Jimmy Winkfield on Pentacost

On Monday, May 17, 1875, before a crowd of 10,000 fifteen 3-year-old colts lined up to compete in the inaugural Kentucky Derby. Thirteen of the fifteen jockeys who would pilot these colts in the 1 1/2 mile contest were African Americans.

The winner would be Aristides by two lengths in a time of 2:37.75, a world record for the distance at the time. His jockey was Oliver Lewis, his trainer was Ansel Williamson, and his owner was H.P. McGrath. Aristides’ half-brother and stablemate Chesapeake also ran in the race. Both Aristides’ jockey and trainer were black.

Blacks dominated racing in the late 1800s, winning 15 of the first 28 Derbies according to BlackAmericaWeb.com and training six of the first 17 winners. By the early 1900s, however, blacks had been pushed out of the business, which had also become wealthier and less accessible to the working classes. Black jockey James Winkfield won the Kentucky Derby in 1901 and 1902, but after 1921 there were no black riders in the race until Marlon St. Julien in 2000.

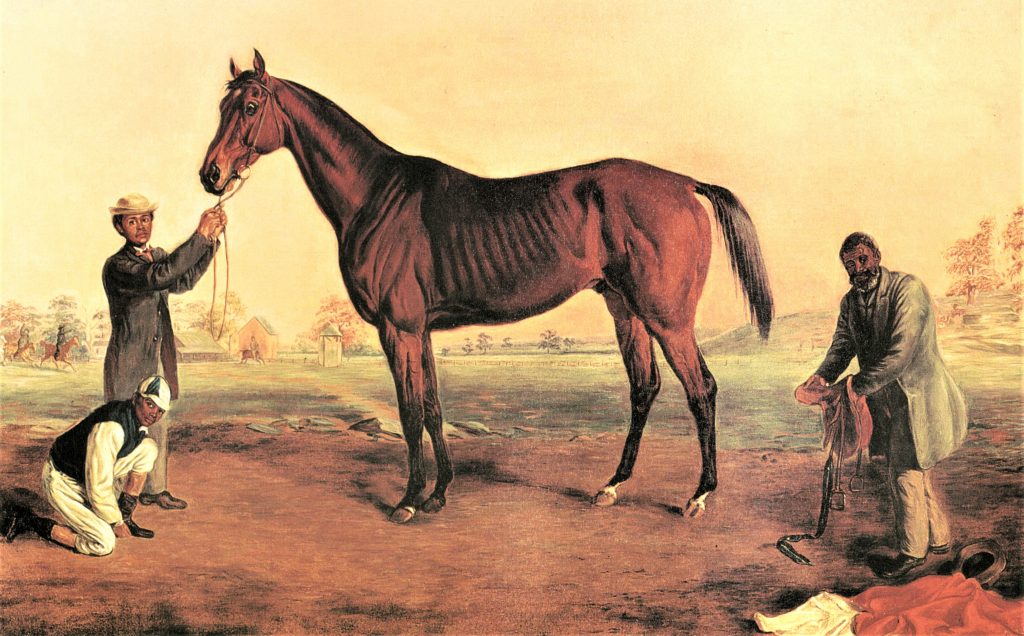

Ansel Williamson was born a slave in Virginia sometime around the mid-19th century. In 1864 he was purchased by Robert A. Alexander, owner of the famous Woodburn Stud near Midway, Kentucky. He was taught the breeding and training of horses and after he was given his freedom Williamson remained in Alexander’s employ. He conditioned a number of successful horses including the undefeated U.S. champion three-year-old male, Norfolk and the undefeated Asteroid.

Williamson trained R. A. Alexander’s Merrill when he won the third edition of Travers Stakes in 1866 and, also the 1866 Jersey Derby. Williamson would win both prestigious races again in 1873 with Henry Price McGrath’s Tom Bowling, a colt whose record would stand at 14 wins of his 17 career starts with two second places many of which were stakes.

