Fuller’s passion produces powerful partnerships.

It was love at first sight for Abby Fuller.

Her story wouldn’t be all that unusual, a young girl is introduced to horses, has riding lessons and gets caught up in the romantic allure associated with a majestic animal renowned for its beauty, power, and speed. However, not too many of those young girls would grow up and become a professional athlete and pioneering female jockey, riding head-to-head with her male counterparts, at a time when chauvinism was far more accepted, yet she still enjoyed success that included riding a champion filly that has been enshrined in the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame.

“My mom and dad both liked horses.,” said Fuller. “Dad (Peter Fuller) already had racehorses when I was a kid, but I didn’t know a whole lot about that until later. I definitely had a horse connection. All the kids in my family, got to meet horses and have some riding lessons. I was definitely the one who was most into the horses.”

Sweet Memories

And for Fuller, horses were life, and it manifested itself in different ways. Childhood brought with it an opportunity to explore the vastness of one’s imagination, but it was something that would eventually evolve into reality.

“I had a little play barn instead of a doll house,” said Fuller. ”We had a doll house, but I loved the barn. I had little horses, one was actually a tiny little wooden horse; I had one that I called Black Velvet, and they had names on their stalls, little buckets and I can still picture it in my mind.”

Bitten by the Bug

Fuller would start riding at age six, going for riding lessons once a week during the spring. As she grew older, and reached age nine, she began riding at September Farm in Rye, N.H., laying the foundation for what was to come.

“Me and my two younger sisters would go for lessons, and then I would stay whenever I could,” said Fuller. “I’d get to stay at the barn and kind of do work. I had a few friends there, and it was kind of a gang of us. Sara Colbert, the farm owners’ daughter, taught us how to take care of horses, and eventually we took out trail rides. I loved it there. My sisters often went off to the beach, and I’d be, ‘please let me stay at the barn.’ We would go a few times a month, and then I ended up getting an off the track Thoroughbred, when I was 12. And she was kind of wild, but she was cool, she taught me a lot.”

The name of the horse that was Fuller’s school master was Rip Leader, a 3-year-old filly that the trainer had found in New York.

A Life Changing Event

Her parents had a summer home in North Hampton, N.H., and a racing oval 35 minutes away in Salem would play a role in the aspiring horsewoman’s future. However, the younger Fuller didn’t have too much knowledge about the sport of Thoroughbred racing, other than the fact that her father owned racehorses, but that all changed when she was nine and had the opportunity to go to Churchill Downs and experience the first Saturday in May.

“I was the youngest of the kids that got to go because of my intense horse interest,” said Fuller. “What else was I going to end up doing? When you first see the Kentucky Derby. That’s the first horse race that I remember seeing as a kid. What a way to get introduced (her father’s horse crossing the wire first). I can’t imagine. I was there and I said, ‘I’m going to be a jockey.’ No one even told me there were no women jockeys in 1968.”

Fuller’s father’s horse, the ill-fated Dancer’s Image won the first jewel of the Triple Crown, only to be disqualified because of having phenylbutazone in his system. However, her interest in becoming a jockey increased markedly after being exposed to Thoroughbred racing, becoming all-consuming in its nature, as she evolved as horsewoman, working diligently to hone her skills with show jumpers and hunters.

”Obviously, to see your dad’s horse win the Kentucky Derby, it was pretty amazing (emphatically),” said Fuller. “It’s funny, I just remember saying that ‘I’m going to be a jockey.’ Then, a little later when we were learning jumping and all that, that’s when Kathy Kusner from the Olympic team, and she was a great hero, goes to court in Maryland, for the women to get the right to ride, and all the early ladies were absolutely my heroes. Kathy of course, Diane Crump, Barbara Jo Rubin and Penny Anne Early, and I read all those articles. Tuesdee Testa, and then of course later on meeting a few of them. They were heroes. And years later, of course riding with Denise Boudrot, who was one of the first New England women riders. Mary Ann Bogachow, Mame Clayson, Joanie O’Shea, we had some great New England people, and even women who just worked on the backstretch, training.”

Inclusion and Inspiration

The women who worked on the backside of the racetrack served as role models for Fuller and other aspiring horse women, and not just the jockeys, the trainers, assistant trainers, exercise riders, grooms and hotwalkers, all had inspirational stories, and their passion for the horses were palpable.

“New England was always a place where you could get a shot there, if you worked hard, which was a cool thing,” said Fuller. “And in having the opportunity to be there, you heard a lot of good hard work success stories for people who just kept showing up. And even when you think back, Bill Veeck, Lou Smith and the guys who promoted at both Rockingham and Suffolk, they would have these promotional races for women to kind of build it up. That’s pretty cool. I think they were some of the first ones to really embrace it. I love that part of the New England racing history, and then to get to be part of that (emotional).”

School Days

However, Fuller did contemplate participating professionally in another equestrian discipline, prior to making her transition fulltime into the world of Thoroughbred racing. She was matriculated in a learning institution, where the focus was not only on scholarly pursuits, but provided her with the opportunity to direct her energies toward her passion, allowing her to build upon her foundation, gain invaluable confidence and help set the tone with those initial resources that would be critical components as she pursued her vocation.

”I did (have eyes on being a show jumper), and I was really fortunate the last three years of high school,” said Fuller. “I went away to a boarding school in Greenfield, Mass., Stoneleigh-Burnham School. Its focus was on academics. But there were horses, and there was a barn right on the property. They actually had different disciplines, show jumping and eventing were big focuses. There were kids with western horses, so to have that opportunity with having my horse with me at school and to be able to ride every day was advantageous.”

The school also provided Fuller with the opportunity to work with several outstanding instructors who had competed at the elite level and were able to impart their knowledge and horsemanship with the students.

“We had a couple of excellent horsewomen that ran the program there, Cindy Ferguson and Dana Douglas, they came from big time show jumping with Victor Hugo-Vidal, who was their trainer and brought their level with them to the school. And Peggy Dils was this great eventing lady. Peggy was already there, and then Cindy and Dana came as I came. It was kind of their first job in the industry. They upped the game.”

Show Rings and Racing Dreams

And as she progressed, Fuller found herself going up the levels, qualifying for more prestigious competitions as a hunter/jumper rider. But the idea of the racetrack was something that was still on the horsewoman’s mind.

“So, the last couple of years that I was a junior rider, 18 and under, we went to bigger and bigger shows all through Connecticut,” said Fuller. “We went to the Saratoga Show. So, the first year as an amateur, I was 19, my dad was very gracious, and he said, ‘are you going to do the racing?’ I taught kids riding and worked at the farm, but that in no way covered getting to do the big shows. It was amazing. I did amateur hunters, and I did preliminary jumpers.”

There were two horses in particular that would play a role Fuller’s success on the hunter/jumper circuit, making the experience far more satisfying, allowing her to participate against some of the best riders in the nation. And it was the Thoroughbreds who would teach the aspiring jockey how to ride. She rode in Florida, missing the blizzard of 1978.

