver, and jewelry were also valuable prizes.

Successful raids required the element of surprise, and the endurance and speed of the Eastern war horse were exceptional. These horses also needed to be brave, a trait that is still present in Thoroughbreds today. Horses with heart and determination will keep fighting, whether in battle or in a race. They will give their all, which is necessary for success in both situations.

In fact, the first of these foundation sires was a war horse, a Turkish horse that was referred to as the ‘’Byerley Turk’’ after his last owner, Colonel Robert Byerley.

the finest horses of the Ottoman Empire. Standing at 16 hands, he was taller than an Arabian and was known for his remarkable beauty, agility, and power. With a long back, plenty of bone, an elegant head with long ears, big eyes, and a commanding look, he was a prized possession.

The Byerley Turk was present at the Siege of Vienna in 1683 and the Siege of Buda in 1686, and although he survived both campaigns unscathed, he was eventually captured in Buda by some Englishmen who were fighting against the Ottoman Empire. The horse was then sent to England and became the mount of Captain Byerley.

With his new owner, the Turk spent two years fighting in Ireland and even took part in a race at Down Royal, which he won. This demonstrated his incredible speed and bravery, and he gained a reputation as one of the most famous horses in England. The Byerley Turk was known for his bravery in battle and was greatly admired by the English people.

However, upon retirement, Colonel Byerley was not interested in making money through stud fees and allowed the Byerley Turk to stand as a stallion for free.

The second foundation sire was the Darley Arabian, which was foaled in 1700.

The Darley Arabian was imported by two Englishmen, Wakelin and Brydges, who were breaking the Ottoman law of the time that prohibited the export of purebred desert horses. They were unaware that they were about to change the course of turf history as they secretly shipped the horse among bales of silk. The journey lasted five months without a stop, and it seems incredible that the stallion survived it.

The Darley Arabian was known for his elegance, with a bay coat, a large blaze, and three white ankles. He was considered a prize for his excellent bloodline, having been bred and raised by desert tribesmen.

The handling of Eastern horses was vastly different from the European approach, which was influenced by the Enlightenment and Descartes’ treatise that considered animals as mere machines to be subdued and governed. In contrast, the Bedouins showed incredible tenderness and affection towards their horses.

These men would cuddle them, bring them into their tents, into their parlors, to their tables, everywhere they would go, they would bring their horses with them.

The third foundation sire is the Godolphin Arabian.

There is ongoing debate among historians as to whether he was an Arabian or a Barb, and it still remains unclear until today where he was born. – whether in Tunisia, Morocco, or Yemen.

However, all agree that he was a gift from the Bey of Tunis to King Louis XV of France, along with a note that read: “Son of the Desert, he is strong and fleet with pure Eastern blood. He is descended from mares that once belonged to Mohammed. He is now yours, use him, he will strengthen and improve your breed.”

The King did not heed the advice and instead gave the horse away due to his poor condition. He was given to the cook to use as a cart horse. After several transfers of ownership, the horse ended up in the stud of the third Earl of Godolphin. There, he was considered too small and inferior compared to the larger European horses of the time and was not intended for breeding. Instead, he was used as a teaser to determine a mare’s receptiveness.

When a mare named Lady Roxana was brought to be bred with the stud stallion Hobgoblin, she rejected him. The Godolphin Arabian was then allowed to cover her instead, producing a foal named Lath, who went on to win the Queen’s Plate nine times out of nine at the Newmarket races. Lath’s full brothers Cade and Regulus, produced from subsequent matings with Lady Roxana, were also successful on the track and became good sires.

Although these three stallions were the foundation of the Thoroughbred horses, one lineage has dominated the breed for the past 50 years, while the other two are gradually disappearing.