Following Robert Alexander’s death in 1867, Williamson went on to train many great horses including Virgil who was the sire of the great Hindoo. Best remembered for having trained Aristides, the winner of the inaugural Kentucky Derby in 1875, his horse Calvin won the Belmont Stakes that same year. In addition, Williamson trained horses who won other major races such as the Jerome Handicap and the Withers Stakes.

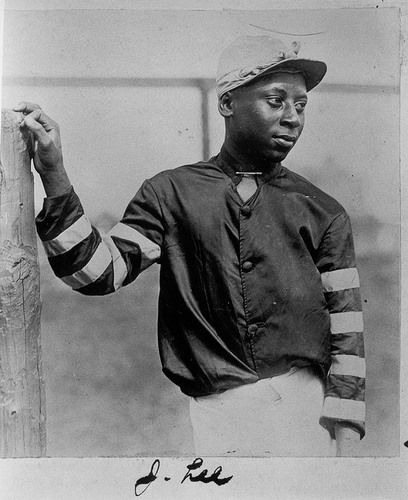

Oliver Lewis

Oliver Lewis was born in 1856 in Fayette County, Kentucky; his parents were Goodson and Eleanor Lewis. Very little is known about Lewis’s life, but according to the Black Athlete Web site he was “A family man, a husband and father of six children.” Lewis was 19 years old in 1875 when he entered the inaugural Kentucky Derby.

In addition to winning the first Kentucky Derby and setting a new American record time for a mile-and-a-half race, Lewis and Aristides took second place in the Belmont Stakes.

Lewis’s career as a jockey did not last long. After a spell working as a day laborer Lewis began providing notes on racing form to bookmakers and later became a bookmaker himself, a profession that was then legal in the United States. Lewis’s methods of collecting data and compiling detailed handicapping charts have been likened to the systems used by the Daily Racing Form. Lewis passed on his bookmaking skills and business to his son James.

Despite his role in the history of one of America’s most famous sporting events, Lewis has been neglected by sportswriters for well over a century and his life beyond the famous race is practically undocumented.

After his death in Lexington in 1924 he was buried in Lexington Benevolent Society No. 2 Cemetery, now known as African Cemetery No. 2, along with several other black jockeys of the period, including Isaac Murphy, who won the Derby three times.

On September 8, 2010 the Newtown Pike Extension in Lexington, Kentucky was named Oliver Lewis Way in honor of Lewis’s historic accomplishments.

William Walker

Born a slave in near Versailles, Kentucky, William Walker was the leading rider at Churchill Downs in the fall racing season of 1875-76 and the spring campaigns of 1876 through 1878.

In 1877, Walker rode Ten Broeck, whose trainer, Harry Colston, was also black, in the Great Baltimore Sweepstakes match race against Parole and 1875 Preakness winner Tom Ochiltree at Pimlico Race Course. The three jockeys and horses are immortalized on the side of Pimlico in bas relief. Walker was the unfortunate third place finisher in the historic race attended by Congress.

Walker was the winning rider aboard Ten Broeck in a famous July 4, 1878, match race at Louisville, Kentucky, against the great California mare, Mollie McCarty.

For owner Dan Swigert and future U.S. Racing Hall of Fame trainer Edward D. Brown, he rode Baden-Baden to victory in the 1877 Kentucky Derby. Walker made his fourth and final appearance in the 1896 Derby, finishing seventh. He retired that year but stayed in horse racing as a trainer and as an adviser to renowned breeder, John E. Madden.

Billy Walker died in September 20, 1933 and was buried at the Louisville Cemetery at the corner of Eastern Parkway and Poplar Level Road. During the 1996 Kentucky Derby Week, Churchill Downs erected a headstone on his previously unmarked grave with an epitaph outlining his career.

Isaac Murphy

Isaac Burns Murphy was born in Fayette County, Kentucky to parents who were not enslaved. His father, James Burns, joined the Union Army and died during his military service. Isaac was only a toddler at the time.