“We got a horse that had been donated to the school, and he and I formed a really cool bond, and did some amazing jumper stuff. His name was Cougar (the horse Fuller did equitation and the jumper preliminaries on),” said Fuller. ”I had a neat mare that Cindy and Dana found in Connecticut in a backyard and her name was Breezy Affair. We actually qualified for Harrisburg and Washington, the last year I got to show. We got to show in Ocala, when HITS was at the Golden Hills Academy. The school that was the show grounds. We did that, and then there was a show in Tampa. It was really neat, and a little different. Wellington was just being built.”

A Breed Apart

Thoroughbreds were the go-to breed for hunters and jumpers back in the 1970s, so it wasn’t surprising that Fuller developed deep connections with the horses she rode.

“When I left, there weren’t really Warmbloods,” said Fuller. “That wasn’t a thing, Michael Matz and Rodney (Jenkins) rode Thoroughbreds (both elite show jumpers and currently Thoroughbred trainers), all the hunters were Thoroughbreds too.”

Problem Solver

One horse in particular Fuller seemed to be the right fit for, providing insight into her promise as a horsewoman, as she was able to get the best out of a gelding who had been donated to Stoneleigh-Burnham. The horse had a proclivity for doing something that was extremely unproductive, but Fuller seemed to possess the innate talent to unlock the horse’s potential.

“Cedar Lodge (Victor Hugo-Vidal’s farm) donated Cougar to my school. He used to stop with the girl that got him,” said Fuller. “That was the place where they would show up to ride, the kids, but maybe they didn’t interact with the horses. So, they donated him because he was stopping.”

However, no one mentioned anything about the stopping. The connection for the donation was that Dana Douglas and Cindy Ferguson used to ride with Victor Hugo-Vidal.

“I rode him and kind of really got along with him,” said Fuller. “Of course, at the school, we took care of him ourselves. We would brush him graze him, anyway, we had a great connection. I end up showing him, and one of our first shows is at Eastern State and Victor was the judge. Cougar was a Thoroughbred and had those beautiful golden eyes. I don’t know his pedigree and I don’t know if he ever raced. Anyway, I end up showing him and he was great. It was an indoor ring at Eastern States, and there’s a lot of excitement and it tests you a little bit. So, Victor’s judging and he came up to Cindy after one of my classes, and goes ‘what did you do to that horse?’ and she goes, ‘What do you mean? We love him. He’s great.’ He goes, ‘He was a stopper. He was stopping with the kids.’ She was like, ‘Really? We didn’t know that.’”

The two became inseparable with Fuller purchasing the horse, after she graduated from school, and they would exhibit at the preliminary jumper level.

“In his later years, I gave him to Cindy my instructor,” said Fuller. “Her niece rode him. All of my horses’ kind of stayed somewhere I didn’t really sell them. I gave them to good homes to my friends who would keep them. Actually, I had the opportunity to ride Cougar many years later. I was a jockey and would go to visit, ride him again and that was fun.“

A Breed Like No Other

Another horse from Fuller’s past that was scopey and athletic enjoyed a career on the racetrack and was sired by a horse that was owned by her father.

“The one horse that I had, who was a son of Dancer’s Image, his name was Tumble the World, who was a steeplechase horse in France,” said Fuller.

Resonating Relevance

Fuller had the opportunity to rub shoulders with Gene Mische and Cornelia Guest, and actress Linda Blair was riding at that time. Those experiences still resonate with the horsewoman, and are deeply rooted in her conscience, allowing her to revisit her past, which in turn has become her present.

“I had a great friend, Dorli Ruegger Burke, and she’s back showing again as an amateur, so I connect with her a few times a year and see her ride. It rekindles memories and allows me to remember back when, and I still have some dreams of getting myself back fit enough to do a little jumping. Kind of go full circle, which is the name of my farm in Ocala.”

Career Decision

However, Fuller’s focus began to shift, and knew the transition to the racetrack would take some time. She left the hunter/jumper world and would go to the barn of a veteran horseman to start the process, one that was less seamless than she had envisioned.

“When I first went to the track, I went out to Norman Hall, a great old-time horseman in Massachusetts,” said Fuller. “His son was John Hall, who was the farm manager for many years at Taylor Made. His granddaughter is Amiee Hall who is a trainer in the Mid-Atlantic. But Norman, he was into show horses, but they were also breaking some racehorses out at their farm in western Massachusetts.

“I started going out there and the first horses I got on, dad actually had some Mass-breds that were getting broke out there, and one just ran away with me. I had no clue. I kind of honestly thought, ‘hey I’ve been riding all my life now, I’m going to be good.’ I had another thing coming. I had a whole new learning curve, which was great, which is one of the great things about horses.”

The Thoroughbred industry would be a powerful teacher, and one of the lessons Fuller learned was humility as the transition from the hunter/jumper world offered its own series of challenges. But those early experiences would prove invaluable, helping in ways she didn’t anticipate.

”It was kind of funny because I thought, I already knew how to ride (laughing),” said Fuller. “And then he saw me alright, and I got dropped, during one of the early days by a sweet 2-year-old. He went to drop his head, buck and play a little, and then put me back on the end of the shank. It’s great. You get humbled. I learned kind of the old school way. It took a few years, starting with the young horses, which I think was really helpful. A lot of the girls started with show jumping, and I always thought that made me good out of the gate. I was good out of the gate.”

Initial Experiences

Her indoctrination to the racetrack began in 1979, where she worked for trainer Ned Allard who had several horses for her father.

“I started walking hots and cleaning tack, learning to gallop,” said Fuller. “We were at Rockingham, actually the year that the grandstand burned. I’m thinking that was 1980. And then each winter for the next two or three years, I would come to Ocala and start the young horses at different farms. I worked at one time for Norman Casse at Cardinal Hill, I worked with Margie, Billy and Jimmy Baker who all taught me a ton. I worked at the OBS Sales.”

Ocala provided Fuller with several opportunities, allowing her to hone her skills and learn what was to be expected when she did finally ride in her first race at the racetrack. However, it was those early experiences that provided a unique foundation, instilling in her a sense of confidence and belonging, that she had found her niche and there was no going back.

“I actually rode a couple of Arabians for my first actual horse race experiences out at Murty Farm, and then at OBS, and won a race at OBS on an Arabian,” said Fuller. “I still remember him, a big pretty gray stallion. That was fun. The first race I rode out at Murty, I rode some filly, and the guy goes ‘where’s your overgirth?’ I said, ‘What’s an overgirth?’ And the saddle slid back and went under the horse, and I went off. It was kind of an amazing. That was actually my first official horse race. I had a friend there from the show jumping world, she was a good photographer and took a whole album of pictures. It kept clicking as it all unfolded. There was no thought of, ‘Oh my God, I can’t do this.’ Okay, now I have to learn some more stuff.”

The experience itself was one that was a bit unorthodox but provided the aspiring jockey with a far deeper perspective as she navigated her way through the channels. One thing was for certain, Fuller never had a problem making weight for a race.

“I probably weighed 99 pounds soaking wet,” said Fuller. “They literally dropped pieces of lead down inside my boots to make me weigh more. I didn’t have a lead pad. I didn’t know what was happening, but it was great. I loved it and I wouldn’t trade any of it. It’s so neat now, coming back to Ocala, again that full circle thing, living here and being here, and see it really growing up, with the World Equestrian Center and the other venues. It’s pretty amazing.”