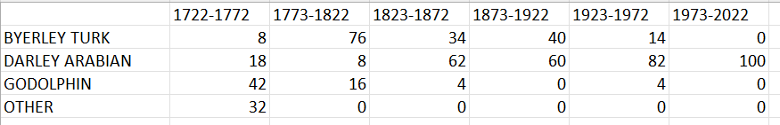

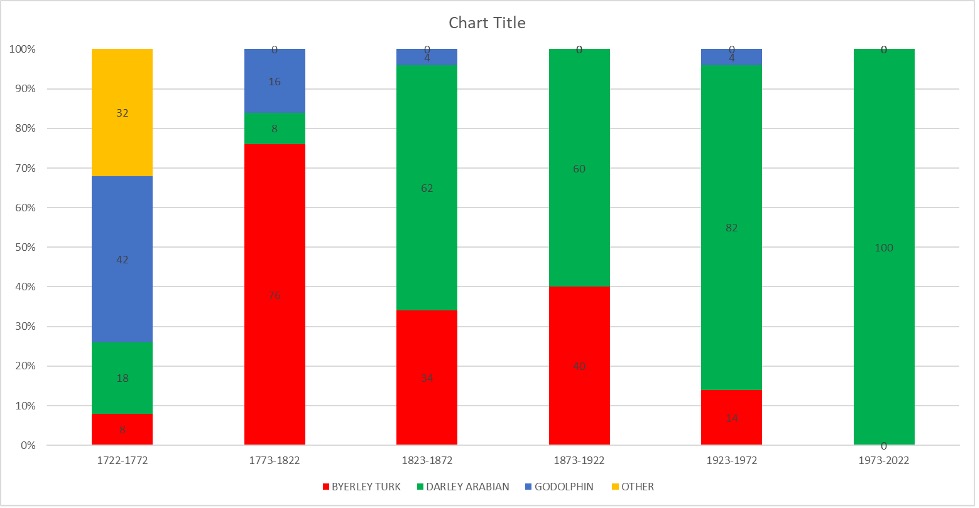

The following shows the percentage of stallions from each sire line that topped the general list by earnings in England from 1722.

During the first half of the 18th century, the breed was dominated by sires such as the Acaster Turk and Darcy’s White Turk, but these lines, shown in yellow below, quickly died out and were extinct by 1791, when the first General Stud Book was published.

In the 50-year period from 1773 to 1823, the Byerley Turk dominated the sire list, producing most of the prolific and consistent runners.

The official General Stud Book contained an error regarding the sire line of the 1875 Derby winner, Galopin. It is stated that he was sired by Vedette and belonged to the Darley sire line. However, rumors that Galopin was not actually sired by this stallion were circulating as early as 1874, (The Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News, 28 November 1874) and these claims were repeated in various Thoroughbred literature through the mid-20th century. (Famous Running Horses, Wall, 1949; Names in Pedigrees, Palmer, 1939), naming Delight as an alternative sire.

It is now established, once and for all, by recent forensic studies of gene sequence variations conducted in 2019 by researchers led by Dr. Barbara Wallner, that Galopin was indeed a son of Delight from the Byerley Turk line, not Vedette from the Darley Arabian line, as recorded in the General Stud Book.

In the present study, the accurate documentation has been taken into consideration and we considered Galopin the son of Delight.

Although the stallions from the Darley Arabian sire line are completely dominating the General Sire list nowadays, they were of minor importance during the first century of the breed’s development.

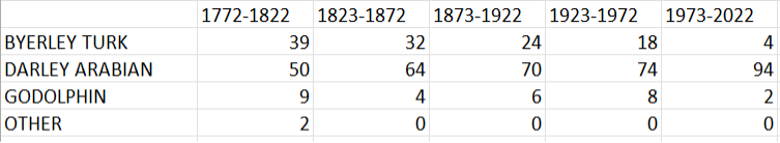

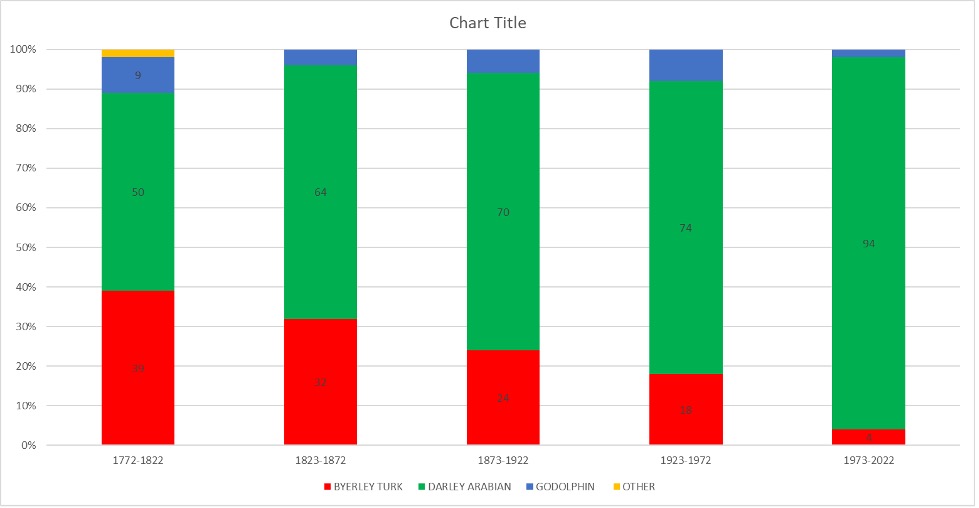

The analysis of the history of the sire line providing the winners of the Epsom Derby since its first running in 1780 tells a different story.