Isaac’s mother moved back to her father’s house in Lexington, Kentucky, and began working as a laundress to provide for her children. She sometimes took Isaac with her and by fate one of her customers owned a racing stable. Isaac made himself useful by cleaning stalls and exercising horses. Eli Jordon, the black trainer at the stable, noticed the young boy’s natural ability and occasionally let Isaac help with breaking the yearlings.

Jordon also admired Isaac’s self-discipline and good humor. In 1875, he decided to put the 14-year-old boy in his first race. One year later, Isaac Burns had become the jockey to watch. His grandfather, Green Murphy, had been a loving figure in Isaac’s life so when Isaac began racing, he chose to take his grandfather’s surname.

In 1887, Murphy commanded $12,000 just for “first call.” He also was paid for second and third call availability. By 1887 Murphy was thought to be the highest paid athlete in the U.S.

Murphy married Lucy Osborn and purchased a large home in Lexington (the purchase of which was noted in The New York Times, 6-13-1887). He began living the good life in the post-Civil War south.

In 1890, Murphy won the Suburban Handicap at Sheepshead Bay on Salvator over a horse named Tenny. Tenny was ridden by his white counterpart, Snapper Garrison, equally famous and also highly-regarded. Salvator won decisively but Tenny’s owner complained that there had been interference and insisted on a rematch. The match race was scheduled at Sheepshead Bay for June 25, 1890.

Interest in the race was high. The press pitched the race of “black vs. white.” Snapper Garrison was a big, lanky white jockey who rode in a high crouch position and favored the whip when he wanted a big finish. From the grandstand, it was easy to tell the riders apart as Murphy’s upright seat was in stark contrast to Garrison’s crouch.

Mounted on Salvator, Murphy opened a big lead on Tenny but twice Tenny gained on closing the gap. Down the stretch Murphy had a two-length lead as Garrison moved Tenny within a head of Salvator. At the finish it was Murphy and Salvator who would prevail as the winners.

This race might have been fought over, too, but as fate would again have it, a photographer was at the finish. The photograph marked the first-ever “photo finish,” and after the film was developed, it confirmed Salvator was the winner by a nose.

Salvator-Tenny Match Race

Shortly after the Salvator-Tenny match race, Murphy would encounter difficulties. Riding at Monmouth Park in New Jersey, he came in dead last on the favorite Firenzi and then fell off. Assuming Murphy may have been drinking Monmouth suspended him for the remainder of the season. However, the spectators held Murphy in such high regard recognizing this was so uncharacteristic of the serious-minded, disciplined jockey that there were no comments or hissing from the grandstand, only respectful silence. Murphy’s defenders pointed out that with crash dieting to make weight, most jockeys had low tolerance for alcohol.

In 1891, a better year, Murphy rode in 100 races and won the Kentucky Derby on Kingman with a win rate for the year was 28 percent. However, in successive years he rode less and less, and the horses offered him were no longer the top flight ones he was used to. In 1894 he had another suspension at Latonia in Kentucky.

Isaac Murphy was one of the great jockeys in Thoroughbred racing. He was the first black jockey to be inducted into the National Museum of Racing Hall of Fame. Among his many credits were three wins at the Kentucky Derby and four wins at Chicago’s American Derby at Washington Park Race Track, the most prestigious track in the late 1800s.

By his own calculation, Isaac Murphy won 44 percent of his races. More recent statisticians who have studied his races report that his percentage was more likely 34 percent — 530 wins and 1538 rides. An admirable record by either standard.

Isaac Murphy’s last race was on the track at Lexington in November of 1895 on a horse named Tupto. He died of pneumonia on February 12, 1896 just a few months after this race.

Isaac Murphy was so well-known that his funeral was covered in The New York Times (11-18-1896): “The largest funeral ever seen here over a colored person was held on Sunday when Isaac Murphy, the famous jockey, was buried. The services took place at his late home on East Third Street. The body was escorted from the house to the cemetery by Bethany Commandery, Knights of Templars and the colored lodges of Masons. The funeral procession was one of the longest ever seen in Lexington. A number of prominent turfmen from all over the country were present, and floral tributes were sent from nearly everywhere; it requiring a large wagon to haul the flowers that the dead jockey’s admirers had sent to decorate his grave. The remains were buried in the colored cemetery on Seventh Street.”