Realizing the Dream

Fuller began riding as an apprentice jockey in the fall of 1982, but earlier in the year, she had become farther immersed in the industry.

“I think it was like November, I rode my first race at Suffolk Downs,” said Fuller. “I didn’t win a race until July 1983. Before that, all during that earlier time in 1982, I was still galloping, I was on his (Allard’s) payroll, and he was great.”

Lost Opportunity

However, now having reached one of her objectives, she directed her energies toward a more defined purpose, with securing more mounts in the ultra-competitive world of Thoroughbred racing being one of those goals. The vagaries of the sport, rider changes and personal preferences of owners were among the variables that were commonplace and would take some getting used to.

“I would get done (galloping), and I would try to hustle around the barns and then as we were getting into that spring of 1983, I said to myself, ‘I need to ride more.’ I had ridden a horse for Ned, and I finished third, he had been off a little while. I still remember his name, Angel’s Sail, a big black beautiful horse, a little heavy-headed, probably a little bit too much horse for me to ride, and I finished third. And then Ned took me off. I think the owner said something. And then the horse came back and won with Carl Gambardella, our leading rider (the leading rider at Suffolk Downs) on him. ‘I was mad. I wasn’t happy. I can’t believe it, I could’ve won on him, blah, blah, blah…’so, I told Ned, ‘I have to quit, I’m going to go out and hustle rides.’ He said, ‘okay.’ And by now I had been working for about three years for him.”

Changing Barns

Fuller would find herself landing in a good spot, working for a conditioner with a good reputation, and it was through a propitious opportunity that she found herself securing mounts after taking the leap of faith. That chance led to eventually riding for a horseman enshrined in the New England Turf Writers’ Association Hall of Fame.

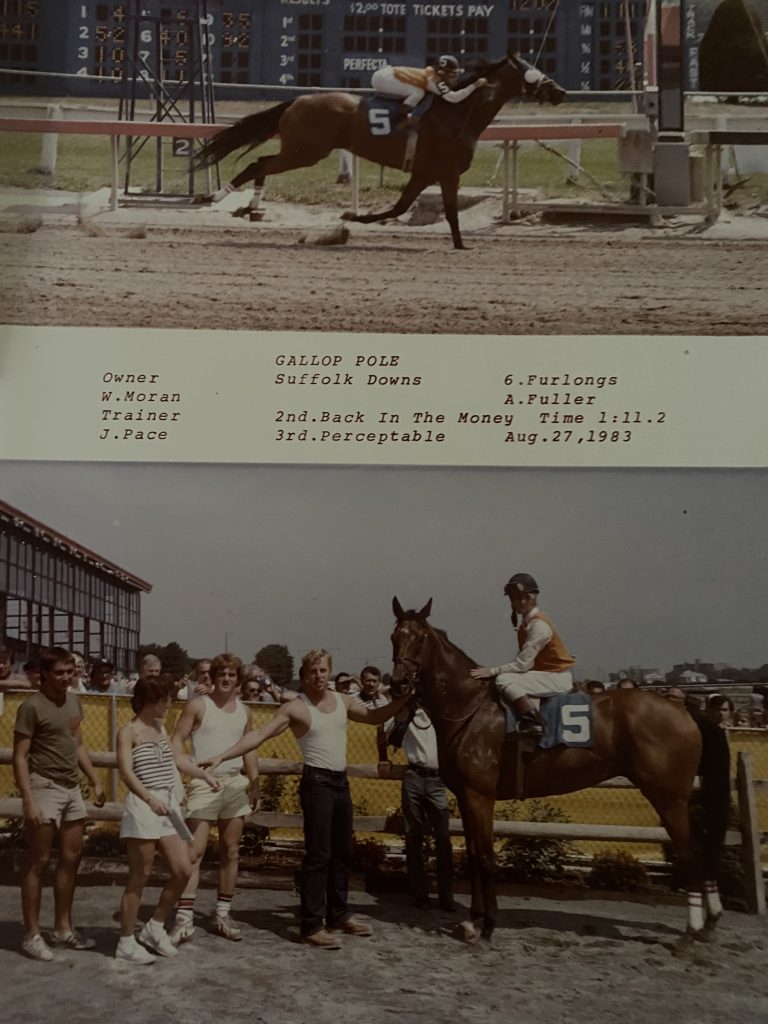

“I was in Jimmy Pace’s barn, a great guy and a classic New Englander,” said Fuller. “I kind of walked by or he walked by, and he said, ‘does anyone know a bug rider who wants a chance.’ and I stopped him and said, ‘I do.’ And he said, ‘I have a horse to put you on’ So, on July 3, 1983, I got to ride Gallop Pole and he won. It was an absolute thrill, and I ended up winning about five or six on that horse over a few months, several for Jimmy and then I got to ride for Billy Perry.”

Gallop Pole would be a steady source of pride and income for Fuller as she found herself in the winner’s circle with the hard-knocking claimer that William Perry would take for a tag. The horse would gradually climb its way up the ladder, but Perry opted for another rider initially, selecting the leading apprentice rider Jack Penny over Fuller.

”I kind of kept bugging him to give me a shot,” said Fuller. “I loved the horse, he loved me, and I do think you have a connection with certain horses. And with him being my first winner, I had known him for a while from being at Jimmy’s (Pace) barn. Jack (Penney) didn’t win on this horse, and Billy finally gave me a shot on him, and he won. That’s how I first got to ride for Bill Perry as a bug girl and that was a lot of fun.”

Arkansas Bound

A change in locations for the winter, seemed to be in order for the apprentice rider as Fuller made the shift in her base of operation to the southwest, allowing her to make new connections, learn from some of the nation’s best riders and be exposed to some new experiences that would be part of her evolution process as a horsewoman.

“I went to Hot Springs (Oaklawn Park) that winter, with Dad’s blessing,” said Fuller. “He said ‘Go.’ Suffolk was tough, we raced all year round. New England racing in the winter, as anyone who’s been there and who’s done that knows it’s not an easy game. He kind of sent me on my way. A good friend of mine was headed out there. I thought, I’ll get to learn a lot. That’s when Pat Day, John Lively and Eddie Delahoussaye were there. Mike Smith may have had the bug or just lost it. It was an amazing time to be out there. I frankly did not get a lot to ride, but of course, I watched everything.”

However, before meet’s end, Fuller found herself with the chance she had been waiting for, and didn’t disappoint, with her patience and persistence paying off.

“I did get to win a race for a guy who was an Arkansas guy who had been in New England,” said Fuller. “And so, he gave me a shot on a filly Cold Cash Gal, and we won there.”

Basking in the Bluegrass

One propitious chance would lead to another, and her time in Hot Springs would allow her to secure a mount that would take Fuller to a racetrack most jockeys would aspire to ride at, providing her with a chance to showcase her talents to a broader audience of horsemen.