When brilliance is required for the top race of the calendar, the Epsom Derby, the Darley Arabian line was already showing its prowess from the start. Although only 8% of the top stallions in the sire list were from this line, they produced 50% of the Epsom Derby winners.

We can conclude that for a stallion line, pure brilliance, winning the Epsom Derby, is more important than producing solid, consistent runners in establishing a line with lasting influence. Those results confirmed the quotes and observations of Frederico Tesio that the breed has developed around the winners of the Epsom Derby and nothing else.

Over the past 50 years, the Turk and the Barb have been largely eradicated from the top line of the racehorse’s pedigree, and the Darley Arabian has achieved a complete monopoly, and it is not without consequences.

In 2018, Evelyn Todd published a fascinating paper in Nature analyzing the pedigree of 135,572 Thoroughbreds, titled “Founder-Specific Inbreeding Depression Affects Racing Performance in Thoroughbred Horses.” Todd found evidence that horses with more DNA alleles identical by descent attributed to the Byerley Turk line had greater cumulative earning, earning per start and career length. Conversely, these three parameters were negatively impacted when considering the Darley Arabian line. Todd speculated that some very influential breed shapers from that line like Bartlett’s Childers, Touchstone, and Stockwell had physical and temperamental issues that they passed on along with their tremendous racing abilities.

The dominance of the Darley Arabian bloodline has created a powder keg in the world of horse racing, producing horses that are more inclined to rely on their nerves rather than their physical constitution. Thoroughbreds from this bloodline have a strong vitality and need very little work, and strenuous training programs can actually do more harm than good. The ultimate edge of the Darley Arabian bloodline may not lie in their physical ability to avoid exhaustion, but in their mental ability to ignore it.

Soundness issues have become a significant concern for those involved in the training of Thoroughbreds. As Nick Patton, managing director of the Jockey Club estates, has observed: ‘Nowadays, with modern horses, the use of grass surfaces only takes place when they are in perfect condition.’

Gone are the days of the strong constitution of past Thoroughbreds, and the fragility of the present-day racehorse is a frequent observation of veteran horsemen and experts.

“Horses today can’t stand the hard training. They don’t have the constitution,” said Bud Delp, who won the 1979 Derby with Spectacular Bid. “But I can’t tell you why.”

Mill Reef’s trainer Ian Balding declared recently “Sadly the modern Thoroughbred has become much more fragile than it used to be.”

“The brittleness of the modern horse is a problem that is getting worse all the time and one for which racing seems to have no solutions.” remarked recently Media Analyst Bill Finley.

Jonathan Stettin of Past The Wire stated:

“Horses race less and don’t have the longevity they did in the past. This has continued to be the trend as far back as I can remember, at least since the 70’s.”

Andrew Beyer acknowledged in the Washington Post:

“The facts are irrefutable. In 1960, the average U.S. racehorse made 11.3 starts per year. The number has fallen almost every year, and now the average U.S. thoroughbred races a mere 6.3 times per year. Almost every trainer whose career spans the decades will acknowledge that thoroughbreds aren’t as robust as they used to be.”

Believe it or not, training and racing top-notch thoroughbred horses requires surprisingly little exercise. These descendants of the Darley Arabian are able to achieve peak fitness levels with only a handful of workouts per month. In fact, it’s not uncommon for these equine athletes to race just once a month, sometimes even less! Between races, they may only reach top speeds once or twice, and even then, only over short distances – think half a mile or less. So what do they do the rest of the time, you ask? Well, they’re exercised at a leisurely gallop for a mile or a mile and a half, and no more. And in the days immediately following a race, they’re given a well-deserved rest and only taken out for leisurely walks. It’s truly amazing how little exercise they need to perform at the highest level.

You may think that the job of a trainer is to make horses go faster. In fact, it isn’t.

The job of a trainer is to make horses go slower.

No horse, even a champion, can run for more than ⅜ to half a mile flat out at maximum speed. The classic distances are from a mile to a mile and ¾. So in order to win those races a horse needs to learn to be rated.

The trainer’s job is to preserve this ‘’supreme nervous energy’’ that they inherited from the Darley Arabian which must be nurtured and never sapped.

We can conclude with this beautiful Arabian quote that fits so well with the descendants of the Darley Arabian:

‘’Forget your legs,

Forget your hands,

Ride with your heart.’’

Photo: Franck Mourier, Franck’s 16 year old daughter riding out for Alan King in preparation for Cheltenham