Isaac Murphy had imagined an epitaph for himself: “I am as proud of my calling as I am of my record, and I believe my life will be recorded as a success, though the reputation I enjoyed was earned in the stable and saddle. It’s a great honor to be classed as one of America’s great jockeys.”

Instead—even after all the pomp and circumstance–Murphy was buried in an unremarkable grave.

Frank Borries Jr., who worked at the University of Kentucky in the 1960s, went out to look for Isaac Murphy’s grave one day. He discovered it was no longer marked. For the next three years, Borries worked to identify which plot held Murphy, and once he did so, he worked out reburial. Isaac Murphy was re-interred in 1967 at the burial site of the famous race horse, Man o’ War.

Then in the 1970s plans for a new Kentucky Horse Park were made, and the plans specified honorary placement for both Man o’ War and Murphy. In 1978 when the Park opened, Man o’War and Isaac Murphy were both relocated to a plot of land at the entrance to the Park.

Since 1995 the National Turf Writers Association has remembered Murphy by presenting the Isaac Murphy Award to the North American jockey with the highest winning percentage for the year.

Alonzo Clayton

Alonzo “Lonnie” Clayton was born in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1876, one of the nine children of Robert and Evaline Clayton. At age ten, his family moved to North Little Rock, Arkansas, where he attended school and worked as a gofer for a hotel and as a shoeshine boy to help support his family.

Three years later the diminutive Clayton left home heading north to Chicago’s prestigious Washington Park Race Track where his brother Albertus was a jockey for prominent Thoroughbred horse racing stable owner, Lucky Baldwin. Lonnie was given a job as a stablehand and exercise rider for the Baldwin stable. The following year Clayton moved east to the Clifton Race Track in New Jersey where in 1890 at fourteen years old he began his professional riding career.

Clayton won big stakes races early in his career. In 1891 at Morris Park Racetrack in The Bronx, New York, he won the Champagne Stakes aboard Bashford Manor Stable’s Azra. On May 11, 1892, he rode Azra to victory in the Kentucky Derby becoming the youngest jockey in history to ever win the Derby at age fifteen. Clayton and Azra followed up their Derby success with victories in the Clark Handicap and the Travers Stakes.

At Monmouth Park in New Jersey Clayton won the 1893 Monmouth Handicap and went on to win the fall riding title at Churchill Downs. One of the leading money winners on the East Coast racing circuit during the 1890s, he won races from New York to California. Lonnie Clayton captured back-to-back runnings of the Kentucky Oaks in 1894 and 1895, the latter a year in which he won 144 races and finished in the money sixty percent of the time. In 1895 he won the Arkansas Derby and in 1896 finished third in the Preakness Stakes aboard the filly, Intermission. Clayton was one of the most successful jockeys in America at the age of 20.

However, by the start of the 20th century, racism became an issue in America and opportunities to ride soon vanished as stable owners switched to using white riders only. Within a few years, African-American jockeys, who had dominated racing and who had played a major role in bringing Thoroughbred racing to the forefront of American sport, were forced out of the business. Since 1909, no African-American jockey has ridden a winner in any major American Graded stakes race.

Lonnie Clayton’s success had allowed him to acquire a property in his family’s home of Little Rock where in 1895 he built a Queen Anne-style home. An astute businessman, in 1897 Clayton also built a commercial building on Main Street in Little Rock, which stood until about 1980. However, denied the right to earn a living in racing in America, he was forced to sell his investment property and his home. His North Side residence is today known as Engelberger House and since 1990 has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Clayton lived his last few years in California where he worked as a hotel bellhop. He died at age forty on March 17, 1917, of chronic pulmonary tuberculosis. He is buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Los Angeles.

Alonzo Clayton’s accomplishments in racing were recognized by the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame with his induction in 2012.