“I got an amazing opportunity through a great friend of mine Mary Ellen Hickey,” said Fuller. She was a really good super rider. She was from Kentucky, galloped for Lynn Whiting and she had gotten a little bit heavy for race riding. She had a friend, Lee McKinney who was training horses. Mary Ellen said, ‘Give my friend Abby a shot. You know, she’s got the bug.’ I rode the horse and she finished third. Nutty Grapes at Hot Springs. She said, ‘I’m taking this horse to Keeneland, and on opening day there’s a race. Do you want to go?’ I was like, ‘Do I wanna go?! Heck yeah!’ It ended up being the first race, opening day of Keeneland in 1984. And I got to win on Nutty Grapes. It was so much fun. We went out and celebrated at the Irish bars. We had a ball. It’s the only race I ever rode there. It was so cool.”

She stayed in Kentucky to watch the Run for the Roses at Churchill Downs, and then returned to her home base, Fuller’s experiences at Oaklawn and Keeneland, along with her new agent Jackie Moore, who had previously had Jack Penney’s book, suggested far bigger things were on the horizon. The two formed a formidable combination, with Fuller achieving at an optimal level as the leading female rider in the country.

Hall of Fame Talent

However, it was not too long after this success that Fuller would have the opportunity to ride the horse of a lifetime, a Triple Tiara winner, 3-year-old filly champion and eventual inductee into the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in Saratoga Springs, N.Y.

“And amazingly, then along came Mom’s Command,” said Fuller. “That did happen quick and early on in my career. I was so blessed; and it was also partly good that I didn’t really know what was happening. I just kept going and showing up to ride (laughing). We always knew and had high hopes for her. We knew, and that kind of speaks to her first start in a stake up at Rockingham (the Miss Faneuil), of which I was not aboard. I was on days (having drawn a five-day suspension).”

The chestnut filly by Top Command, out of the Pia Star mare Star Mommy was ridden to victory by Benny Carrasco in her first start, breaking her maiden at first asking. The Ned Allard conditioned future hall of famer was bred and owned by Peter Fuller.

“She actually broke real slow, green and just kind of blew by everybody in the stretch,”’ said Fuller. “She was a longshot, being a first-time maiden in a stakes race. And there was a really nice mare at that time, Sheer Ice who was well-bred. A nice filly. But after two starts against Mom, the owners weren’t running against that one anymore. So, they looked for other spots. But then Mom came to Suffolk and we won the Priscilla Stakes. That was her second start. She was a horse that never ran in anything but a stakes race, which is pretty cool.”

It became obvious that Mom’s Command was poised for a larger stage, and Fuller and the daughter of Top Command would go to Elmont, N.Y. to run in the Grade Two Astarita Stakes, adding to her growing list of accomplishments, helping to set the stage for what was to come.

New experiences and a modified approach would make the juvenile filly less apprehensive, and she would respond accordingly.

“She had a habit of breaking slowly, mainly because she was just a baby girl and she would get a little pensive in the gate,” said Fuller. ”Once they got her to New York, Bob Duncan at the time was the assistant starter, and he went right in the gate with you. But he started working with her. He rubbed her head, and turned her head off to the side, and she really started to learn to relax. Once she relaxed and could break with everybody, her natural speed took her. She was never playing catch up anymore. So, that made her just so tough.”

However, the vagaries of life would mean changes were on the horizon, and there would be a different rider on Mom’s Command in her next start at Laurel Park in a Grade One stakes race.

“Greg McCarron rode her in the Selima,” said Fuller. “She did win, but I always thought there was a little bit of a battle. Greg obviously has a different style of riding than me. I think they wanted him to kind of try to rate her, like we’re going to teach her to slow down a little bit. She really wasn’t about that. She was about ‘this is what I do, and you get along with me, and you help me.’”

Some things are immutable and can’t be changed and the ferocity and determination possessed by the multiple stakes winner was unwavering, and Fuller’s bond with the filly gave her insight into the character of the future champion. Fuller’s experiences and keen observation served her well helping her navigate waters that she hadn’t chartered before and in doing so allowed the combination to achieve at the highest level.

“My thing with her, I definitely took my feet out in front of me took and took a long hold along the bottom of her neck, which a couple of great old steeplechase guys, Vern Smith and Tony Cataldi, who was a really super trainer in New England, taught me about rating a horse without fighting them,” said Fuller. ”And getting to watch guys like Pat Day out in Hot Springs, I definitely learned how to manage a horse. She wasn’t the kind of horse you were going to reach up and grab a hold of and tell her she’s going to go in 24 and change. That’s not really who she was. We learned a lot together.”

Peter Fuller had thought about running Mom’s Command in the Breeders’ Cup, and her next start would come on the west coast at Hollywood Park in the Hollywood Starlet to cap off her juvenile season. But a less than ideal post position would factor into her performance.

“So, we ran in the Starlight for 2-year-old fillies, and we were literally on the outside rail at Hollywood with all our speed,” said Fuller. “We got hung out, though she made a gallant effort to finish fifth. There was a big field. I believe they changed the distance too, because we were literally sitting right before the turn and the outside fence. It was pretty much a no-win situation. She definitely gave a great effort to show that she certainly belonged in that caliber.”

Mom’s Command took the winter off and her respite from the races seemed to pay dividends for her sophomore campaign. The filly would win seven races including five consecutive scores that included the Triple Tiara en route to year end honors as the outstanding 3-year-old filly.

“She came back in Maryland in that freak race (the Flirtation Stakes) in the mud, and we won by 19 lengths (laughing),” said Fuller. “He (Peter Fuller) always had high hopes for her. She sprinted a time, she broke the track record behind a very fast filly who did end up stretching out. That was the thing with her too. You win at five-eighths of a mile, setting very fast fractions too, obviously the big kahuna there with the Coaching Club American Oaks when it was still a mile-and-a-half. She certainly had plenty of naysayers, not of people that knew her, not so much necessarily horse people, maybe handicappers who thought they were smarter, and she just proved them wrong.”

However, it was the middle jewel in the Tiara that seemed to pose the greatest obstacle, the 1 1/8-miles Mother Goose Stakes (Gr. 1) had a uniqueness that brought with it its own series of challenges.

“And it’s funny that was almost an easier race (the Coaching Club American Oaks), the-mile-and-half because we had that first turn to rock into and slow down a little,” said Fuller. “With the Mother Goose (laugh) you’re way back in the chute, then you have the longest straightaway ever to leave the gate. I think it’s a mile-and-an-eighth. You’re going the longest mile-and-an-eighth. It’s kind of like the longest sprint ever. So, that was a tough one because she was relaxed a little bit more in the Coaching Club.”

Fuller and Mom’s Command formed what seemed to be a perfect partnership, understanding one another as they made their way toward racing history in an unforgettable sophomore campaign in 1985, one that would resonate for decades to come.

“Thank God, we pretty much fit,” said Fuller. “I was like. ‘Whoa baby, whoa mommy to her,’ with other guys shooting ducks and clucking and trying to get us to take off alongside. And then she would have that burst at the head of the stretch, another gear to kick away and adjust. It devastated the horses who would kind of run up to her like they thought they were going somewhere, and she kicked away. It was an amazing feeling too, to be on a horse like that.”

However, the race after the coronation of having won the Triple Tiara, had the appropriate name in a racetrack renowned for upstaging horses with stellar reputations, would end her winning streak at five. A Grade One sprint race at Saratoga would find Mom’s Command placing second to the filly that would win Horse of the Year honors in 1986, Lady’s Secret.

“And then of course, you go up in the Test, and it’s not called the Test for no reason, “said Fuller. ”But it was then jumping back to that much shorter distance between the Coaching Club and the Alabama. But the timing was perfect to have a race in there, and I’m certainly not going to say that The Test was a workout. But it wasn’t like okay we’re going to try to go the front in here too. She had learned to relax. They pressed me and pushed me over onto the fence, I scraped my boot and my stirrup, and I ended up backing her and coming around. It was really the only time she ever had to do that, but that did happen, and she came running. If that was further, she would have won that race. There was no disappointment other than we didn’t win.”

A short nine days later, Mom’s Command would close out her stellar career with a winning performance in the Grade One Alabama at the same upstate New York racetrack, punctuating an already amazing career that solidified her standing as the best of her generation.

“What a great race,” said Fuller. “And then of course, she won that. There was some talk, it’s the graveyard of champions. That was an amazing race. The Test was really a testament to her, and just to come back and really validate all of that in the Alabama.”

Center of Attention

And to the victor came the spoils. There’s nothing like winning a Grade One race at Saratoga, and Fuller’s victory in the Alabama left an indelible impression, showcasing the talent of a champion, and the significance the mount has had to the horsewoman’s career.

“It was fabulous,” said Fuller. “It was everything, the loudness of the spectators, seeing the different families faces who make up the crowd. It was a lot about this horse (Mom’s Command). This horse was special, and she really was. She was unique. She wasn’t lovey dovey. After a race, she would be chilled out. A lot of times I would get to graze her back at the barn after she had been cooled out. I’d hug her and pet her, and then her groom Teddy would go, ‘She’s mellowed out now!’ But she was a feisty girl. She was a big red-headed mama. She was big too. She was definitely all of 16.2 (hands) and well-built. “

It was shortly after Mom’s Command received the Eclipse Award that Fuller found out she was pregnant with her son Jorge.

Right on Time

It was a dark bay horse, out of the Dancer’s Image broodmare Dancing Memory and by the stallion Nearly on Time that gave Fuller her first stakes victory. But being the daughter of an owner, didn’t mean that Fuller was necessarily going to secure rides on her father’s horses. He had other ideas.

“Dad by no means didn’t put me on at the stable or anything like that, after I had won a few races,” said Fuller. “That’s not how it worked. It’s not what he believed in. He thought I should earn my way like anybody else. I feel like I did that. I think most people would agree who were around in New England at that time. That was cool. I’m glad. Maybe at the time, there were others that I wish they would’ve put me on. You have to have a little bit of that cocky confidence as a rider, going up and getting all those nos’, and then to finally get a yes.”

Fuller and Donna’s Time would score consecutive stakes wins during the colt’s juvenile campaign, winning the Miles Standish Stakes in November at Suffolk Downs, and following that race with a victory in the Allegheny Stakes at Keystone Race Track in the latter part of autumn. Donna’s Time would score four consecutive victories during his sophomore campaign, with wins in the Faneuil Handicap at Suffolk Downs and the Annapolis Handicap at Pimlico. He would later win the Wavering Monarch Stakes that summer at Monmouth Park. Donna’s Time was a horse that allowed Fuller to ride out of town.

“He was a neat little horse, not expensive, I think he toed-in, but he was a neat little runner,” said Fuller. “Ned is a great trainer, and he was able to pick out the individual way for certain horses, which he certainly did with a number of dad’s really nice horses.”

Back from the Breeding Shed

A Florida-bred chestnut horse by In Reality, with the same connections as Mom’s Command, Fuller’s Folly and Donna’s Time, owned and bred by Fuller and conditioned by Allard, would also provide Fuller with a couple of wins away from her New England base. Shananie was a horse, who when he retired, wasn’t well-received by breeders and returned to the racetrack, and when he did, he did so with an enthusiasm that at times produced profound results.

“Shananie was a great little horse, who had bowed and thought to be retired,” said Fuller. “He won the Engine One in New York (at Belmont Park as a 6-year-old), that had come off the turf.”

When Shananie went to Delaware Park in the fall of his 5-year-old campaign, Fuller was confident in the chestnut horse and that conviction and trust came from the way he performed on a challenging surface.

“He won the J.O. Tobin in Delaware too,” said Fuller. “I remember going into Delaware and they had a horse named Jeff who was very fast and had broken track records at 5 ½ furlongs. No one could beat him. I go into Delaware and a couple of the girls in the jocks room said, ‘Oh yeah, you better watch out for this turf course, it’s pretty bumpy.’ And my little horse Shananie had run at Suffolk, we used to laugh, it was the roller coaster. We said with the tides, the different low spots would change a little. Rockingham was a very different turf course. It was flat and smooth, and it was quote-unquote all-weather where it drained really well. Suffolk was old school, was near the water and the marsh, so I definitely think those tides affected it. A horse had to be really game and pretty darn talented.

“I saw a number of horses that went out of town including Fuller’s Folly and Shananie both for dad, and Greida and Jacuzzi Boogie, they were all nice turf horses in New England, and absolutely went out of town and held their own at the same or better level because they got tested over there. Also, it was good competition. Delaware, that was nothing for Shananie. He smoked them.”

More Stakes Wins

A gray filly by Far North, out of the Restless Native mare Kiss the Clown, also brought Fuller added money luck during the late 1980s. Ned Allard conditioned the two-time stakes winner, who won the Pinafore Stakes at Suffolk Downs and the Medieval Moon Stakes at The Meadowlands.

“Greida, she was wonderful.,” said Fuller. “Dad really did some excellent breeding. Not huge money, but he certainly looked for those nice mares with pedigrees, some he had gotten out of New York and different places.”