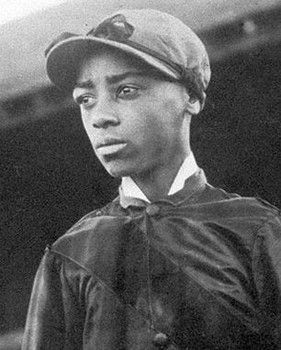

Jimmy Winkfield

Jimmy Winkfield was on the doorstep of becoming America’s greatest black race rider. One of just five men to win back-to-back Kentucky Derbys (1901-1902), he barely missed a third victory the following year. But, the story of James “Wink” Winkfield being a great jockey would just be a chapter of his story.

Born in Chilesburg, Ky. in 1880, Winkfield was the youngest of 17 children in a family of sharecroppers. The son of a slave, as a youngster Winkfield split his time between daily chores on the farm and eyeing the strings of Thoroughbreds that paraded down the farm’s dusty lane. He studied the ways of gifted horsemen by watching through the fences that lined the Bluegrass horse country.

Winkfield dreamed of becoming a jockey and following in the footsteps of prominent black riders like Isaac Murphy. At age 15, Winkfield left the farm to work as a stable hand at Latonia Racetrack, and progressed to exercising horses. He earned $8 a month and board. “I was rich,” he later boasted.

Winkfield had his first call to post aboard Jockey Joe at Chicago’s Hawthorne Racetrack with disastrous results. Peter Chew vividly described the race in his book, “The Kentucky Derby: The First Hundred Years”: “Breaking fourth from the rail, he cut straight across the path of three inside, trying to get to the rail — and all four horses went down. The stewards put Winkfield down too, for a year.”

Winkfield had four appearances in the Kentucky Derby. In 1900 aboard Thrive (Top Gallant {GB}) for owner-trainer Julius C. Cahn he finished third. Returning in 1901, piloting Frank B. Van Meter’s His Eminence (Falsetto) to his first Derby victory. With the call aboard Thomas Clay McDowell’s Alan-a-Dale (Halma) Winkfield repeated the feat in 1902.

In the 1903 edition Winkfield rode Early (Troubadour) trained by Patrick Dunne and owned by Myron H. Tichenor & Co. finishing second by three-quarters of a length. No jockey has topped his Derby record of two wins, a second and third place.

Winkfield was a cocky and daring rider who was very much in demand and just 21.

Then, an unwise decision would changed his life dramatically. Winkfield broke a verbal commitment made to John Madden, agreeing to ride the horse of another man and in the same race in which he was to ride for Madden. Madden, the well-known powerful Thoroughbred owner, swore that the jockey would not in New York. The opportunities for black riders in other parts of the country was limited as race riding was becoming almost exclusively for whites.

In the early 1900s, a combination of big money, violence by white jockeys, even intimidation from the Ku Klux Klan was forcing the great African-American jockeys from the racing game. A professional jockey for just five years, Winkfield bought a steamer ticket when an offer came to ride in Czarist Russia. Winkfield travelled to Europe and went on to Russia with nothing but a Russian/Polish/English dictionary in late 1903.

European noblemen and wealthy oil barons owned top-tier horses that competed at Moscow and St. Petersburg racetracks. Wink won the multiple editions of the Moscow Derby, including aboard four-time victor Bahadur, and competed with great success in Austria and Germany over the years.

Earning a king’s ransom, $100,000 annually, Wink purchased a suite in Moscow’s luxurious National Hotel, where he employed a white valet. He ate caviar for breakfast and drank vintage bottles of wine with a circle of friends that included millionaires and aristocrats in Czar Nicholas II’s court.

Winkfield regularly rode winners in Russia, Poland, France, Austria, Hungary, England, Spain, and Italy, ultimately winning nearly every marquee race on the continent. He was celebrated in the sports pages, and the gossip pages, too.

Winkfield’s high life didn’t last. By 1917, the Bolsheviks and the Communists had risen to power and racing was shuttered. Winkfield and his racing community moved to Odessa on the Black Sea but were soon after forced to flee.

Winkfield helped lead 250 Thoroughbreds, Polish noblemen and horsemen across the Transylvania Alps to Poland. Robbed by the villagers and with no food during the three-month nightmarish odyssey they survived by eating some of the horses. The bloodlines of some greatest stallions in Europe can be traced back to horses Winkfield saved.

After again restarting his riding career in Poland, a former Russian patron brought Winkfield to France in 1922. There Winkfield married his third wife, Lydia de Minkiwitz, a Russian baroness, and

his father-in-law presented the newlyweds with a three-story chateau and private stables in the lush countryside outside Paris.

Winkfield resurrected his career in France and launched a racing stable in the historic town of Maisons-Laffitte, 11 miles outside of Paris. He spoke French fluently, became a bon vivant of the Paris racing scene sharing the limelight with the likes of Ernest Hemingway, Josephine Baker, and royalty from around the world.

But by age 48, the physical toll of riding forced him to retire. With year’s of horsemen’s knowledge under his belt Winkfield began a successful training career in 1930. A decade later, when Adolph Hitler’s troops invaded France and the Nazis stormed the property in 1941, Winkfield defended himself with a pitchfork. They requisitioned all his horses, stables and house. Winkfield fled once more, this time back to America.

Hardly anyone knew or cared about Winkfield’s racing history back there. The only job he could get in racing was as a groom. Disgusted with the second-class status of blacks and in racing, he returned to Maisons-Laffitte in 1953. Winkfield would go on to operate one of the most successful racing stables in France through the 1950s and 1960s.

In May 1961, Winkfield returned to the United States to attend the Kentucky Derby for the first time since 1903. Winkfield and his daughter Liliane were invited to a reception to honor the two-time winner hosted by Sports Illustrated at the luxurious Brown Hotel in Louisville, Ky.

Because America was still segregated, the black doorman wouldn’t allow Winkfield, the guest of honor, to enter through the front door. Winkfield stood his ground and eventually was admitted. Sadly, the banquet guests ignored Wink and his daughter. Except for one — Roscoe Goose — a white jockey, who had won the 1913 Derby on Donerail, who at 91-1 was the longest price winner in Derby history. Goose recognized Winkfield and sat at his table. Three days later they met again on Derby day. True to style, Wink was dressed in a dapper, pin-striped suit and sported a Fedora. The two Derby winners smoked cigars and told stories to the hometown reporters.

When Winkfield had earned enough money, he travelled back to Maisons-Laffitte. In his later years, he walked painfully with the aid of two canes, exerting a body that had lived an amazing 92 years. He passed away on March 23, 1974, and was buried in the town cemetery.

Thirty years after Winkfield died he received his due. He was inducted into the U.S. Racing Hall of Fame, its third African-American jockey. The award was presented to his daughter Liliane Winkfield Casey. Every year, Aqueduct stages the six-furlong Jimmy Winkfield Stakes on the third Monday of January, Martin Luther King Day — a fitting tribute to the last black jockey to win the Kentucky Derby.

These are just a few of the African Americans who were the foundation of American Thoroughbred horse racing. We honor their immeasurable contributions.

For more information about African American jockeys, see the Facebook page maintained by Project to Preserve African American Turf History.

MbKalinich

Photos:

Jimmy Winkfield on Pentacost. Credit: Keeneland Library Cook Collection

Asteroid with Ansel Williamson (right). Credit: The Keeneland Library

Oliver Lewis. Credit: Public domain

Oliver Lewis on Kentucky Derby winner Aristides. Credit: Kentucky Derby Museum

Isaac Murphy. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Salvator-Tenny match race. Credit: The Keeneland Library Hemment Collection

Alonzo “Lonnie” Clayton. Credit: The Keeneland Library

Jimmy Winkfield. Credit: Keeneland Library Cook Collection

Jimmy Winkfield aboard 1902 Kentucky Derby victor Alan-a-Dale. Credit: Kentucky Derby Museum