Backside Support

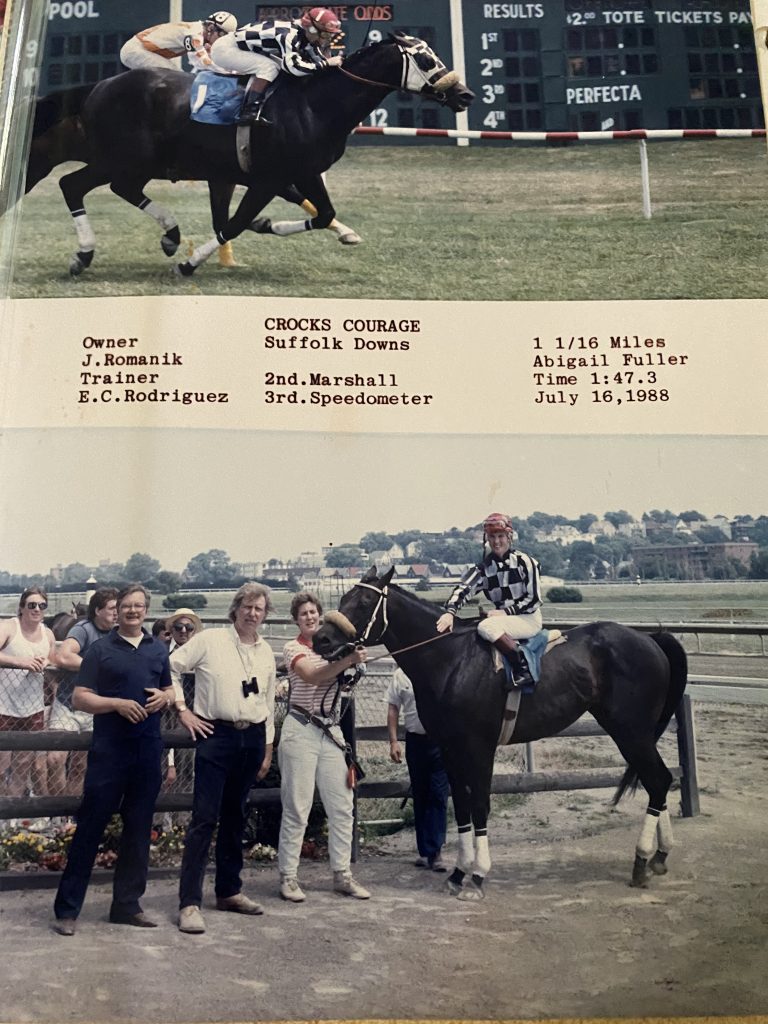

Fuller was fortunate that she was able to ride for a lot of good horsemen in New England, who played a significant role in her success. One was a former jockey who had emigrated from Cuba. Fuller had ridden for this particular conditioner when she was an apprentice and after losing the bug, and then after she had her son and returned to the races.

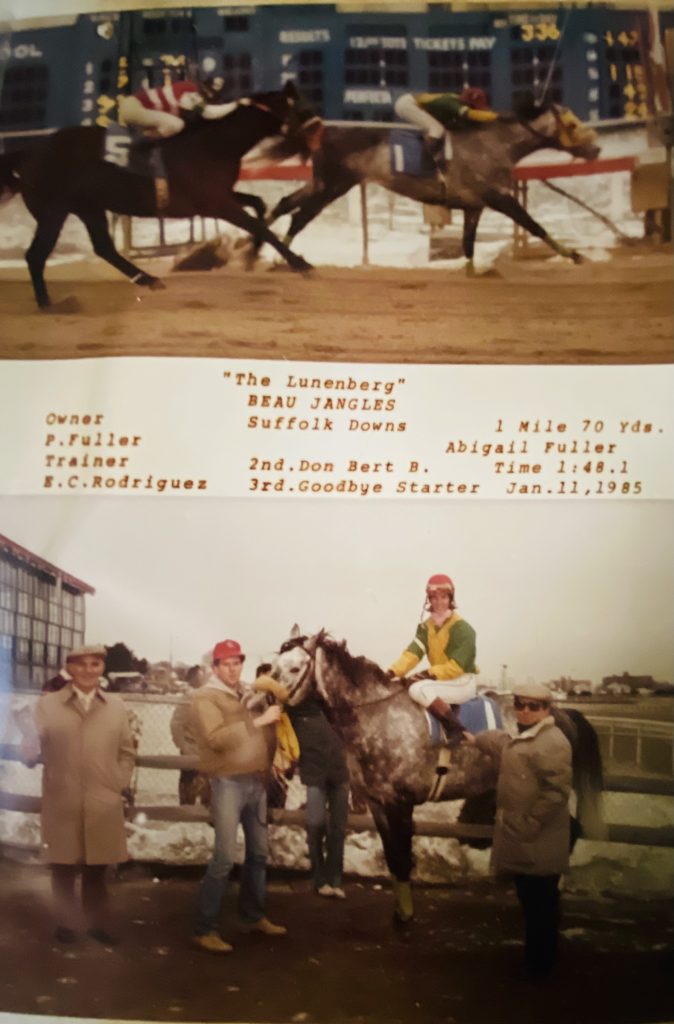

“Emilio Rodriguez was just a super horseman and super friend, and he also taught me a lot,” said Fuller. “He didn’t have a huge stable. His horses were always runners. In addition to Ned Allard, I was able to ride for some of the old-time people, Bruce Smith and Floyd Duncan who were really good horsemen.”

No Laughing Matter

A chestnut gelding by the 1978 Triple Crown winner Affirmed conditioned by Ned Allard and bred and owned by Peter Fuller would result in a couple stakes wins for the jockey who was now also a mother. Fuller’s Folly, who like Mom’s Command, was also out of a Pia Star broodmare, Fashion Star. The rider and horse were a serious combination, not one to be trifled with as the competition soon found out.

“Fuller’s Folly almost won the New Hampshire Sweepstakes (Gr. 3), but he got blocked, somebody let their horse lazily drop over in front of him, and when they should have stayed where they were,” said Fuller. ”He was a big long striding horse, late striding horse. So, he didn’t win. He kind of got checked, but this horse was moving.”

However, the eighth-place finish in the added money race at Rockingham served as the perfect prep 11 days later for a route tilt, the 1 5/8-mile Grade Three Seneca Handicap at Saratoga, that is if the weather cooperated.

“It rained all day, and this horse would not run a jump on the dirt,” said Fuller. ”He trained fine and stuff, but he didn’t want to run on the dirt. We just prayed all day, please let it stay on the grass. It was soggy almost like a pig field, he didn’t care as long as there was grass on there. El Senor was in the race. He made that late move, not too late, I think El Senor was actually behind us. We got up. The Seneca worked out pretty well. It was wonderful. The picture is kind of a riot. The sky is black and gray behind us and we’re standing out in the mud tracks in the photo. But he got it done.”

Breakfast is Served

A horse owned by Fuller’s Godfather, who she referred to as Dr. Johnny, would also bring her stakes winning success. The Massachusetts-bred gelding campaigned by John Costello and trained by Ned Allard, by Shananie, out of the Blade mare Native Blade, was also among the stakes winners ridden by Fuller during her career. The horse was named after a popular breakfast staple, said Fuller.

“My Godfather was John Costello, and my father brought him into the game,” said Fuller. It was Costello and Peter Fuller that helped bring Stonehedge Farm’s Gil Campbell into the game. “Scrambies, Donna’s Time and Attention Amy, they were all there with those guys. Scrambies or scrambled eggs was Dr. Johnny’s favorite breakfast food. He also had Jacuzzi Boogie, who was a wonderful and beautiful mare, kind of related to Mom’s Command in a two-thirds way. Dad, he was really good with the pedigrees. I remember the horses from back in the day, but the pedigrees he was really good with. We had a lot of fun and it was kind of amazing to get to do it,”

Love and Marriage

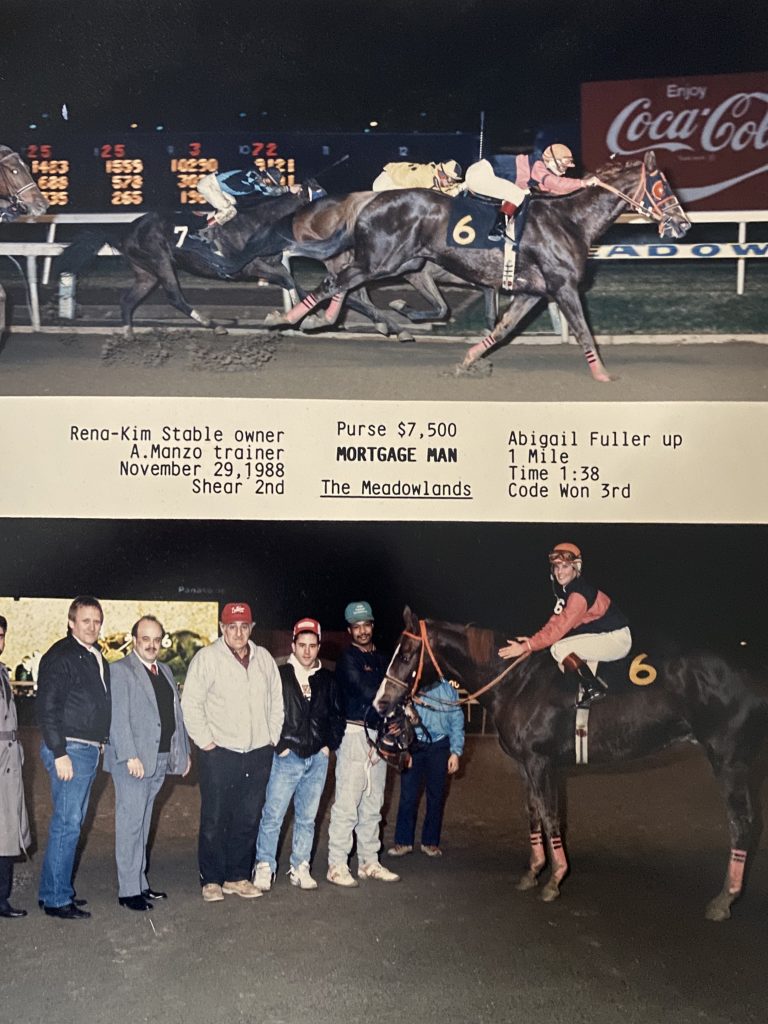

Fuller and her former husband Mike Catalano would form a formidable combination, providing her with an opportunity to ride a number of quality horses.

“We got together, and he had a pretty sizable stable in New England, probably about 30 horses,” said Fuller. “He was a really good up-and-coming young trainer, and I rode a lot of those horses, not all of them, but I did gallop a lot of them as well. So, it was different, instead of hustling around to different barns I got to be connected with a number of horses as much as you can with a claiming stable. That’s its own game and it was different. But we were able to work together as a team and had some nice owners. That was the difference. I’m galloping six to eight a day, like back in the old days and riding too.”

Paddocks and Publicity

A propitious opportunity would come Fuller’s way, and find her behind the microphone, providing handicapping analysis, as a track analyst, after sustaining an injury to her back. Her insight as a jockey gave a greater perspective to the in-house presentation at Suffolk Downs.

“They gave me a job in the paddock,” said Fuller. “I did the picks before the races, and some handicapping seminars. Chip Tuttle and Ted Nicholson and Mr. James Mosely, they gave me a chance. I had a broken the T2 (vertebrae) in my back. I didn’t ride for five or six years. I did gallop, but I thought I was done racing.”

Fuller would return to actively riding as a journeyman, but she was able to retain her position as part of the broadcast team.

“And then I came back while I had that other job,” said Fuller. “They allowed me to. if I rode the last race or two for Mike, or the first race or two, the other part of the day I worked in the paddock. So, it was really fun. I worked for publicity basically. They were happy to have me, and I was happy to do it. It was through some really great years, until 1999.”

Staying Busy

Among the horses’ Fuller rode for Catalano was a chestnut son of Tejano named Harlan County, and the combination would win the Suffolk Downs Speed Stakes. Arthur Cort campaigned Harlan County. She also enjoyed success with the Robert Gonsalves conditioned Cousin Kelly, winning the First Episode Stakes at in the spring of 1997, capturing the 1 1/6-mile contest by 4 ½ lengths.

Paul Bonaventura was another horseman who Fuller enjoyed success with during the 1990s.

“After coming back, even riding for Mike mostly, I had a few people that I really rode regularly for and they trusted me, Paul being one of them, I didn’t have to run around hustling mounts,” said Fuller. “It was really cool.”

New Surroundings

An opportunity to leave the harsh New England winters, and head to sunny Florida would eventually become a reality for Fuller and Catalano, but they would try another circuit before eventually making their way south.

”We spent one year in New York,” said Fuller. “Mike tried it, it didn’t really work out, so we came to Florida. And I decided I’m done, I didn’t ride a lot in New York that year we were there, he had a small stable, I kind of regrouped, ‘I had a great career, I’m done.’”

Condition Books, Cuts on the Clipboard and the Claiming Box

Once again, Fuller found her career evolving, but she would remain involved with the Thoroughbred industry, this time hanging her own shingle outside of the barn.

”It was during the early 2000s, Mike went out and did real estate, so I took out my trainer’s license, and trained for probably a year-and-a-half,” said Fuller. “I liked it, but to be honest, I liked race riding more. Training’s tough, it’s not for the faint of heart, especially if you have claiming horses or anything like that. It’s not easy, I did enjoy it of course. I trained some for dad, so that was awesome, and for a few New England people. I always had very good clients. Dad was definitely cutting back his stable at that time. I did like it, but it was not something I ever said, ‘Gosh, I have to do this for the rest of my life.’ It was fun.”

Back in the Saddle

But one should never say never, as Fuller would find herself returning to the saddle once again, riding another one of her father’s horses, but this time it was a horse Fuller was extremely familiar with, and was in the charge of people she knew well.

“Another filly of dad’s; that little wild red-haired girl, some other trainers really didn’t want her because she was tough,’ said Fuller. “But Ronnie Gaffney and Emmy Gaffney kind of took us under their wing, we were with them. I galloped her and groomed her and then the jock got hurt, and I said to my dad, my son and to Emmy and Ronnie, ‘I should ride her because I got on her every day.’ A.J.’s Hot Mambo. She actually a half-sister to a stake mare, who Gail Wolfson had. A.J.’s Hot Mambo, the one I had, she was a cheap filly, who I think we broke her maiden for $20,000. They all said, ‘You should ride her.’ So, I did, and I think she paid about 40 bucks at Calder in the summer or fall in 2011. She won, and that was the first one back in 10 or so years.”

It provided Fuller with the opportunity to ride at the Hallandale Beach, Fla.-based racetrack, something she hadn’t done previously because she had spent the preponderance of her career riding in the northeast.

“So, then I rode that season through,” said Fuller. “I had never ridden at Gulfstream. I had always spent the winters in New England. So, Ronnie kind of encouraged me, he was like, ‘Come on.’ He didn’t have a big stable, but I got to win a race for them at Gulfstream in January, so that was really cool. I beat Johnny V and Pletcher on a horse owned by Scott Savin, we came down head-and-head in the stretch. He was a beautiful dark brown horse.”

Lady Legends

An opportunity to take part in history with several of thoroughbred racing’s pioneers, allowed Fuller to interact with those female jockeys that came before her and her contemporaries who helped change the sport in a competitive environment and in a unique platform that was well-received and embraced warmly by the audience.

“I did have the opportunity to ride in those lady legend races,” said Fuller. “That was actually when I got to meet Barbara Jo Rubin and I had already met Diane Crump, actually when she rode again when she was a trainer, and it was a thrill to meet her. She was just really cool and gracious. Then to be there. She came to that race, Kathy Kusner came but they didn’t ride. But Barbara Jo did which was amazing, I also had the opportunity to meet Mary Russ. I knew of her because she was the first woman to win a Grade One with Lord Darnley on the turf (the Widener Handicap at Hialeah). It was great to be able to ride with them. and (Patti) Cooksey was there. What a fun opportunity that was in Maryland (at Pimlico).”

Racetrack Representative

Her expertise, professional and life experience kept her in good stead, and Fuller was the perfect ambassador for a role she played at one of the nation’s premier racetracks.

“Gulfstream was fun, and I really did enjoy teaching people about racing and horses,” said Fuller. “We had the Saturday breakfasts in the winter. We had a lot of people who were curious and had some great questions and it was such a pleasure to, they were like, ‘you’ve got the real inside scoop.’ And I’m like ‘Yeah, I really do.’ So, I did really enjoy that.”

Balancing Racing and Family

Fuller went back to riding at the racetrack about a year after her son, Jorge Fuller-Vargas, who is a jockey, was born. She was fortunate that her sister Jessy, and two great friends who happened to be sisters, Cindy and Debbie, would watch her son, while she plied her trade as a journeyman at the races.

“Rockingham, when he got a little bigger, actually had a daycare,” said Fuller. “He used to go there, and there were a lot of little kids, and it was great, you would get done in the morning and say hi to all the kids, and then go ride your races and that was really cool.”

When Fuller broke her back, the T2 vertebrae, her son Jorge was about three and was becoming nervous, said Fuller.

“When I came back, I probably rushed it just a little bit,” said Fuller. “I think both of us had some nerves (laughing). I won a race for some really good friend Denise and Rollie Hopkins. And then I said, ‘I’m just going to gallop for a while.’”

The self-imposed retirement lasted five years, until her daughter Marisa was born in 1995. Her mother in-law, Sis Catalano, played a critical role in helping with the children, who Fuller describes as amazing and was her right hand, joining her son and daughter in-law at Delaware Park, as they plied their trade.

“Mike (Catalano, Fuller’s then husband) had brought his stable to Delaware for the summer,” said Fuller. “Marisa was probably along for a ride or two when I was exercising horses, but not in a race. And then, five years after I had Micayla in 2000. They were around and they used to come to the track. They could ride the walking machine. We had little ropes set up where they could hang on and play, probably the most at Delaware (Park).”

At The Meadowlands in 1999, Fuller won a race knowing she was pregnant with Micayla, but it was during the contest that an apprentice rider almost dropped her, with the horse stumbling, and with everyone’s heart skipping a beat.

“Mike was like, ‘That’s it, no more racing until after the child is born,’” said Fuller. “So, then I did ride a little bit in New York, and then we came to Florida and I just galloped from then until Calder in 2011.”

Having children didn’t impact her career, but it changed it as Fuller was riding more horses that she knew, worked with and galloped every day, which was different from the beginning of her career.

“I honestly enjoyed both phases equally,” said Fuller. “It was really neat to be able to work with a horse, gallop it every day and have it really come around, and then be able to ride it. Mike claimed a lot of horses too. So, they were in and out of the barn a lot. But he did have some horses for my dad and other people who bred their own.”

Full Circle

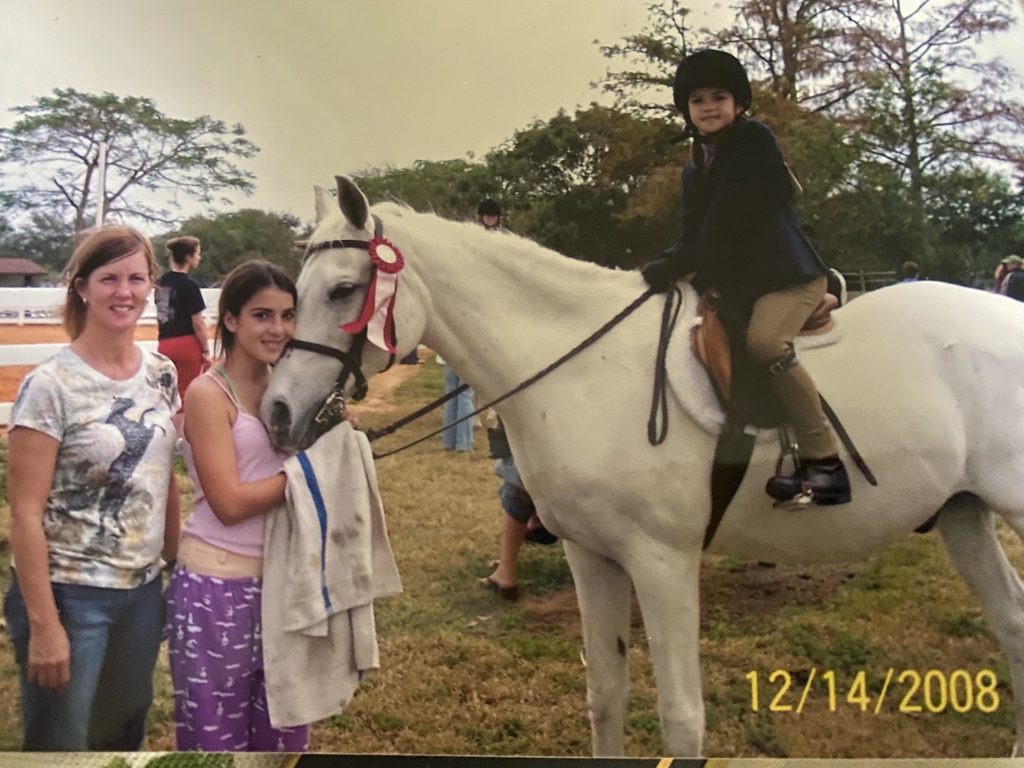

Ocala presents a host of new opportunities for Fuller, who is getting back to her roots as a horsewoman. The depth of Fuller’s horsemanship includes equine psychotherapy and therapeutic riding, allowing her to make a successful transition. Her farm is named Full Circle.

“I hope to be able to expand that more up here in Ocala,” said Fuller. “I’m not quite sure how that will look. There’s certainly plenty of horses, and plenty of people that get that kind of work. Kids, foster kids, teaching them leadership skills. Horses have so much to offer us. It’s kind of coming back to that full circle about what can the horses teach us. On the ground learning about communicating with the horse, just through energy. I’m thrilled.”